- Share via

Dr. Christine Choi balances the iPad in her hands and scans the callers on the screen. It is a family gathering, pandemic-style: People in the foreground have video-called others, who have video-called a few more. A collage of faces peer back at her.

She asks them if they are ready. Yes, they say. Stoic.

Choi taps the corner of the tablet. The camera switches from her face to that of a lifeless man in a hospital bed. Their loved one, killed by COVID-19.

The quiet in the hospital room is pierced by wailing.

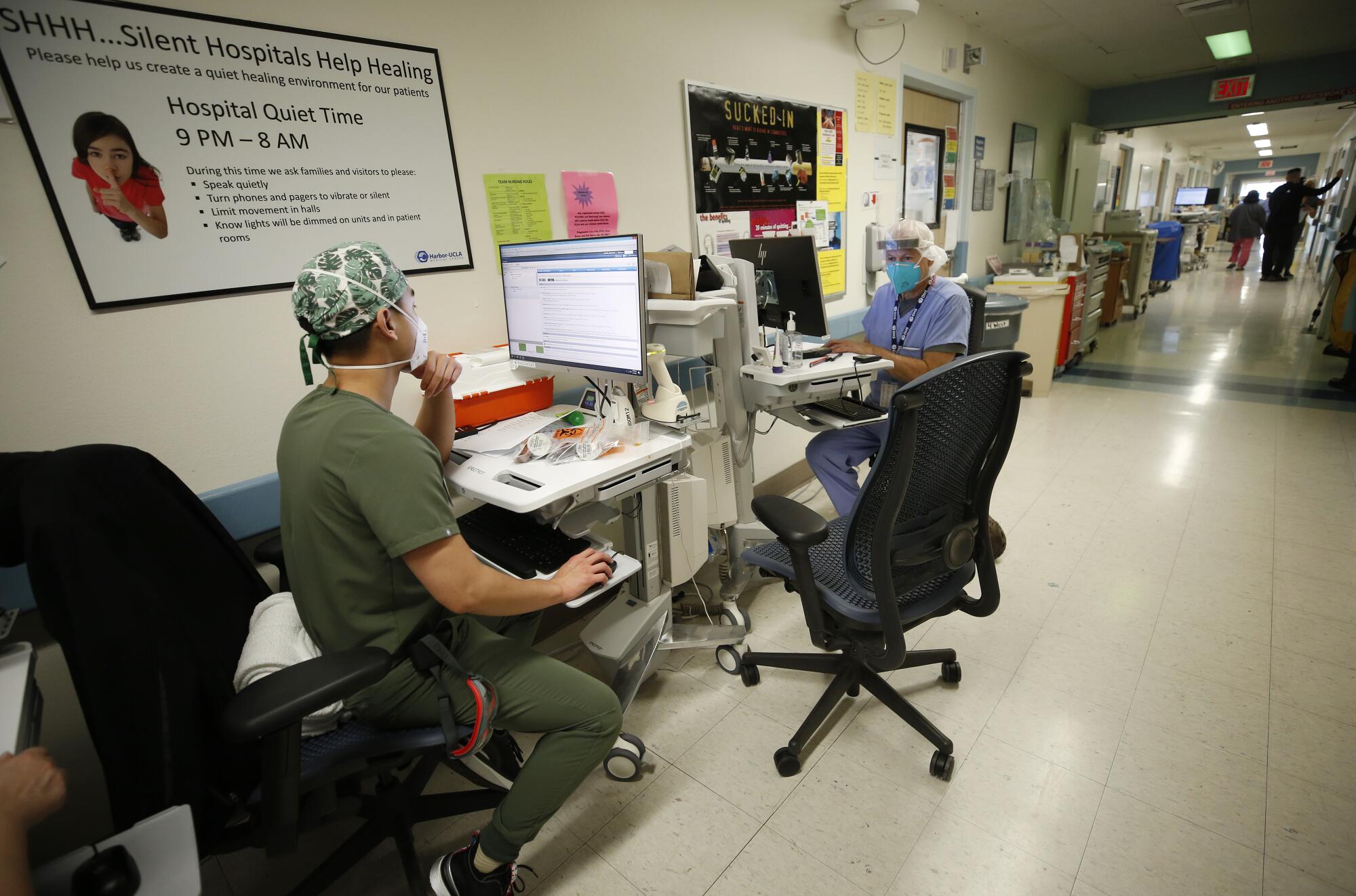

Choi is a tough, upbeat second-year medical resident at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, one of four public hospitals in Los Angeles County. But even for her, the pain of what she witnesses each day — what healthcare workers across the country have witnessed over the last year — can become too much.

