Black people still aren’t getting COVID vaccines. This pastor isn’t having it

- Share via

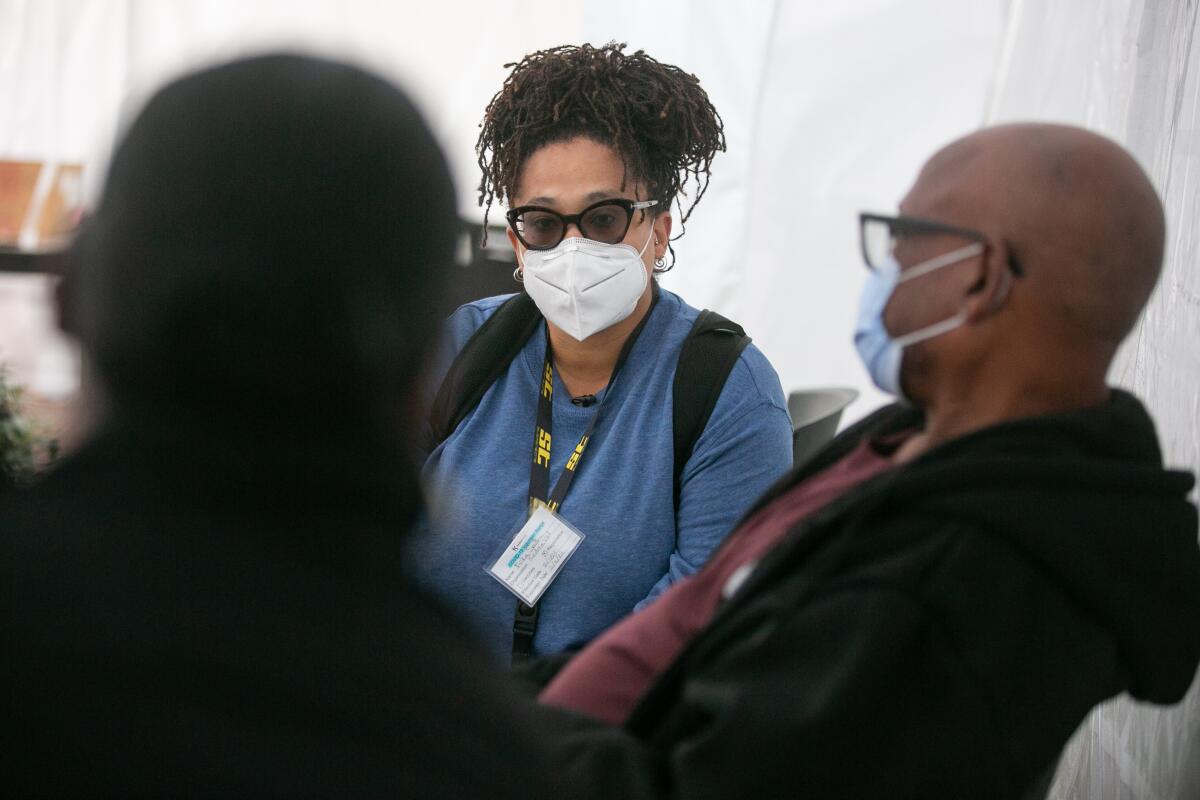

In his dark sunglasses and face mask, with a yellow beanie perched atop his head, Noel Jones tried to blend in with the crowd as he shrugged off his jacket and got his shoulder ready for the needle.

But he was recognized almost immediately.

“I’ve been watching you since forever,” a woman gushed as Jones fumbled with the paperwork for his COVID-19 vaccine at Kedren Community Health Center in South Los Angeles. “You have spoken into my life via the television for years. For years!”

Her words seemed to prove what Jones had just been telling me. That, as the well-known bishop and senior pastor of City of Refuge Church in Gardena, he was in a powerful position to help reverse the stubborn racial disparities that have, thus far, dogged California’s rollout of the vaccines.

As of Sunday, white residents had received 32.7% of the 5.7 million doses that had been administered statewide, compared with 16% for Latino residents, 13% for Asian residents and 2.9% for Black residents, according to new data from the California Department of Public Health. The rest went to people who identified themselves as other or multiracial or who didn’t state a race.

Jones wants more Black Angelenos to get vaccinated, as we are among the most likely to contract and die of COVID-19 along with Latinos.

