- Share via

FRESNO — In the Before (as their children call pre-coronavirus), Rene and Veronica Ramirez sometimes joked after a hectic day that they were “livin’ the dream.”

It was a dream hard-won.

For the record:

8:53 a.m. Feb. 11, 2021An earlier version of this post stated that pediatrician Veronica Ramirez was from Orosi. She is from Dinuba in Tulare County.

Veronica, a pediatrician, was the daughter of a single mother from Dinuba, a rural Tulare County community. Rene, an emergency room physician, was from the other end of the agricultural valley and had driven long, fog-shrouded roads to classes at Fresno State, becoming the first in his family of farm and factory workers to graduate from college.

When the pandemic hit, their dream put them at the center of a global catastrophe. They lived in a large, multigenerational household, where the risk of COVID-19 transmission would be magnified. Veronica was pregnant with their fourth child, and Rene worked on the front lines in a hospital, where treating the sickest patients carried the risk of bringing the virus home.

Then in January, Rene and Veronica each received their second dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, becoming part of what could finally be a turning point in the pandemic. Rene joked that he felt as if he had a new superpower, like out of one of his son’s cartoons.

Then to his shock, he began to cry. “I’m sorry — I don’t cry,” he said, and wept more as Veronica laid her head on his chest and rubbed his arm.

As the vaccine brought a glimmer of hope, the yawning darkness of the past year cracked open. The Ramirezes, like many, are facing what they have lost and what mercies they were granted.

A year ago, Rene and his colleagues with the Fresno campus of UC San Francisco, saw hospitals in Italy overrun with COVID-19 patients. They knew it was only a matter of time until it reached California’s fifth-largest city, which has some of the nation’s most concentrated poverty and is surrounded by farm towns where people work closely in the fields, packing houses and processing plants.

Some of the doctors bought RVs or built guest houses to keep themselves separate from their families. Recently, a senior doctor in the department said he would get the vaccine because he loved his wife and had not kissed her in eight months to protect her.

The Ramirezes decided they would trust Rene’s diligence to safeguard their household, which includes Veronica’s mother, Olga, 64, the family storyteller who makes homemade tortillas and chicken soup, and Veronica’s aunt, Lupe, 55, who paints scenes of her hometown of Pátzcuaro, Michoacán. Both help care for the children.

Their house has a bathroom near the garage. For a year, both doctors have stripped in the garage and went straight into a shower before they touched any of the family, including dogs Mickey, a Chihuahua mix, and Molly, a labradoodle.

Rene treated his first case of COVID-19 in February 2020. He called the CDC for a test for the patient and despite staying on the phone and insisting, was denied. The government would only test patients who had recently traveled to China. A Solano woman with no history of travel or contact with an infected person died of the virus on Feb. 6 and had been ill since January.

