This CHP officer sought sex from women who needed his help inspecting their cars, records show

Nicole remembers feeling grateful that Officer Morgan McGrew agreed to meet her so early in the morning. The 7:30 a.m. appointment would let her verify her car’s vehicle identification number and still make it to work on time.

But when she met McGrew in the parking lot of the West Valley California Highway Patrol Office in Woodland Hills, the officer said he was having trouble finding the VIN sticker on her car door. Then the conversation abruptly shifted.

“‘I’ll pass this car, and you’ll be able to get your registration, if you go out on a date with me,’” she remembers McGrew saying. “I kind of froze,” she says.

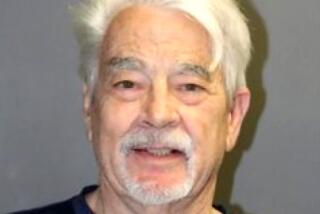

Nicole, who spoke on condition that her full name not be published to respect her privacy, was one of 21 women McGrew propositioned and harassed during VIN verification appointments, according to records from a 2016 internal investigation obtained by KQED and the California Reporting Project. Four women said McGrew offered to pass their vehicles if they would go on a date or to a nearby motel with him. Two said McGrew sent them text messages soliciting sex after he took down their phone numbers during a VIN appointment. Fifteen described McGrew making comments that ranged from proposing sex to asking intrusive personal questions.

McGrew resigned in 2017 when the California Highway Patrol notified him that it planned to fire him for a variety of misconduct, including improperly trying to foster relationships with members of the public, making inappropriate sexual comments and propositioning women for sex while on duty, the documents show.

The records provide details about the type of sexual misconduct by law enforcement that remained secret for decades in California until a landmark transparency law required agencies last year to publicly disclose a variety of documents, including investigations of officers found to have committed sexual assault while on duty. The Right to Know Act has exposed repeated instances of abuse, ranging from correctional officers in prison and jail who assaulted women under their guard to an officer fired for soliciting sex from an arrestee and one accused of beating and raping his girlfriend.

In McGrew’s case, the CHP did not refer him to the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office to decide if criminal charges were warranted. A CHP spokeswoman wrote in an email that “had there been sufficient evidence that a crime had occurred, it would have been investigated and potentially referred to the district attorney’s office.”

The district attorney’s office declined to comment on the case. The California Assn. of Highway Patrolmen, which represented McGrew, also did not respond to requests for comment.

Efforts to reach McGrew were unsuccessful. The CHP records show he admitted making the comments during VIN inspections but argued that termination was an excessive punishment after his 14 years of service.

“While I do not dispute that I made inexcusable comments to members of the public, the remarks were never mean-spirited,” he wrote in a letter to internal affairs.

Former U.S. Attorney for Northern California Joe Russoniello, who reviewed the internal affairs files, described McGrew’s conduct as “a wanton abuse of his badge” and said he was shocked the CHP did not refer McGrew to the DA.

“An agency needs to show that it’s serious about rejecting this kind of behavior,” Russoniello said. “And the serious way to do that is a criminal referral.”

South Pasadena Police Cpl. Ryan Bernal realized he was in trouble.

Phil Stinson, a criminal justice professor at Bowling Green State University in Ohio who has studied police crime, said officers like McGrew are often dismissed as “bad apples,” but that such behavior is normalized in many U.S. police departments.

Victims are often in a vulnerable position, and McGrew held particular sway as a result of his work. A registered vehicle is often key to a person’s mobility, employment and family life. Without proper registration people can face fines, or even lose their car.

“You’re dealing with a law enforcement officer who has a gun and a badge. They’re a person in a position of authority,” Stinson said. “And it’s very threatening for a woman to find themselves in that situation where the officer’s suggesting that they engage in a sex act. It’s absolutely terrifying.”

The number of times the CHP has disciplined an officer for sexual misconduct in the past five years is still unknown. A coalition of news organizations including KQED and The Los Angeles Times requested such records on Jan. 1, 2019, but the agency stalled for over a year before providing a single case file. In May, KQED filed a lawsuit against the CHP to force disclosure. The agency produced the internal investigation of former Officer McGrew shortly thereafter.

The agency has also released its investigation into former CHP Officer Timothy Larios, whose romantic relationship with a female confidential informant compromised an interagency narcotics operation and endangered the woman. Larios retired when the CHP notified him it was moving to fire him, the records show. A third file details the agency’s probe into former Officer John Frizzell, who was fired in 2014 for fondling a woman’s breasts during a traffic stop and asking another female motorist to lift her shirt.

