How a racist myth about immigrants voting continues to fuel unproven claims of voter fraud

- Share via

For more than three decades, the racist myth has circulated around elections, often told in rich detail, of undocumented immigrants traveling poll to poll to vote illegally.

In some variations, they travel by bus. In others, a van, usually white.

Occasionally, the story goes, the perpetrators are caught, but usually not.

But the core of this canard remained generally the same as it spread out of California and into national politics.

The story has been used by political candidates, anti-immigration activists and election “watchdog” activists recruiting volunteers and seeking restrictions on voting. For national audiences, it has been invoked by right-wing provocateurs and broadcast by Russian trolls seeking to influence U.S. elections. President Trump falsely claimed that millions of immigrants living in the country illegally voted in 2016 and, separately, that hundreds of buses carried voters across state lines to cast ballots in the New Hampshire election.

In that same election year, the fable of the traveling voters appeared in Arizona, Louisiana and Pennsylvania. One account described voters only as Black and said they were driven into Alabama to cast ballots in a special election.

The vast majority of the stories targeted Latinos, and often in derogatory terms. In those ways, they are not unlike other bald fictions used in U.S. history to justify voting restrictions against immigrating Catholics, Irish and Chinese people, freed Black Americans and others. In the 1800s, for instance, arrivals from Ireland were accused of registering to vote as they stepped off the boat.

Conservative activists pressure election officials to drop people from voting rolls, claiming it invites massive ballot fraud in California

Documented cases of noncitizens voting in current times are isolated, election experts and prosecutors say. In Riverside County, where prosecutors in 2019 found one undocumented immigrant voting for more than a decade, investigators said there was no evidence to support allegations that such fraud is widespread or organized.

Racism plays an obvious part in why such stories continue to be repeated, said Mindy Romero, a political sociologist who runs the Center for Inclusive Democracy at USC. “We are more suspicious of people of color, even more suspicious if they are immigrants,” Romero said.

But the stories of vans of traveling voters contains so many dubious elements that believers must disregard reason as well as an understanding of voting security measures.

They do so, Romero said, because they feel something precious is at stake — their way of life, their understanding of democracy, or what the country should look like. The myth then becomes a tool others can use, whether to suppress the voting power of one group or rile up another.

“There’s a utilitarian aspect to allegations of voter fraud in general,” said Thomas Saenz, president and general counsel of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, based in Los Angeles. “It then supports voter suppression measures that are defended as ‘election integrity.’”

Latinos especially are targeted, Saenz said, because they are a growing electorate and because of relatively low voting rates.

“We have a lot more ground to gain in actually getting folks currently eligible to register and turn out” to vote, he said.

“Those are both, not coincidentally, dangerous to the forces that are trying to suppress them.”

::

The story of the traveling voters is particularly Californian — in one version the van is driven by a farmworkers union — and entangled with the state’s election watch movement.