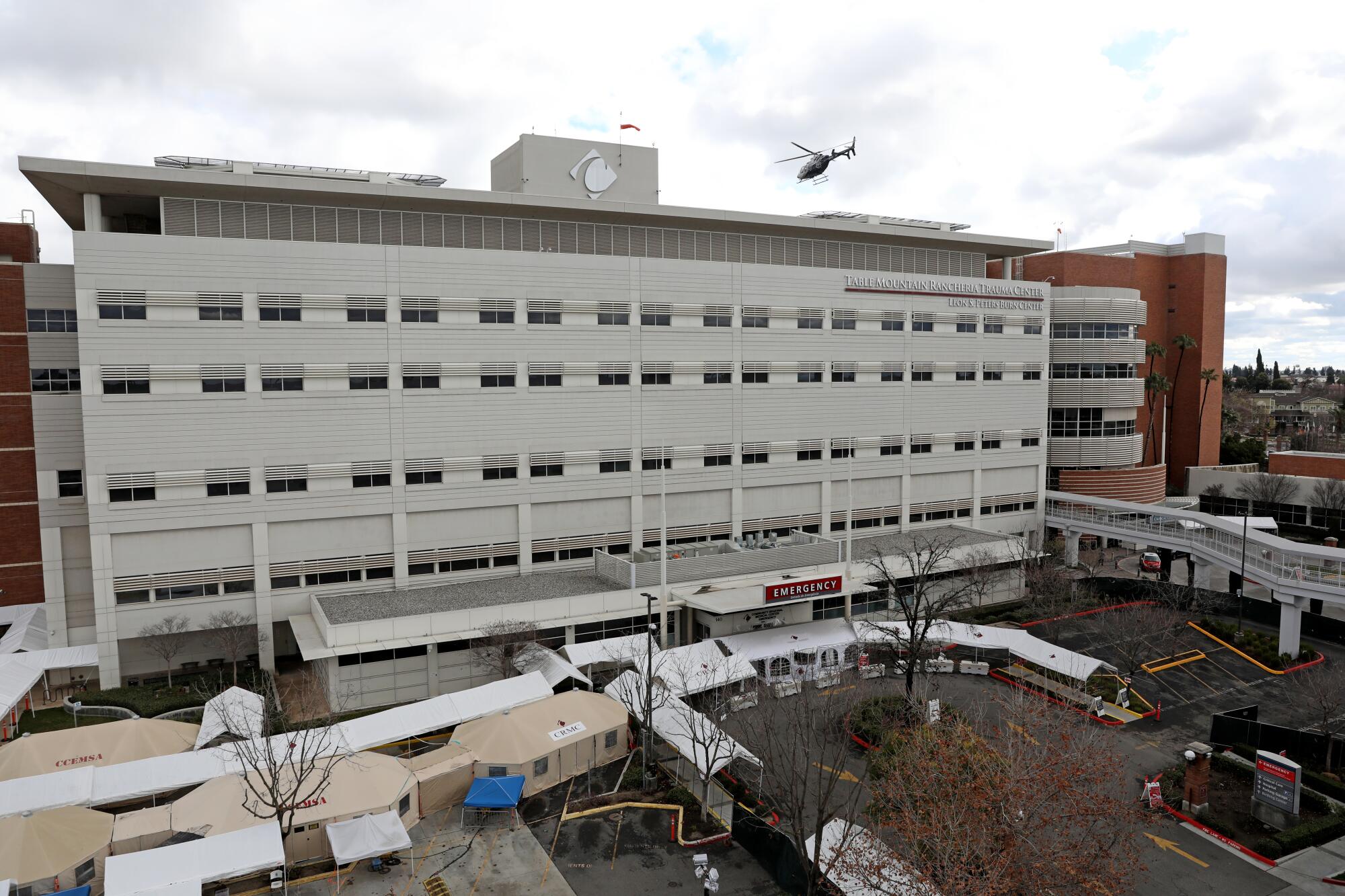

Rene isolated the patient and alerted everyone on that day’s shift. Soon the hospital was building tents in the parking lot for isolation and overflow patients.

On March 19, California went into lockdown. A week later, the Ramirezes’ obstetrician called Veronica to tell her she’d delivered the baby of a mother who tested positive for COVID-19. Veronica decided she still felt safer with her doctor than with one who may have been unknowingly exposed.

When they arrived at the hospital to have their baby, the parking lot was empty. As they walked up to the doors of Clovis Community Hospital, Veronica suddenly worried her husband wouldn’t be allowed in. Until then she had only been concerned about having a safe delivery, because, at age 40, she was considered high risk.

To her relief, he was allowed in the delivery room.

Baby Ryan Joseph proved a welcome pandemic relief to the family. On Easter morning, Rene rose before dawn to season and cook a large brisket over charcoal like he does each year. But sitting alone in his large backyard, he was overtaken with a dark, bitter feeling.