In both cases, the documents give no indication that the CHP referred the officers for prosecution.

Records show the CHP began investigating McGrew after a woman made a complaint in 2016. Like Nicole, this woman made an appointment with McGrew to get her VIN verified so she could get her car registered with the DMV. She had her son with her.

McGrew gave the child a CHP sticker and looked at the vehicle.

McGrew then told the woman he would pass her car if she went to a nearby motel with him, according to the documents. The woman, who spoke Spanish, didn’t immediately understand what McGrew was asking. So McGrew repeated the proposition twice.

The woman went inside the office to complain about McGrew’s behavior. A sergeant asked her if she misunderstood McGrew due to the language barrier and if she’d been drinking or taking drugs. She said there was no misunderstanding and that she wasn’t under the influence.

“She could not explain the expression on Officer McGrew’s face, but she said he was smiling when he asked the question about getting a motel room,” the documents say.

As part of the internal investigation, the CHP sent three rounds of surveys to about 150 women ages 18-40 who’d made appointments with McGrew during his time as an inspection officer.

The CHP improperly redacted dates showing the length of the investigation and time span of McGrew’s abuse. But it is clear that the agency’s investigation did not include anything in the officer’s career before he was assigned to vehicle inspections.

By limiting the scope of the investigation to those over 18, investigators may well have missed more vulnerable victims.

“What about the 16- or 17-year-old driver that may own a car that he had come into contact with?” Stinson said.

One woman who said she felt violated after her experience at the CHP office told investigators that McGrew asked her what she would do for him if he passed her car.

“Officer McGrew asked her what she was going to do for him if he passed her car. She said she tried to laugh it off, but believed it was inappropriate,” according to the records. “She said he then made comments about ‘handcuffing’ her and getting her in the ‘back seat of her car.’”

The woman said McGrew “mentioned taking her to a motel at the end or up the street.”

McGrew admitted to investigators that he had made inappropriate comments to women while on duty, but said he never intended to act on them. When asked why he propositioned the women, McGrew replied; “Just to see if they’ll say yes,” according to interview transcripts in the investigation file.

McGrew, however, did date at least one woman he harassed on the job, he told investigators, and he repeatedly texted another for a few months. Both said they cut off contact with him after his explicit messages made them uncomfortable.

McGrew solicited two other women for sex via text message after their appointments. Documents show that McGrew got rid of that untraceable prepaid cell phone before investigators could look at it.

Many of the women told investigators they didn’t file complaints about McGrew because they were afraid of what he might do with the power of his office. One reported being scared to come back to the CHP for her follow-up appointment because she would have to see McGrew again.

Among the ranks of protesters who have filed complaints, joined lawsuits and pushed back against tactics used by area police agencies are women who say they were groped, sexually harassed or inappropriately searched.

Nicole recalled the moment when McGrew told her he would pass her car if she went out with him. She said she was suddenly hyper-aware of her surroundings — alone in a deserted parking lot with a man who was sitting in the front seat of her car.

At first, she said, she tried to laugh off his proposition. She needed him to sign off on her car’s VIN. But McGrew didn’t drop it; he kept asking. Twice more, she says, he offered to pass her car in exchange for a date.

“At that point I just shut down completely, and just kind of gave him this look like, ‘I’m so uncomfortable,’” she says. “And then he got more awkward and finally just kind of stepped out of my car, handed me paperwork and said I was good to go. And then I drove off.”

Nicole said she was contacted by CHP investigators months later and told them what had happened. She said the CHP never got back to her to let her know what happened with McGrew. She says she would also have expected the agency to make some changes as a result of the investigation. They have not.

“No changes to CHP policy were necessary because the behavior was against policy then and is today,” a CHP spokeswoman wrote via email. “The employee’s conduct was investigated and the employee was appropriately disciplined.”

In the three years since this happened, Nicole says she has thought about it a lot. Her father was a police officer and before this experience, Nicole says she felt really positively about police. She doesn’t anymore.

She says she would have liked the CHP to do more intensive screening of potential officers to weed out people like McGrew.

“How does someone like that even get that far?” she asked.

This article was reported by KQED and produced as part of the California Reporting Project, a collaboration of 40 newsrooms across the state, including The Times, to obtain and report on police misconduct and serious use-of-force records made public in 2019.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.