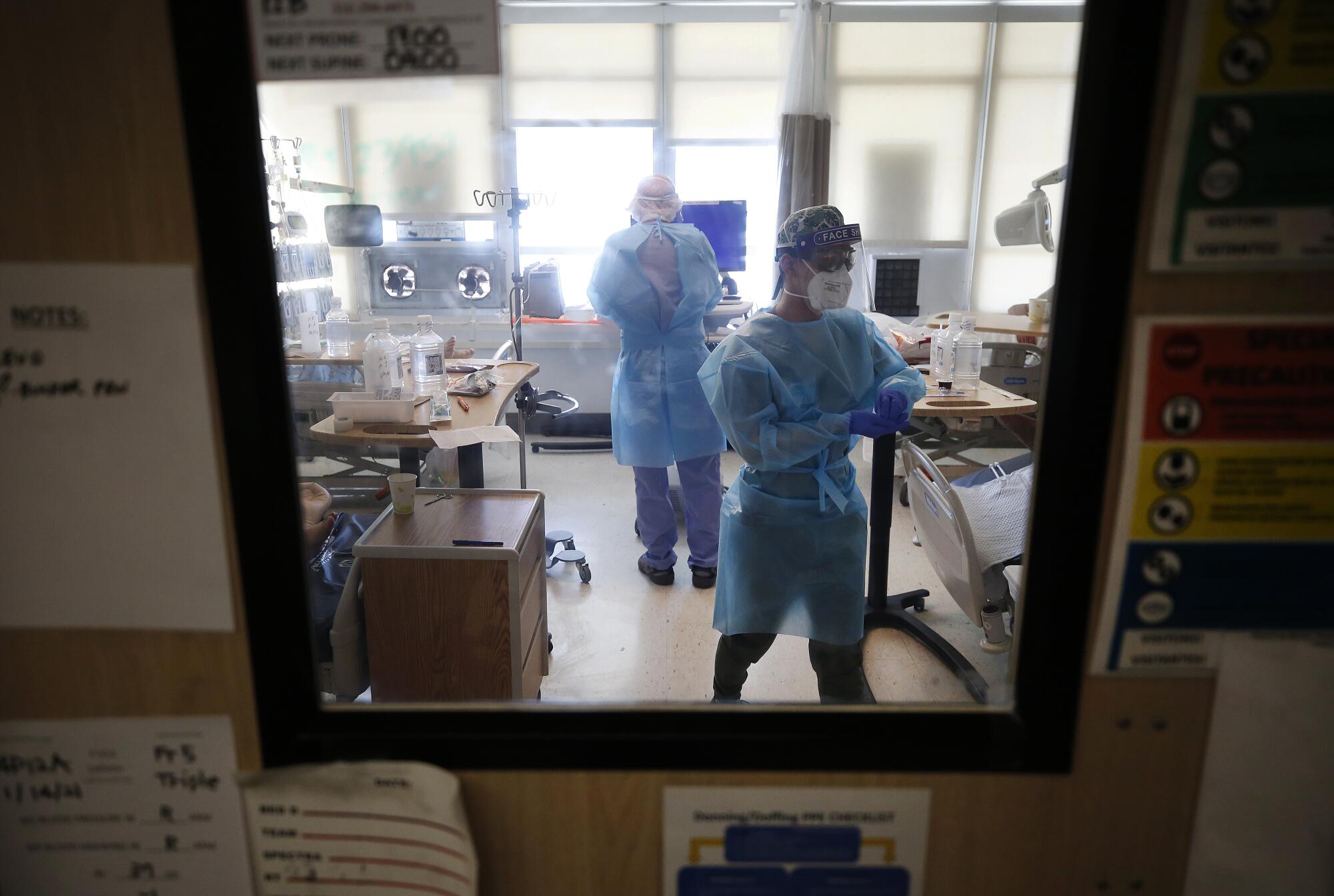

In the spring, when little was known about how the coronavirus spread and healthcare workers feared falling ill, Choi volunteered to enter COVID-19 patient rooms. She enjoys working in the intensive care unit, where the sickest patients are kept. She sustains an almost startlingly positive attitude despite frequent overhead pages alerting her to patients crashing and the constant beeping of the machines barely keeping them alive.