Even on a regular weekend, their family get-togethers numbered more than 40 people. “This is wrong,” he thought. “There should be cousins running around. Relatives should be jostling to get Uncle Xavier’s salsa. His grandparents should be holding my son.”

When Veronica returned to work, she found herself at risk because people would lie about their children’s symptoms on screening forms. They didn’t want anyone to think they had COVID-19. Some of them did. At first, scientists had thought children were protected, but she was soon caring for children with the virus.

In the summer, there was an uptick of cases at the hospital. The Ramirezes pleaded with their extended family to double down on protection and isolation.

By the fall, shifts in the emergency department were a nightmarish blur. One afternoon, Rene held an iPad for a dying patient saying goodbye to family — something the staff did many times a day — then was cheerful and upbeat while treating a sick child, then on to another wrenching goodbye. It was only the beginning of the shift.

By December, the virus overran hospitals in the San Joaquin Valley. At Community Regional Medical Center in Fresno there were zero beds available in the ICU. The COVID-19 ward had expanded to cover hallways and meeting rooms and the patients kept coming. Rene had dark bruises around his eyes and painful red bumps from wearing a medical-grade face mask so many hours at a time.

One evening, after another brutal shift, he joined his wife to pick up food at a taco truck. Many people in line weren’t wearing the cloth face masks that could help slow the spread of the virus. One unmasked man made eye contact with Rene and commented to his companions about some people being sheep.

“You want me to take my mask off? I’ll be happy to,” he told the man. “But you should know that I’m an ER doctor and I just did CPR and intubated a COVID patient.”

The man stepped back.

At home, Andrew, 11, their oldest son, worried about his 5-year old sister, Danielle.

“Because she is at that age where you would usually have your first play dates and she is missing that,” he said.

He felt sorry that his 8-year old sister Samantha missed having a First Communion with lots of family.

When Andrew was 8, a classmate was choking on a gummy bear and began turning purple. He successfully performed the Heimlich maneuver and it made national news.

The family joke is that it was because he’d been to medical school since his mother was pregnant with him during her studies.

This was family lore, part of the story about how Rene and Veronica met at band camp the summer before college and did everything together after that.

They both got jobs at Target to help pay for school and studied together. Rene proposed at their graduation, right after Veronica had her diploma in hand. Together they went to Drexel Medical School in Philadelphia where they learned medicine and how to navigate elegant dinner parties with a plethora of forks. Andrew was born at the end of their senior year.

They came home to be near their families and to be mentors to kids who could see that they looked like them and came from where they came from.

They bought the house with the big yard and the swimming pool. Rene and Veronica delighted in introducing their children to dance, karate and scouts and all the opportunities their parents couldn’t afford to give them. The children can turn down whatever lessons they want, other than piano. Piano is required — because their parents met at band camp.

As an ER doctor, Rene said he has long witnessed that life is fragile, that anything can happen to anyone at any time. He had seen death before COVID-19.

But in the Before, when he got home from the hospital, there was an immediate rush of kids and dogs and hugs. This is what he misses most.

That scene has not returned. Immunity may not mean that they can’t pass on the virus. Both doctors still decontaminate before entering their home. The entire family wears masks when they go out and practices social distancing. From the outside, little has changed.

But Veronica said that everything feels different, because she no longer worries that Rene will be one of the young doctors who gets the virus and doesn’t recover.

“Every day I notice — almost every minute — how much happier I am. Now I’m not worried that my husband won’t make it home.”

Rene said that when he broke down after getting vaccinated, it wasn’t mere relief at being able to care for patients without falling ill. He said that everything that he had pushed down, welled up: the frustration, anger, gratitude and grief. The exhaustion. The fear that people will refuse the vaccine or that the delivery of the shots will falter.

“I want my kids to be able to do the things they want to do. I want us as a couple to do the things we want to do. I want our son to know his grandparents,” he said.

“I want to go places. I want to hold my family the second I walk in the door. I want our life back.

“And we have this one shot.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.