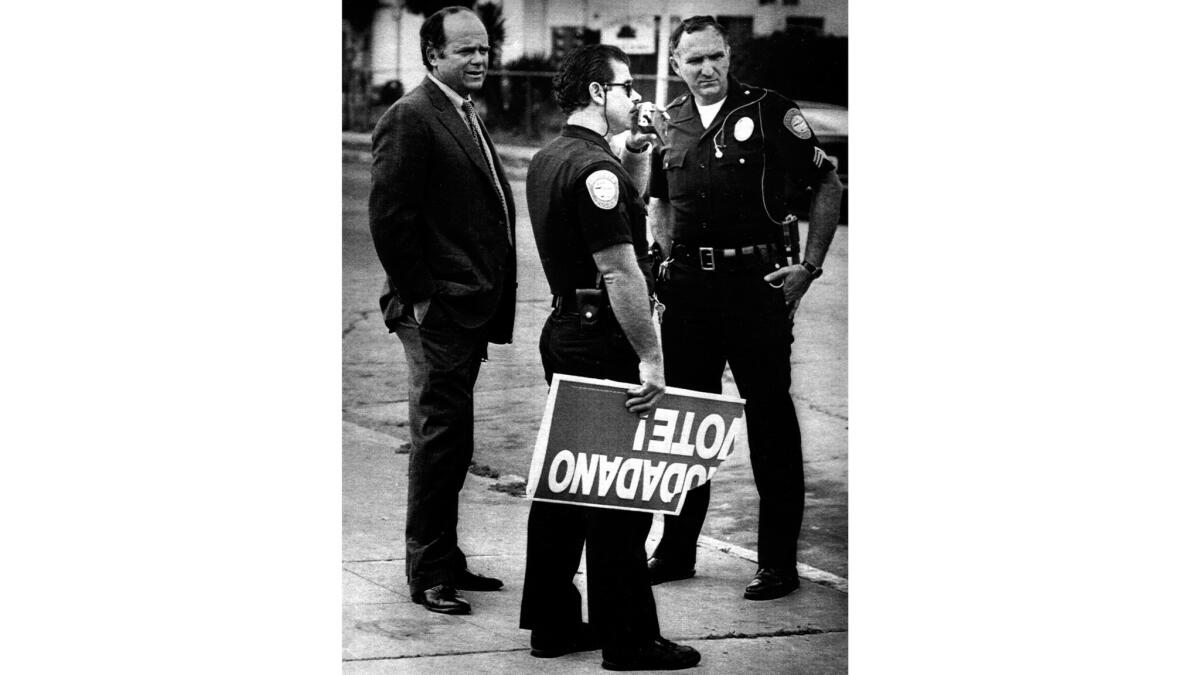

The earliest published reference found by The Times was in an infamous battle over a state legislative seat in 1988, when Republicans hired security guards to police the vote in Latino neighborhoods, holding up large placards that said “Non-citizens Can’t Vote!”

The Riverside County investigation illustrates the challenge authorities face when dealing with allegations of massive voter fraud.

“There seemed to be some concern about some allegations of voters going from precinct to precinct in vans,” the county election chief at the time said, confirming that Republican campaign officials had raised voter fraud concerns months prior.

Rudy Rios, a labor organizer, encountered the guards at his Santa Ana polling location.

“It’s offensive to me, because I should have the right to vote without being questioned or anything like that. Because I’m an American,” he said.

Republican leaders across the state denounced the security stunt, and the California Legislature a year later passed a law prohibiting uniformed poll observers.

But the victorious Republican candidate whose campaign helped arrange the security guards — Curt Pringle — went on to become Assembly speaker and mayor of Anaheim. There were calls for the county party chairman, Thomas Fuentes, to be removed from office, but at the first central committee meeting after the incident, attendees were handed “I ❤️Tom” stickers and an agenda item about ballot security was skipped.

::

Allegations of immigrant voter fraud were incorporated into the 1994 campaign for Proposition 187, a ballot measure to deny state services to those living in the country illegally.

After the campaign, one of the measure’s chief proponents — a former federal immigration officer — launched a task force to hunt for electoral fraud. A legislative consultant took up the cause, forming the Institute for Fair Elections, which to this day seeks to have election officials hunt for and remove noncitizens from voter rolls.

The roving van story circulated by word of mouth in poll watch circles. In a 2019 video-recorded meeting in Placer County, a poll observer told of hearing secondhand about a migrant worker rousted out at 6 a.m. to spend the day going poll to poll, in a van driven by the United Farm Workers union.

“Every two hours, they would stop, had coffee and doughnuts at rest stops and parks, gave him lunch, gave him dinner,” the poll observer recounted, according to video of his comments. “He didn’t get back home until 9 o’clock at night. When he reached in his pocket, he pulled out the little tags that said, ‘I voted.’

“He counted them. Nineteen times, he voted that day.”

Those in the audience gasped.