But this is the first time she has overseen this strange ritual born of the pandemic: death by FaceTime.

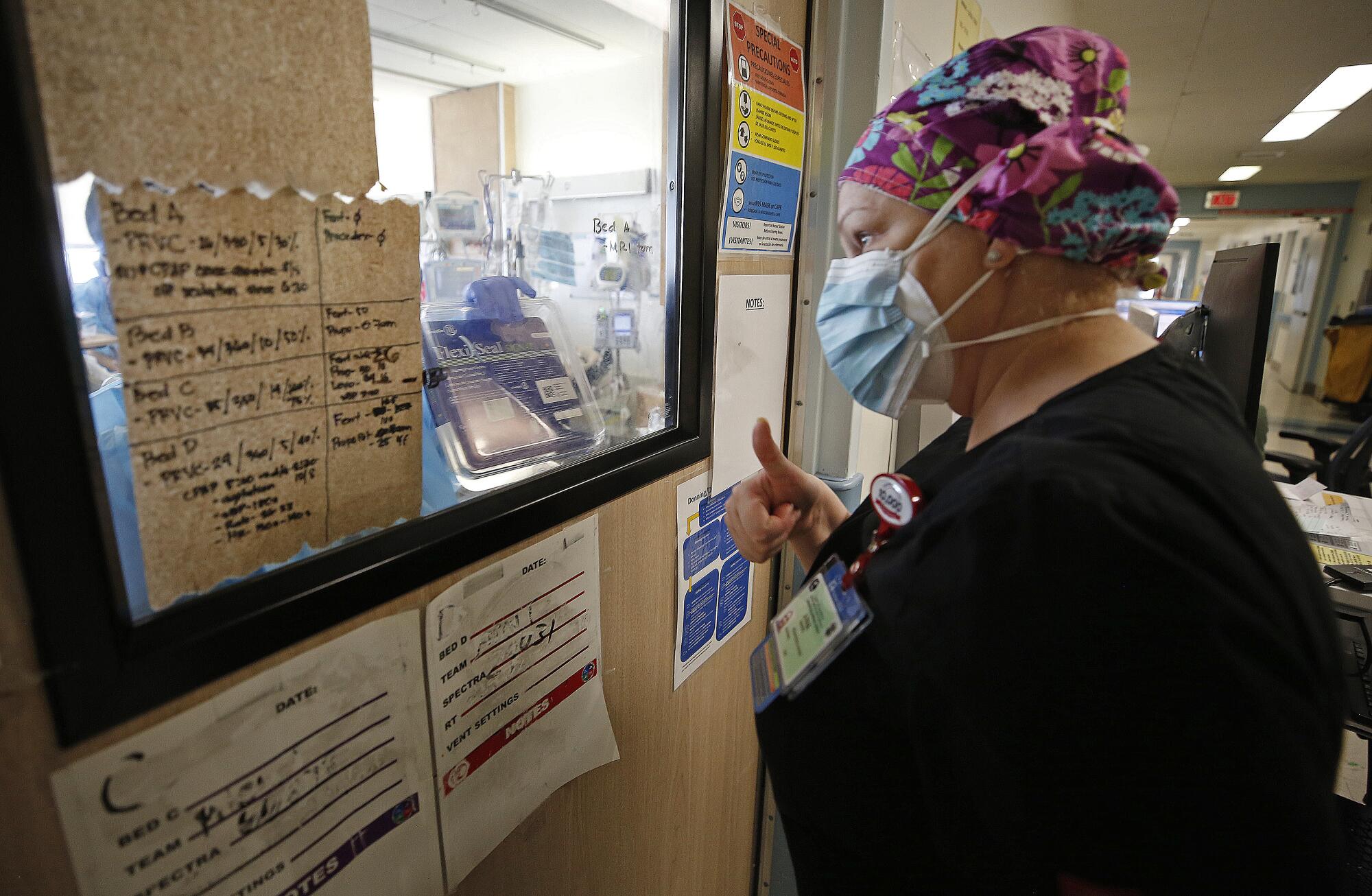

With families mostly unable to visit the hospital, doctors provide a final glimpse via video call of the person they had wished would be lucky enough to survive COVID-19. They angle the tablet or phone as families say goodbye to their uncle, sister, father or wife. Sometimes they hold the device for so long their arms begin to ache.

While Choi points the iPad at her patient, her own face is hidden behind the camera. She is silent, rendered nearly anonymous by her mask, gown and face shield. She is an extra in this scene, yet her eyes, too, are wet with tears.

The horror of the pandemic has unfolded largely outside public view and inside hospitals, piling a disproportionate share of the trauma on the people whose work takes them inside their walls. In California, where a massive COVID-19 surge has begun to plateau, more than 24,000 people have died since Nov. 1, most of whom succumbed in the hospital, with only doctors and nurses by their bedsides.

‘One can only be a hero for so long’

Being near so much pain will likely take a grave toll on medical workers’ mental health, experts say. Many worry that doctors and nurses will burn out or retire early and that the experience, unprecedented in length and scope, will trigger high rates of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder that will outlast the pandemic.

“At least with a natural disaster, it happens, people get scattered all over the place, property gets damaged or flooded, but then we begin to rebuild. We’re not there yet, and we don’t know when that will actually occur,” said USC social policy professor Lawrence Palinkas, who studies the psychological effects of disasters. “This event is almost a year in duration with no end in sight.

“One can only be a hero for so long.”

In Los Angeles County, there is little mystery to the heaviest spread of the coronavirus. Where crowded housing is worst, the COVID-19 pandemic hits hardest.

Healthcare workers have become conduits for the anguish of families and patients. They field hundreds of phone calls a day from anxious relatives. Nurses hold patients’ hands when they are intubated. Staff monitor their cellphones and reply to text messages. They pray for their recovery.

