California banned private prisons, immigrant detention centers. Will the law survive court?

- Share via

When California legislators voted to ban private prison contracts in 2019, advocates hailed the first-of-its-kind law as a victory for immigrants who they said have long suffered in facilities run by corporations that cut corners and provide substandard living conditions and medical care.

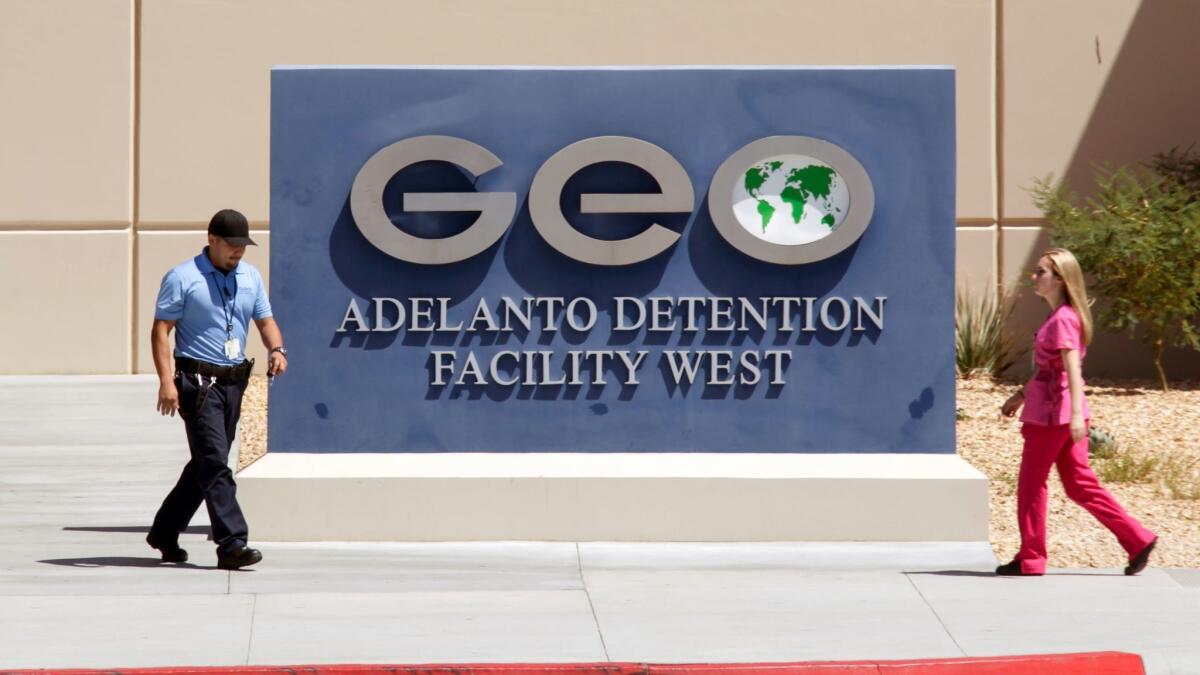

Not everyone saw it that way. GEO Group, a Florida-based private prison corporation, sued days before Assembly Bill 32 took effect Jan. 1, 2020, calling the law a “transparent attempt by the state to shut down the federal government’s detention efforts within California’s borders.”

The Trump administration quickly filed its own lawsuit with similar claims against the law, which prohibits new for-profit detention contracts and phases out current facilities entirely by 2028.

In October, a U.S. District Court judge in San Diego largely upheld the private prison ban, saying the state has the authority to protect the health and welfare of federal detainees held within its borders.

GEO Group and federal officials appealed that decision. Last week, lawyers now representing the Biden administration urged a panel of judges on the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals to repeal the law.

AB 32 will prevent the state from entering into or renewing contracts with for-profit prison companies after Jan. 1, 2020, and phases out such facilities by 2028.

Even as the battle over the law continued, private prisons were being depopulated because of the pandemic.

GEO Group leaders have started pushing to refill facilities in California that are at a fraction of capacity. The company sought to intervene in lawsuits over dangerous conditions at two facilities that led to COVID-19 outbreaks last year. Federal judges ordered the release of many detainees and blocked new transfers.

The Mesa Verde facility in Bakersfield, which has capacity for 400 detainees, now holds fewer than 30. And the Adelanto facility near San Bernardino, which can hold nearly 2,000 detainees, currently has fewer than 130. Because of guaranteed minimum detention bed quotas, Immigration and Customs Enforcement has continued to pay GEO and other contractors for thousands of empty beds.

In June 3 court filings, a lawyer for the company stated that the successful vaccination program at Adelanto had changed circumstances enough to safely begin moving toward pre-pandemic capacity.

“Since GEO is compensated for the use and operation of the Adelanto facility, capacity restrictions at Adelanto directly affect GEO’s economic interests,” wrote GEO Group lawyer Raymond Cardozo.

GEO Group spokesman Pablo Paez said the company plays no role in ICE’s detention decisions.

“We strongly reject the characterization that GEO is seeking to repopulate any of the ICE Processing Centers we operate on behalf of the federal government,” he said. “Our court filings exclusively seek to have the COVID-related operational restrictions match and reflect the most current data on COVID vaccination and case rates and the mitigation measures implemented at our facilities.”

California’s private prison ban would force the closure of seven privately run immigration detention facilities, which collectively have space for nearly 7,200 people. GEO Group operates most of them, three near Bakersfield and two near San Bernardino.

