California is still thirsty after the recent series of winter storms, rainfall figures show

- Share via

California had a series of storms last week. Did that put an end to the state’s drought?

The short answer is no.

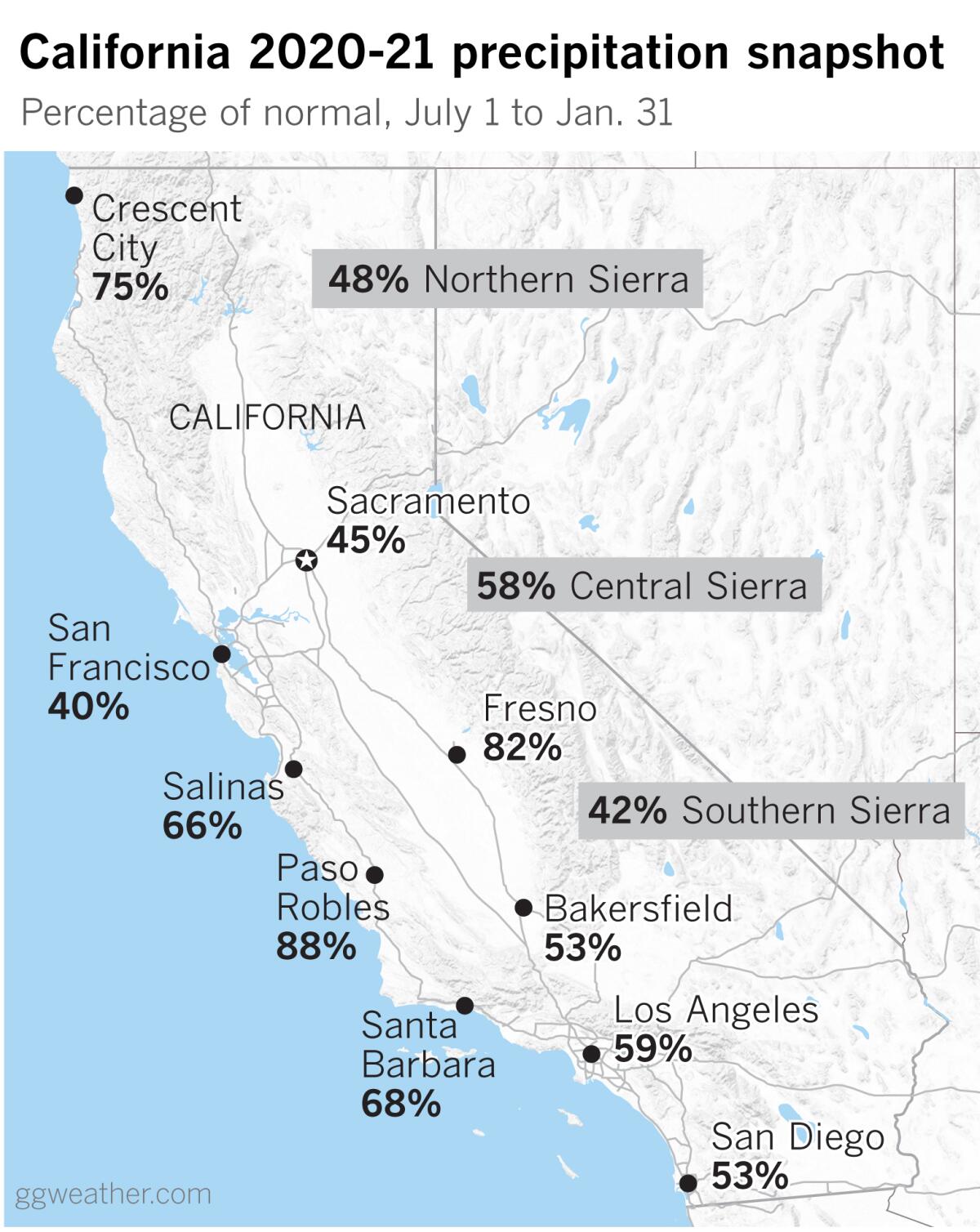

In spite of widespread precipitation from a recent series of winter storms, many places in California are near or below 50% of their normal season-to-date rainfall as of the end of January, according to meteorologist Jan Null of Golden Gate Weather Services.

Central California, the area most affected by last week’s atmospheric river, is an exception, according to Null, although those locations also hover below 100% of normal.

In Northern California, San Francisco is at 40% of normal, as is Santa Rosa. Sacramento and Redding are just a little better, with 45%. To the south, downtown Los Angeles is at 59% of normal; San Diego has received 53%; Riverside, 47%; and Irvine, 44% of normal so far. Palmdale stands at 37% and Lancaster at 29%. In the low desert, Palm Springs has gotten 21%. Needles has only received 3% of normal, and Imperial has gotten 0%.

Even though the week’s storms dumped large amounts of snow on the Sierra Nevada, precipitation indices show that the Northern Sierra is at 48% of normal; the Central Sierra, 58%; and the Southern Sierra, 42%. Snowpack in the Sierra is critical for California’s water supply because so many vital reservoirs are fed by snowmelt.