“That’s why I’m coming forward,” he said. “I think it would be good for me to take the lead.”

I’ve spent enough time in Black churches to know the crucially important role they play in distributing accurate information to the public — not to mention in dispelling conspiracy theories. And although I’m not particularly religious, I also understand why Black people — long the subjects of medical racism — would trust the advice of a pastor who they’ve known for years over that of a doctor they just met.

The pandemic has forced churches across California to keep their doors shut for much of the last year. For some, that has meant losing loyal congregants who lack internet service and, therefore, have been unable to watch sermons online. For others, the shift to streaming solely on social media has allowed them to actually expand their congregations.

City of Refuge is one the churches that has grown and Jones has used the opportunity to speak to more people about the dangers of COVID-19 and the safety of vaccines. In fact, the biggest reason he wanted to get vaccinated was to set an example for his congregation of 20,000, and for the hundreds of others who also now watch him online every Sunday.

Too many members are reluctant to get vaccinated, he said, despite the risks they face. They insist that the vaccines are “evil,” he said, and that the coronavirus was manufactured and that Donald Trump had something to do with it.

“It’s just the same old conspiracy stories. There’s no proof for any of that,” said Jones, 71, who also happens to be the brother of model and actress Grace Jones. “So what I do is I go in and say, where’s the proof? Let’s talk reality.”

::

I’ll admit, I was somewhat surprised that Jones would choose Kedren Health, a relatively small vaccination site in one of L.A.’s most neglected neighborhoods, as the place to wield his considerable star power. But I shouldn’t have been.

The reputation of this mental health hospital that’s punching above its weight as a vaccination site has only grown since I was there in January interviewing director Dr. Jerry P. Abraham about his mission to get more doses to the many vulnerable Black and Latino residents of South Los Angeles.

There’s an almost cult-like following of fans now. If you think of the vaccination “super site” at Dodger Stadium as a chain restaurant, with service that’s efficient but inflexible, then Kedren Health would be a family-owned soul food restaurant, a place where the kitchen might run out of stuff from time to time, but everyone knows the service is always personal.

It’s one reason I decided to start volunteering here.

On my first day, the day Jones showed up, a staffer told me about woman who was so moved by Kedren Health’s mission of equity that, after being vaccinated, she started going door to door in South L.A., dragging her neighbors back to get vaccinated.

Many others, I learned, have become evangelists for the vaccination site among their Black and Latino friends and relatives.

Compton residents John and Pearl Samuels told me they heard about it from their daughter, who, in turn, heard about it from a friend. Louise Jackson of Inglewood, who arrived at Kedren Health with her husband, Keith, had a similar story. They had been trying for weeks to make appointments to get vaccinated without success.

“The only thing about it is that there’s not that many of us here,” said Louise Jackson said of other Black people.

Jones, who also heard about Kedren Health through a friend, agreed.

“We need to come,” he said looking around, “because the percentages are off.”

::

On Sunday morning, days after his vaccination, Jones stood behind the pulpit as usual, staring into a camera and searching for a way to get through to his most obstinate congregants watching on their screens.

“I’m opening with the mask,” he said, “because it’s important for us to still remember that we are coming out of a pandemic. They’re reopening very slowly. Don’t think that’s going to happen overnight. We still have months to go.”

He then talked about Rev. Frederick K.C. Price, the televangelist who founded the Crenshaw Christian Center megachurch in South Los Angeles. He died from COVID-19 on Feb. 12 after spending several days in the hospital. He was 89.

“We should pray for them,” Jones said of the Price family, “that the Lord will just put his arms around them and comfort them again. (It’s) one of the cornerstones of the churches in this city for years and years. He has blessed people all over the world. And we must pray for his family. That is a tremendous loss.”

Weeks ago, the city converted the parking lot of Crenshaw Christian Center from a COVID-19 testing site into vaccination “super sites,” hoping to provide more access for Black and Latino residents in hard hit South L.A.

It’s one step in the right direction. But there need to be more.

“The vaccine is out and things are changing, as we can see,” Jones said. “But at the same time, we have to continue to be careful, continue to follow the rules, because many people are still caught between taking the vaccine not taking the vaccine. And it’s going to be touch and go here because there’s so much distrust in our country, and so much distrust in the people who have been in charge for years.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.