- Share via

Jennifer Trujillo made a 30-minute trip from her home in San Diego County to the country roads of Wildomar in Riverside County for the first time in weeks.

For the last year, the Pala resident had made the trek up every Sunday to attend the service at Bundy Canyon Christian Church, a complex of colorful old-timey buildings along a rural road.

The coronavirus outbreak had sidelined Trujillo, 37, from her trips to church, leaving her to reading the Bible and practicing her faith at home. She knew about the worries of church services leading to outbreaks of COVID-19. That health officials criticized such gatherings as posing a public health risk to parishioners and others they may come in contact with.

But Trujillo would not ignore the call of her pastor to return.

“I feel safe around this community,” Trujillo said. “The word that the pastor gives forth is amazing and its better in person. I just wanted to go back.”

And so she did on a mid-July Sunday to an all-too-familiar scene of parishioners packing the pews. She was instructed not to sit next to anyone outside of her immediate household members.

It was a vain attempt at social distancing.

After scouring for a seat, her 9-year-old daughter Morgan and Trujillo settled for a spot near the center of the pews. Like others, they were squeezed in closer than six feet from other people. A fan conjured up a light breeze. Three vocalists and a drummer performed on stage as dozens of people sang along.

Churches across the state have been whipsawed by state closure and reopening orders, as church events have been tied to coronavirus outbreaks. In May, infections tied to singing in a church service in Redwood Valley and two more outbreaks from Mother’s Day church services in Mendocino and Butte counties drew concern from public health officials. Cases linked to singing during church services have drawn the ire of scientists and even some church leaders.

Still, Bundy Canyon kept its usual choral arrangement as the congregation swayed their arms like concertgoers to the singing.

When the services in this church along Bundy Canyon Road began, congregants greeted one another with hugs. Few wore masks.

“I will give power to my two witnesses ... these men have power to shut off the sky so that it will not rain during the time that they are prophesying and they have the power to turn water to blood and to strike the earth with every type of plague,” Randy Eichert intoned from the pulpit as he read from Revelations.

But whatever final judgment the junior minister preached about — the pandemic seemed, at the moment, far from a growing concern.

The tension between safety and faith has coalesced in the suburbs of Southern California. In parts of California’s so-called Bible Belt, the controversy over rising cases of infection and deaths related to the coronavirus has not stopped residents from packing in-person services.

It’s what his flock wants, Bundy Canyon Christian Church Pastor Michael Khan said.

“They didn’t like being apart at all,” Khan said. “We have trust in God that nothing will happen. Since the start of the pandemic, not one of our members got sick or lost their job. The church will always be victorious.”

It is an altogether not surprising development in this part of Southern California. In May, Riverside County was quick to rescind stay-at-home orders and was among the largest proponents for reopening services.

In the county’s southwest corner, conservatism and a strong evangelical base distinguish this suburban region from the rest of the Golden State.

Church is a big part of the community stretching across the I-15 from Temecula to Wildomar. This nexus for megachurches and more than 10 Mormon congregations took the first chance to open up its houses of worship when the first lockdown orders eased. And when Gov. Gavin Newsom called for the suspension of indoor in-person services the second time around, some ignored it while others moved their worship outdoors, including in parking lots.

Despite the state orders, Bundy Canyon Christian Church hosted about 60 members without masks in their barnyard church — a larger crowd than they normally received at their 10 a.m. service. Congregants tried to space themselves out and were restricted to sitting next to only people who lived in the same household, per the church’s guidelines. But as the building got closer to reaching capacity, that task became harder.

“The church isn’t very big, we keep families close but others spaced out. We’re not breaking the law per se,” Khan said.

That is, not God’s law.

“This pandemic has instilled a level of fear in people, and some is unwarranted,” he said. “The church is trying to help people lose this fear through God.”

After weeks of online-only services, Khan reopened in June and invited only members of his worship team — the people that lead services, including members of the choir. But slowly, more people came back.

Khan said no one from his church has fallen ill due to COVID-19 or lost their job.

“I’m preaching and teaching something I live. We have faith in God that nothing will happen to us,” Khan said. “And being present is more powerful than it being taped. It’s like photography, every time you reprint it loses its color. We want to be in that presence.”

Menifee resident Cindy Meddinna wasn’t worried about catching any virus when she returned to Bundy Canyon Christian Church. The church was basically a second home to her. She couldn’t wait to get back.

“I don’t need the building to worship. The Lord is with me, but I gotta have my fellowship with all of my teachers, leaders and my church family,” Meddinna said.

To her, being able to return to church overrode any concerns about COVID-19. In fact, she had none of the latter.

“I am covered in the blood of Jesus Christ and I don’t believe in COVID, and God will never allow me to contract it,” she said. “I think it’s more of a political thing.”

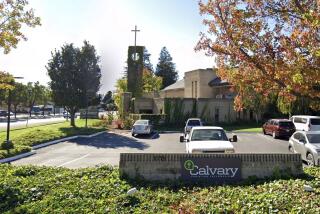

In Temecula, 61-year-old Lisa Correa, a parishioner who also works as Calvary Chapel Temecula Valley’s children’s ministry director, reclined back in her seat. She arrived 15 minutes early for a service, which normally would guarantee her a prime spot in the church.

But unlike at Bundy Canyon Christian Church, services had changed here. Instead of sitting in pews, parishioners would sit on lawn chairs arranged across the church’s parking lot. In addition, they would have to bring their own Bibles to minimize the spread of the virus.

Correa’s husband, Frank, 61, who is an assistant pastor, said the online services “didn’t have the same effect. ... I think we all missed church. You can hear the message online, but you lack the fellowship.”

“Even though it’s fellowship at a distance, it’s still fellowship,” his wife added. “And the singing going on doesn’t concern me since we’re far back.”

Pastor Chris McPike of Calvary Chapel said the pandemic had brought about a sense of isolation. The changing directives from the state were also disorienting, he said.

He had to quickly adapt to online services by posting live videos on Facebook for his congregation to view from the safety of their homes. The pain of preaching to a computer was short lived, though, as he was able to reopen his church doors to 25% capacity in June when case numbers slowed. But just as he was getting into the groove of his socially distanced indoor sermons, the rug was pulled from underneath him.

Two weeks ago, the same feeling of disappointment flooded in as cases across the state spiked and he was forced to cancel services that were just coming back to life.

McPike had no intention of breaking the law, so he went the route of businesses such as those of hairdressers, nail salon technicians and restaurant owners: He took the word of God outdoors.

“I’ve been through it all as a pastor,” McPike said. “Y2K, H1N1, and still nothing compares to how COVID has impacted our church. We want to provide that spiritual experience, but we also want to keep everyone safe.”

During a recent 8 a.m. service, families attempted to find refuge under the receding shade cast from the building; they squinted from the sun as they leafed through their personal copies of the Old Testament and awkwardly waved to their neighbors several feet away.

Most congregants wore masks. Temecula residents John Wellons, 39, and his wife, Kimberly, 40, felt secure not wearing masks because they were sitting near the back in the parking lot. The couple ached for the days of yore.

“I think we’re in a place where we’ve moved past the virus and we need to move back to some normalcy, so it doesn’t scare me,” Kimberly Wellons said. “We’re called as Christians to gather and worship the Lord, so that’s what I intend on doing. The safety aspect doesn’t scare me.”

As for the virus that has upended the world?

“My God is bigger than coronavirus,” she said. “I’m not concerned.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.