Fred Rogers famously advised to “look for the helpers” as a source of comfort during scary times. But the helpers need help too.

“The sound of the family members crying,” Choi said, “I probably will never forget that.”

Over the last year, the 32-year-old has worked many evenings in the ICU. Due to limited staffing overnight, the trainee doctor is frequently responsible for determining the care a patient should receive.

The options are grim. Many COVID-19 patients who are struggling to breathe need to be placed on a ventilator or they will die. But a ventilator doesn’t guarantee survival, and, even if they are removed from the machine, they may suffer memory problems, a loss of brain function or have a stroke and be unable to move their arms or legs, Choi said.

“I’m offering this guy two terrible options, and that’s how I feel about work: I can’t fix this for you and it sucks, and I’m sorry that the choices I’m giving you are both terrible,” she said. “The patient will say, ‘Help me. Tell me what do you think I should do?’ And I don’t have an answer.”

Since Nov. 3, approximately 23% of people with COVID-19 admitted to hospitals in L.A. County did not survive. The death rate has been unusually high since the winter surge began because hospitals could accommodate only the sickest patients as they ran out of space and staffing.

Therapy sessions

Hoda Abou-Ziab, the hospital’s lead clinical psychologist, said she worries that the flood of patients has stripped healthcare workers of the time necessary to process their grief. Abou-Ziab offers therapy sessions to medical providers at the hospital.

Nurses and doctors are already prone to high rates of depression and suicide, she said. The pandemic has introduced new fears of contracting the virus and bringing it home to their families, repeated exposure to death as well as an unprecedented number of very ill patients that can make healthcare workers feel helpless.

“To be able to sit with that discomfort, knowing you can’t fix it, or you can’t change it, it’s really hard, because healthcare workers are fixers,” Abou-Ziab said.

