Some autopsies remain secret for years. Families of those killed by police want that changed

It is a roster of tragedy and violence, a list populated with those famous in life and those plucked from obscurity by the exceptional circumstances of their death.

Elizabeth Short, known as the Black Dahlia, is an enduring member of the list. Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman are still there, as is Susan Berman, the writer whom Robert Durst is charged with killing at her Benedict Canyon bungalow. The Notorious B.I.G. was on the list for about 15 years after being killed in a drive-by shooting.

The vast majority are more recent entries, including Andres Guardado, the 18-year-old fatally shot in June by a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy in Gardena.

These are people whose deaths have been under a so-called “security hold” by the Los Angeles County medical examiner-coroner’s office, a status that prevents public disclosure of their autopsies, often for months, years or, in some cases, indefinitely.

At any given time, more than 100 cases are under a security hold. This sealing was considered a routine procedural function, imposed almost always at the request of police or prosecutors, to provide a shroud of secrecy during the investigation of complex, high-profile, mysterious or unusual deaths. Usually, the hold is lifted only when the requesting police or prosecuting agency gives the green light.

But in recent years, the practice has been thrust into the spotlight when on-duty police officers have killed members of the public — cases in which anger and skepticism have fueled calls for accountability and transparency, and in which the security hold has only compounded flaring distrust.

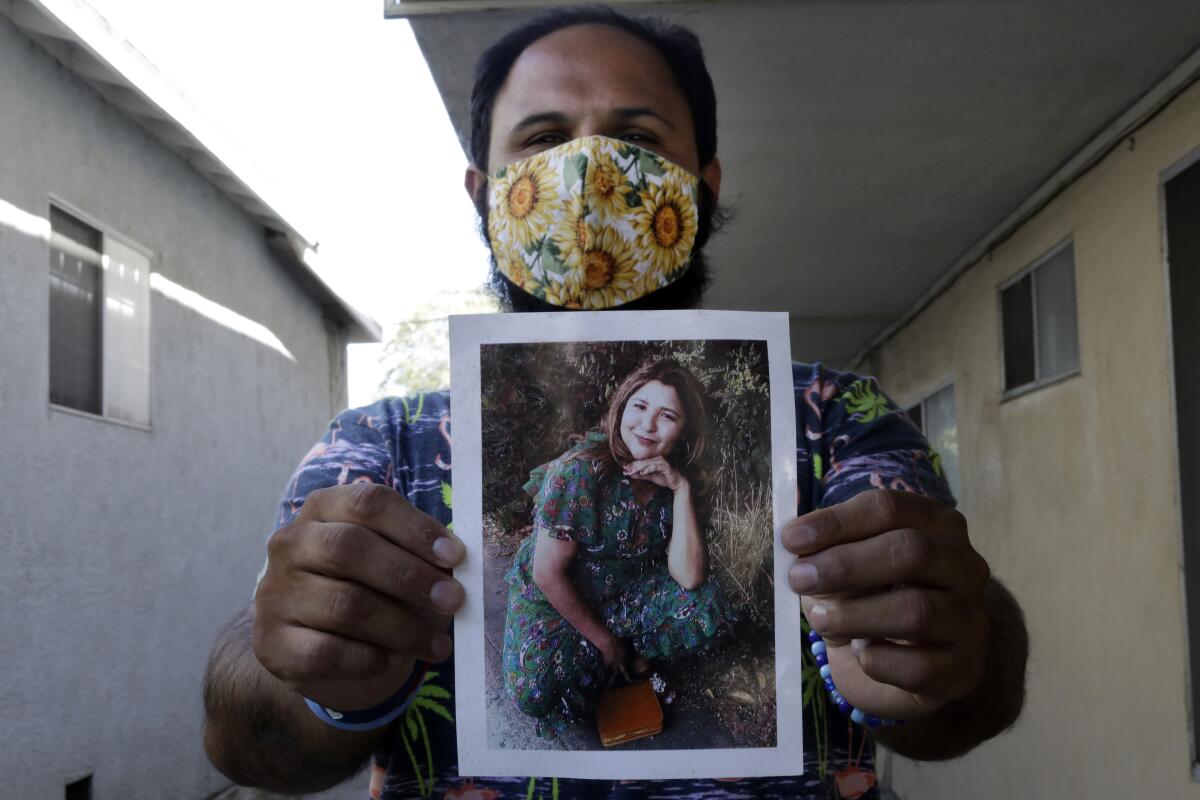

The hold has set the coroner’s office at the center of an impassioned debate that came to a head with the death of Guardado, who was working as a security guard at an auto body shop June 18, when he was approached by officers and ran, his family said. Deputies said Guardado produced a firearm during the chase. His killing spurred days of protests and demands for justice and answers.