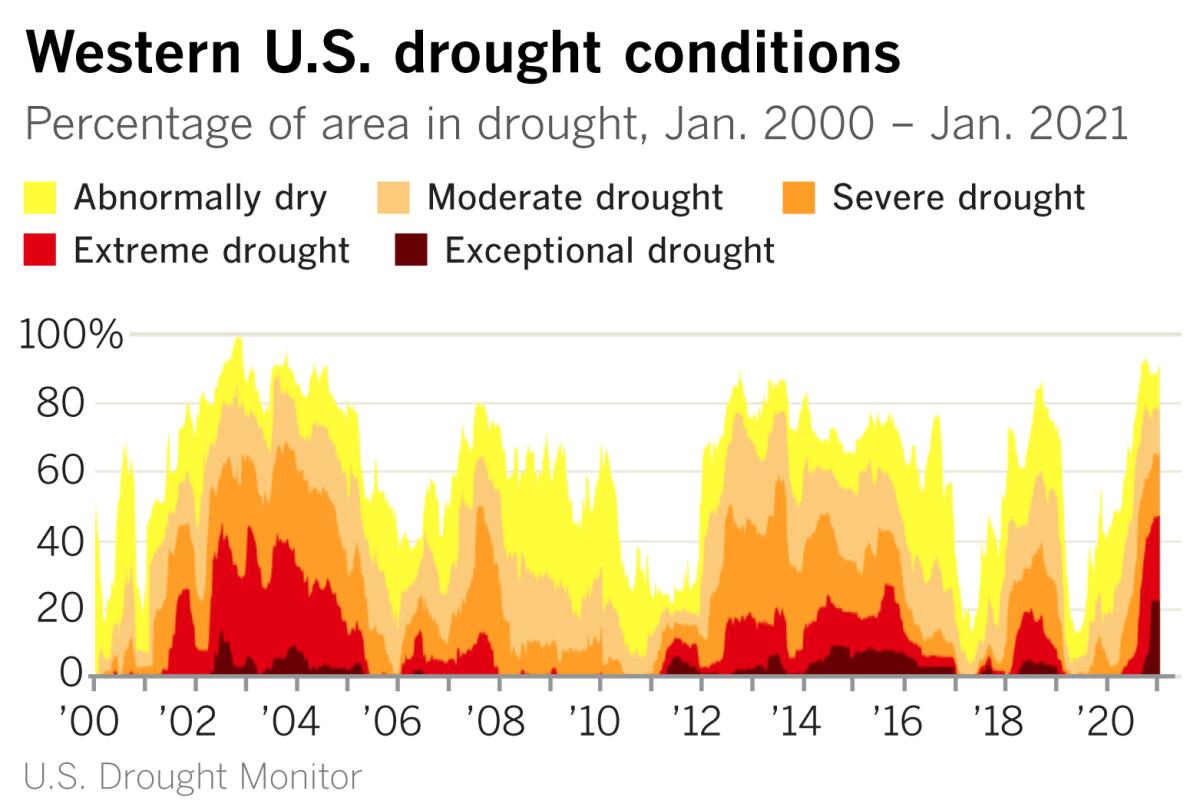

The U.S. Drought Monitor shows all of California in some level of drought, from areas classified as abnormally dry to exceptional drought. California’s drought is part of the broader drought afflicting the West. The Southwest, in particular, suffered a weak monsoon in 2019 followed by essentially a no-show monsoon in the summer of 2020. With a long summer of record heat, Utah and Nevada had their driest years on record in 2020, while other states in the Southwest endured a year that was among the driest in their histories.

This has been part of a drought pattern that has prevailed almost continuously for the last 22 years. The result has been that reservoirs on the Colorado River are less than half full. Millions of people in the Southwest depend on water from the Colorado, including the Los Angeles region.

Lake Mead, for example, behind Hoover Dam, is 143 feet below its full level. An unsightly bathtub ring as high as a 14-story building surrounds the lake, indicating where the water level used to be. The reservoir is as empty now as it was in the 1960s when Lake Powell behind the Glen Canyon Dam, farther up the Colorado, was being filled. And Lake Mead, which was at 1,086 feet on Wednesday, was projected to drop to 1,075 feet by the end of this year. The lake is considered full at 1,229 feet, and is currently at about 40% of its capacity.

As climatologist Bill Patzert points out, droughts are large, affecting not just a local area, but the entire Western U.S., for example. Droughts are long — not just year to year — sometimes spanning decades. And they’re intermittent. That is, the trend may be interrupted by a wet year or two, but the overall arc of the drought continues.

The colossal scale of the Hoover Dam-Lake Mead project makes it a large-scale monitor of the size and duration of the drought in the U.S. Southwest. “It’s like a giant snow and rain gauge,” said Patzert.

“Droughts can trick you. Don’t hyperventilate about being out of the drought from storm to storm,” said Patzert. “You have to understand the big picture.”