Weeks before AB 32 took effect, federal officials signed contracts totaling nearly $6.5 billion with GEO and the two other companies — CoreCivic, and Management and Training Corp. — that run California’s four private immigrant detention centers. The contracts have terms of 15 years, inclusive of two five-year extensions, ending in 2034.

Five days after Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the law, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials posted a solicitation on the Federal Business Opportunities website for at least four detention facilities around the state.

If AB 32 forced GEO to close its facilities in California, the company said, it would lose an average of $250 million a year in revenue over the next 15 years, plus the $300 million invested in acquiring and setting up those buildings.

If no privately operated detention facilities were permitted in California, there would in effect be one facility in the state that ICE could use to hold detainees: Yuba County Jail, which has 220 beds. The agency argued that the closures would force detainees to be transferred out of state, away from family and lawyers, while supporters of the law said ICE could instead use alternatives to detention, such as ankle monitors.

Last week, U.S. Rep. Norma Torres (D-Pomona) led 23 other lawmakers in sending a letter to Atty. Gen. Merrick Garland, urging him to drop the lawsuit against California. Outside the 9th Circuit courthouse in Pasadena on June 7, activists called for the same.

Private prisons are a multibillion-dollar industry in the U.S. and are currently operating in 27 states. Though the facilities hold 8% of all state and federal prisoners, the vast majority of immigrants detained for deportation are held in for-profit detention centers.

Shortly after taking office, Biden signed an executive order phasing out federal use of private prisons. However, the order doesn’t apply to immigration detention centers.

In November 2019, Kamala Harris, then a U.S. senator, was among the lawmakers leading a letter to Department of Homeland Security and ICE officials expressing concern that the hastily procured detention center contracts were an “apparent attempt to undermine the spirit of the new law before its effective date on January 1, 2020.”

“The Biden administration’s callous disregard for the issue of immigration detention is embodied by their decision to side with private prison companies in the AB 32 litigation and defend profits over human lives,” said Hamid Yazdan-Panah, advocacy director of Immigrant Defense Advocates, who has closely followed the AB 32 court battle. “When confronted by activists on the issue of detention, Biden said, ‘Give me five days,’ which he later said was a joke. No one is laughing.”

During the hearing, lawyers for GEO and the federal government argued that regulating federal functions such as immigration detention is beyond California’s authority.

“There is not a case we’re aware of which has ever upheld a restriction that is remotely like this one,” said U.S. Department of Justice lawyer Mark Stern, calling the law intrusive and extraordinary.

Banning private prisons prevents the federal government from “doing what is necessary to execute its duties,” Stern added.

Supporters of AB 32 argued that federal law doesn’t actually authorize ICE to contract out its detention functions to private companies. During decades of revisions to immigration law, they argued, Congress never explicitly authorized ICE to hire private companies for detention operations.

“This lack of authorization has been hidden in plain view for years, but the lawsuits over AB 32 have brought the issue to the surface,” said Jordan Wells, a lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California.

Wells said the Immigration and Nationality Act does authorize ICE to contract with state and local governments for detention operations. Under the same law, however, Congress authorized the U.S. Marshals Service to delegate detention responsibilities to “private entities.”

Stern dismissed that argument, saying that had there been any doubt, Congress never would have funded privately run detention facilities.

Other states have passed similar laws. Illinois banned private immigration detention facilities in 2019 to block the construction of a 1,300-bed facility outside Chicago. In April, the governor of Washington signed a measure banning for-profit prisons, which would force the closure of a 1,575-bed immigration facility. GEO Group sued the state last month.

AB 32 also banned for-profit prisons that hold people for criminal violations. Seven private facilities that housed California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation inmates have since closed, though three were repurposed as annexes for established ICE facilities under the contracts signed just before the law took effect.

But the law does not fully rid California of private prison companies. Private companies manage federal prisons and city jails, as well as substance abuse treatment centers, transitional housing and parole services. CoreCivic also owns the 2,300-bed California City Correctional Facility in Kern County, which wasn’t affected by AB 32 because the state manages the prison itself.

California Deputy Atty. Gen. Gabrielle Boutin said the law is about protecting Californians.

“These facilities create threats to the health and welfare of detainees,” she said. “There is a well-documented record of that.”

During the June 7 hearing, Judge Bridget S. Bade, a Trump appointee, took issue with the law’s exemptions, which allow for the use of private facilities to hold Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation inmates if necessary to comply with a court-ordered population cap. That cap, however, has not been met and the state already closed all of those private facilities.

Boutin said other exemptions, such as for school detention or detaining a shoplifter in a grocery store, differ significantly from criminal or immigration detention and don’t have the same record of health and safety violations.

The judge appeared unmoved by Boutin’s explanation.

“So minors, people with mental health issues, people in rehabilitation centers, halfway houses — California is not concerned about their health and safety if a private contractor is running those facilities, but they are if it’s a Department of Corrections facility or an ICE facility,” she said.

Sharon Dolovich, director of the prison law and policy program at UCLA, said that the shift in the center of gravity on the 9th Circuit could signal an ideological inclination toward protecting businesses that make their money performing public functions.

At the same time, GEO Group faces shrunken detainee populations and dissatisfied shareholders. Investors sued the company in September, alleging that leaders maintained ineffective COVID-19 response procedures that subjected halfway house residents to significant health risks and opened the company to financial and reputational harm by issuing misleading public statements.

“So it doesn’t surprise me that they’re pulling all the stops to defend their contracts in California,” Dolovich said, “because to lose here, given that they have a large percentage of their business in immigration detention, could really endanger the sustainability of their business.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.