After Guardado’s family publicly shared the results of an independent autopsy, L.A. County Chief Medical Examiner-Coroner Dr. Jonathan Lucas unilaterally bucked the hold installed by the Sheriff’s Department and released the full coroner’s report, confirming that the 18-year-old was shot five times in the back.

“I believe that government can do its part by being more timely and more transparent in sharing information that the public demands and has a right to see,” Lucas said in a statement.

Sheriff Alex Villanueva was furious and swiftly rebuked the disclosure, saying it jeopardized the ongoing investigation as well as any “future criminal or administrative proceedings,” even tainting potential witnesses.

Authorities maintain that security holds are essential for preserving the integrity of cases, and for the families of many homicide victims, the practice has been largely without controversy. The families often form close bonds with detectives or district attorneys and have a greater degree of trust as authorities try to prosecute a killing.

But for the relatives of those killed by police, the security hold is one in a series of ways in which they are treated differently, blocked from officially knowing the details of their loved one’s final moments.

“Family members speculated it was a way of harassing them, making their loss more difficult because they couldn’t have a determination into how their loved one was killed,” said Lael Rubin, a retired L.A. County prosecutor who serves on the civilian commission overseeing the Sheriff’s Department. She noted cases in which security holds have been in place for two years or longer.

“The official word was, ‘We request a security hold for further investigation,’ but it does seem suspicious,” Rubin said. “If you haven’t completed your investigation in two years, what are you doing?”

Under state law, coroner’s reports are public record. The packet is often three reports in one: toxicology tests, an autopsy and an investigative summary. The documents can be incredibly detailed, with a medical history, a listing of prescription drugs the person took and the doctors who issued the pharmaceuticals, descriptions of the person’s anatomy and the manner in which they perished.

Photos or videos from a death scene are not released, but a report can include a diagram of a body, along with descriptions of tattoos and piercings.

A hold means the death does not show up in the coroner’s online database, and staff at the office have “limited access to case information,” Sarah Ardalani, spokesperson for the Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner, said.

The security hold has become a standard feature in the aftermath of a celebrity’s death, including singer Whitney Houston, actress and writer Carrie Fisher, actor Paul Walker and the wife of actor Robert Blake. In these cases, the hold prevents salacious tidbits from reaching tabloids and is usually lifted in three to six months, when the full report is complete.

“Its main role is to ensure that the facts of the case are held until the investigation can be thoroughly vetted,” said Dr. Mark Fajardo, the chief forensic pathologist of Riverside County and former coroner of L.A. County.

Of the 8,000 or so deaths reviewed each year by the L.A. County coroner’s office, a small fraction are kept secret.

“It buys a little time,” said Craig Harvey, the longtime chief of investigations for the county coroner, who retired in 2015. Harvey said detectives and prosecutors may consider confidentiality as essential to identifying a suspect who had information that only the killer could know.

For example, LAPD Det. Meghan Aguilar said in a statement, the autopsy report may detail whether the victim was sexually assaulted and whether evidence of this was recovered — information that detectives and prosecutors would want to keep a lid on while pursuing a suspect. The autopsy may also reveal if there was a struggle before a person died and what type of injuries on the body would reflect this, Aguilar said.

Why the Simpson and Goldman autopsies remain under a hold is unclear. The LAPD said the 1994 killings are still considered unsolved, warranting the hold, but Judge Lance Ito, who presided over the criminal trial of O.J. Simpson, also appears to have effectively sealed the autopsies. The coroner’s office confirmed that the autopsies were put on a security hold via court order.

“It is my recollection this was agreed to by both the prosecution and defense,” Ito told The Times via email. Ito, who has retired, declined to explain why he sealed the autopsies, but he noted that photos of the autopsy were displayed and details of the victims’ cause of death were aired in open court by medical experts.

Security holds might also prevent “inflammatory” information from reaching the public without proper context; for example, a description of gunshot wounds in a person’s back, Harvey said.