The meeting was a presentation for the Election Integrity Project, another California vote watch group. Its vice president tells her own version of the van story — set in San Diego County in 2010.

“They had vans coming across the border,” Ruth Weiss said on a 2020 podcast with California Republican Party Secretary Randy Berholtz, a longtime friend and supporter of the Election Integrity Project. Both he and Weiss declined to be interviewed.

“Everybody jumped out with a vote-by-mail ballot and went in and submitted it. Got back in the van, were handed another ballot. They went like three times to the same polling place,” Weiss said. “And then they went to the next polling place and did the same thing.”

Like most other renditions of the van story, there is no explanation for how witnesses at one location knew what happened later and elsewhere, or how they knew the vehicle’s occupants were not citizens. Transporting voters to the polls is not only legal but a common service.

Weiss said the witnesses were partisan observers: one Republican, one Democrat. “In fact,” she said, “they videotaped it.”

Weiss said the witnesses turned in their video to the San Diego County district attorney’s office, which she said notified the fraud division of the secretary of state’s office. When the observers later asked what came of the incident, she said, they were told, “We don’t remember receiving anything like that. … It just got buried.”

A spokeswoman for the San Diego County district attorney’s office said staffers had no recollection of reports of a border-hopping van of voters. Nor did the secretary of state’s staff, said spokesman Joe Kocurek. Both said the story was so remarkable that they believed workers would remember it.

::

The traveling van story didn’t go big until the 2016 presidential campaign of Donald Trump.

Stories of the van were spread by conservative satire sites like the Last Line of Defense, repeated by other partisan sites without the caveat that the content was a fabrication, then championed by individuals on their social media accounts as if fact.

Russian trolls seeking to disrupt the U.S. electorate repeated the theme, according to a Clemson University collection of posts by Twitter accounts reported to Congress as being tied to the Kremlin.

“Dirty ground game n #nevada , bused in #illegals from CA to urge #Hispanics to vote for #HillaryClinton ! #NeverHillary… #TrumpForPresident” tweeted the account “GarrettSimpson_”, while other alleged troll accounts promoted a false story of mass arrests of noncitizen voters in California.

On the day of the presidential election in 2016, conservative provocateur James O’Keefe posted on Twitter video of himself tailing a blue van in Philadelphia, saying it was “busing people around to polls.” He promised to tell followers about “some people doing some improper things,” according to a chronicle of O’Keefe’s posts by Talking Points Memo.

Trump jumped in. “In addition to winning the Electoral College in a landslide, I won the popular vote if you deduct the millions of people who voted illegally,” he tweeted in late November 2016.

::

One episode in Orange County did reveal that hundreds of noncitizens had been improperly registered to vote.

The allegations of voter fraud were made by U.S. Rep. Bob Dornan, a Republican, after he was unseated by Democrat Loretta Sanchez. The claim triggered an investigation by a U.S. House committee, which obtained access to federal immigration records. The committee claimed to find 624 improperly registered voters, not enough to affect the outcome of the election, and most of them were U.S. citizens by the time they voted.

The Santa Ana chapter of a Latino empowerment group, Hermandad Mexicana Nacional, running a federal citizenship program, had handed clients voter registration forms as they completed immigration screening but before they were sworn in as citizens. An Orange County grand jury declined to bring criminal charges against Hermandad, and nearly 750 residents had their premature registrations canceled.

Rosalyn Lever, who worked in the Orange County registrar of voters office from 1972 through 2002 and rose to become head of the office, has remained adamantly nonpartisan, continuing to register with “no party preference” nearly two decades into retirement. Lever credited both political parties with “always trying to pull some kind of shenanigans.”

Even so, she said, “I gotta tell ya: Not one single election ever went by, when I was at the helm, without the Republicans calling in and saying there were white vans taking illegal people to vote.

“And I mean, I was there for 30 years and there was never such a thing.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.