Choi recently treated a father and son both admitted to the hospital with COVID-19. Placed in the same room, they asked to keep privacy curtains open so they could see each other’s oxygen monitor.

The father died in the hospital. Choi spoke to his wife. A few days later, their son was placed on a ventilator. Though he is still alive, doctors have not been able to take him off the machine.

“They were a family, and they were together,” Choi said. “I can only imagine what it would be like to be that mom.”

Though the COVID-19 surge in L.A. County is slowing, there are still approximately 500 patients with the disease newly admitted to hospitals each day.

Harbor-UCLA has called in extra support from the Department of Defense to help triage the huge numbers of patients and has parked two refrigerated trucks behind the hospital to store dead bodies when the morgue becomes too full, as is common.

Healthcare workers typically turn to one another for emotional support, finding solace in their shared experiences, yet many no longer have the emotional bandwidth to take care of friends and colleagues amid such a prolonged crisis. Choi said she relaxes at home by watching comedies — “Schitt’s Creek” is a favorite — and talks to her partner, who also works in medicine. But the grief can overwhelm her too.

Just last week, an older woman with COVID-19 died in the hospital. Then, her husband, also admitted with the virus, began to struggle to breathe. Choi and her colleagues suspect he is approaching the end of his life.

The young doctor held a cellphone as each of the man’s children came on the screen to tell him that they loved him, Choi recalled. “And I was just bawling in my PPE.”

For some healthcare workers, the pain of the last year has morphed into exhaustion and anger. One ICU nurse described the blank look in her co-workers’ eyes and hugging them through personal protective equipment. One of her friends at work died of the virus in the spring, a loss that still aches.

The nurse, who works at an L.A. County public hospital but did not have permission from her employer to speak, said she, like many healthcare workers, is not accustomed to asking for help. But the pandemic has forced her to acknowledge that she too needs support.

“There are moments when I have wished I was dead so I don’t have to take care of people. I know that sounds really bad,” the nurse said. “A lot of my co-workers are depressed too.”

She feels disheartened by what she sees as a chasm between the devastation inside the hospital and the indifference with which the public treats the virus.

Over the summer, a middle-aged man was admitted to her hospital unable to breathe due to COVID-19, but insisted on leaving and said he was not sick, she said. The nurses inquired with the local health department about forcing him to stay, but learned they could not.

The nurse had to wheel him outside the hospital and return him to his family. Months later, her voice rises with fury as she remembers that she had given him doses of remdesevir, a medicine to treat COVID-19 of which there was a limited supply.

“After that I broke down and cried, because I couldn’t believe I’m helping someone and he truly believed he did not have COVID when his test results showed he did,” she said. “I realized we’re never getting out of this because there are so many disbelievers.”

Scott Byington, a critical care nurse at St. Francis Medical Center in Lynwood, said his hospital has also had patients whose family members wanted them discharged because they did not think having COVID-19 was serious. At least one of those patients died of the disease before the relative could take her home.

‘Their last piece of sanity’

“A lot of healthcare professionals are getting very edgy, and they’re losing their sympathy and empathy for people who don’t believe in this,” he said. “We’re in a place where everybody is holding onto their last piece of sanity.”

California’s unemployment agency was not prepared for the COVID-19 pandemic, an emergency state audit confirmed this week. Many of its issues with processing claims have been ignored for more than a decade.

Experts say that the long-term mental health effects of the pandemic won’t be understood for years, as most existing research focuses on disasters within a much shorter time frame. But there is a surprising finding from disaster research that will likely apply to COVID-19 too, said USC’s Palinkas.

When Palinkas studied people who survived difficult experiences, he found that some people thrived and the experience improved their self-worth. “It reminded me of that old saying: That which does not kill only makes us stronger,” he said.

Before the pandemic, Choi had wanted to be an internal medicine doctor who would work in an office. But treating COVID-19 patients has made her want to switch to a more hospital-based specialty and is considering additional training to become an ICU physician.

“It’s really, really emotionally difficult and stressful. ... The fact that I am quite possibly the last person this person speaks to before they are put under — and who knows if they’re going to wake up — I think that’s a great, great privilege,” she said. “It’s sad, but I’m very grateful I get to do this.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.