“Because of the trauma that a bullet does to the body, it doesn’t necessarily mean the police shot someone in the back,” he said. “People may get worked up over something. But it may be explained, and it can make sense, and it can be presented to the grand jury or district attorney.”

For more than a year, the family of Paul Rea, 18, waited anxiously to learn more about how he was shot and killed by an L.A. County sheriff’s deputy during a routine traffic stop in East L.A.

Prosecutors concluded in May that the deputy acted lawfully, then closed their investigation. Rea’s family learned this from a Times journalist. Until late last month, the autopsy remained under a security hold.

Grainy security footage that captured part of the June 27, 2019, encounter appears to show Rea breaking from the deputy before he was shot four times. Deputy Hector Saavedra said he felt a gun in Rea’s waistband, but Rea never pulled it out, according to a report by the district attorney’s office.

“I want the whole thing. I want to read everything,” said Julie Diaz-Martinez, Rea’s grandmother. “As a family member, the autopsy is important, because you wonder, was he still breathing when they took him into the hospital? You wonder, how lethal was the first shot? How long did he suffer? Could it really have been prevented?”

A yearlong wait for a security hold to lift is common when people are killed by police, but the hold can stretch on for two years or longer.

“They’re looking for answers about how their loved ones died, and the coroner’s autopsy often is one of the few repositories of objective information about that, and it’s hidden from them,” said Sean Kennedy, a member of the Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission. He proposed that the coroner lift holds and make the documents public after a reasonable period of time, perhaps 60 days.

Walter Katz, a former public defender who served as the police watchdog for San Jose and deputy inspector general for the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department, said the delays go to the very heart of how those killed by law enforcement are viewed.

“They are not treated like victims of a crime. The whole mindset is: Whoever is shot by the police is the suspect, and the law enforcement officer who used force is the victim,” Katz said. “That’s how the homicide books created by agencies characterize it.”

Not every case in which an on-duty police officer fatally shoots a civilian receives a security hold, according to local law enforcement agencies.

LAPD Capt. Gisselle Espinoza said in a statement that security holds are “based upon the confidential, legal and the sensitive nature of a case.” She cited other factors, including protection of evidence and proper review by the district attorney’s office.

“If autopsy results are released during an active investigation, it can taint follow-up interviews from victims, witnesses or bystanders,” said Jennifer De Prez, a spokeswoman for Long Beach Police Department.

The LAPD has kept a security hold on the autopsy of Melyda Corado for more than two years. Corado was working on July 21, 2018, at the Trader Joe’s in Silver Lake when Gene Atkins rolled up, hostage in tow, after leading two officers on a lengthy car chase. Atkins stopped the car; ran toward the store, which was crowded with shoppers; and shot at officers. Police returned fire, and one of the bullets struck Corado, killing her.

“Mely Corado was not someone engaged with police. She was not a suspect in a crime,” said John Taylor, the attorney representing the Corado family in their wrongful-death lawsuit against the city and the LAPD. “So to have a security hold on her case has been baffling and confusing.”

“If there’s something that’s on the body as evidence that would be known only to the perpetrator of the crime, I can understand,” Taylor added.

The L.A. Police Commission has ruled that the officer who fired the shot that killed Corado acted in accordance with LAPD policy. Atkins has been charged under the “provocative act” murder doctrine for allegedly setting off the events that led to Corado’s death.

The security hold has remained. Albert Corado, a community organizer who now lives in his late sister’s apartment in Atwater Village, said he felt the secrecy was part of a campaign to block information.

Last year, the Corado family’s lawyers subpoenaed L.A. County for her autopsy; the coroner’s office denied their request and referred her family to an LAPD detective, according to court records. The family then successfully persuaded an L.A. County Superior Court judge to order the autopsy’s release. The city did not oppose the move in court but did not lift the security hold, either.

Albert Corado said he reviewed the report, and it confirmed what he already knew — his sister died from a gunshot wound — making its secrecy a source of anger and motivation.

“The harder they make it to give out information in the run-up to trial is to make you want to give up,” he said.

The LAPD told The Times last week that it had directed the investigating officer in the Corado case to remove the security hold. In a statement, the department said the report should be made available to the public this month.

Times staff writers Maloy Moore and Nicole Santa Cruz contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.