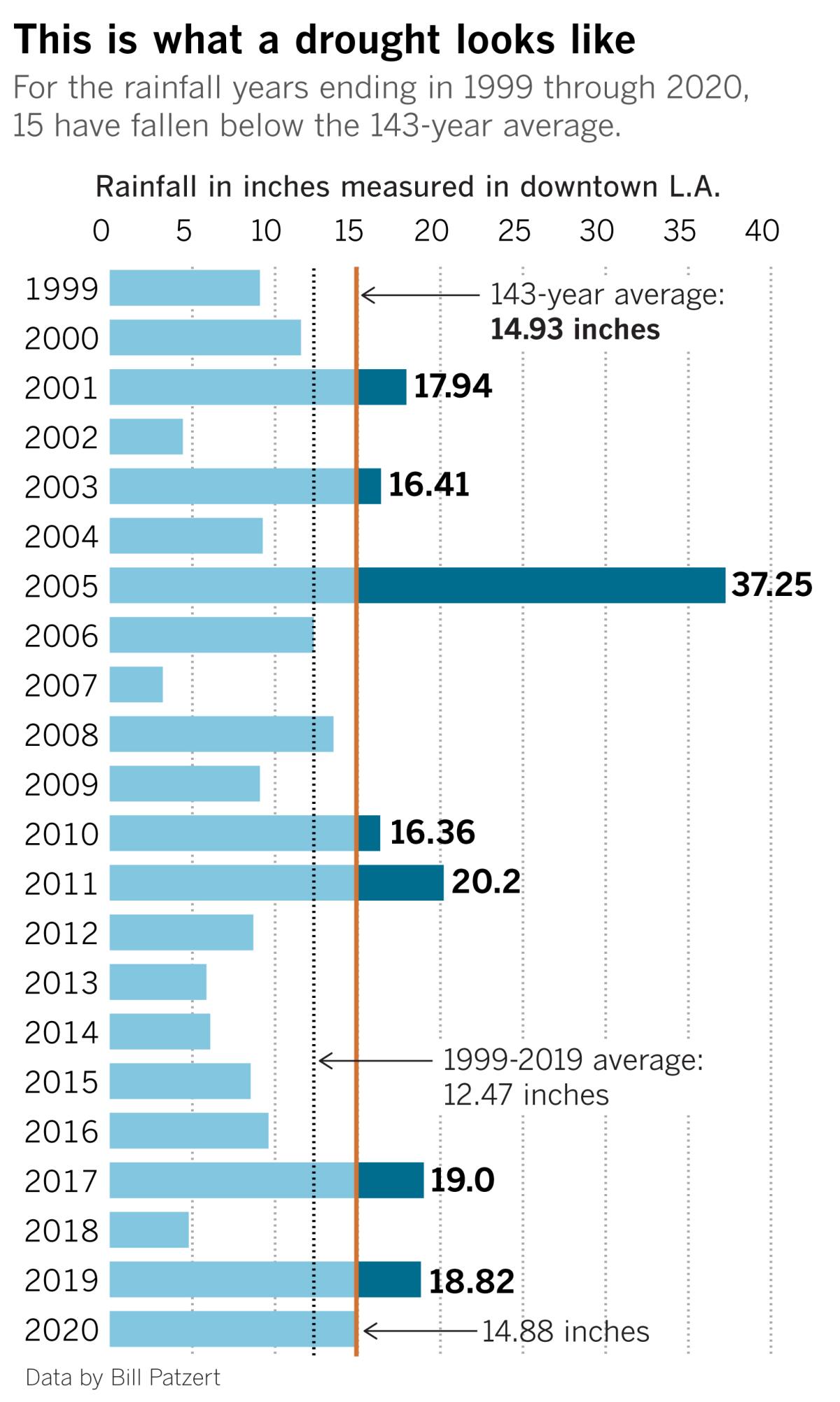

Patzert points to downtown Los Angeles as an example. For the last two decades, rainfall figures show that it has been more dry than wet. Years such as 2009-10 and 2010-11, or 2016-17 were wet — enough so that you might think the drought was over. But those seasons bracket the years 2011-12 through 2015-16, which were the driest five years in L.A. history.

And the dry years that dip below the 143-year average of 14.93 inches were much more numerous during the last two decades than the intermittent wet years. The result is a big picture of about 15% less water over the course of 22 years. If L.A. averaged 2.5 inches less rain for each of 22 years, that would total 55 inches, Patzert points out. That’s the equivalent of deducting almost four full average rain years over those two decades.

Patzert acknowledges that there are numerous definitions of drought, including ones that are man-made, but subtracting the equivalent of entire rainfall seasons a little at a time over decades certainly qualifies as one of them. That’s what Patzert means by the big picture.

Receiving average rainfall isn’t the solution. “If we had average rainfall, would we be out of the drought? No, we’re in catch-up mode,” he says.

Unfortunately, much of California and the West are below average and the immediate outlook doesn’t look promising. As climate scientist Daniel Swain writes, “There isn’t a great deal of additional precipitation on the horizon at the moment.”

That’s because a La Niña in the equatorial Pacific, following its typical, predictable pattern, continues to steer storms away from Southern and Central California.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.