- Share via

In the basement of Reign Salon in Antioch, a brick wall is a reminder of a dark past.

More than a century ago, Chinese people built tunnels under the city because they were forbidden by law from going outside after sundown.

Then, white residents burned Chinatown to the ground.

Today, few traces of the old Chinatown remain — some tunnel entrances such as the one in Reign, wood pilings in the San Joaquin River that were the foundations of houses.

Many people strolling in the Bay Area city’s quaint downtown, or getting their hair cut at Reign, are unaware that a Chinatown once stood there.

Antioch officials aim to change that, starting with a dramatic gesture.

First, the City Council apologized to all early Chinese immigrants and their descendants.

“An apology for dehumanization and injustices cannot erase the past, but admission of the wrongs committed can speed racial healing and reconciliation and help confront the ghosts of the past,” the council said in a resolution passed unanimously in May.

The council will also create a Chinatown Historic District and fund murals and museum exhibits commemorating the city’s Asian history.

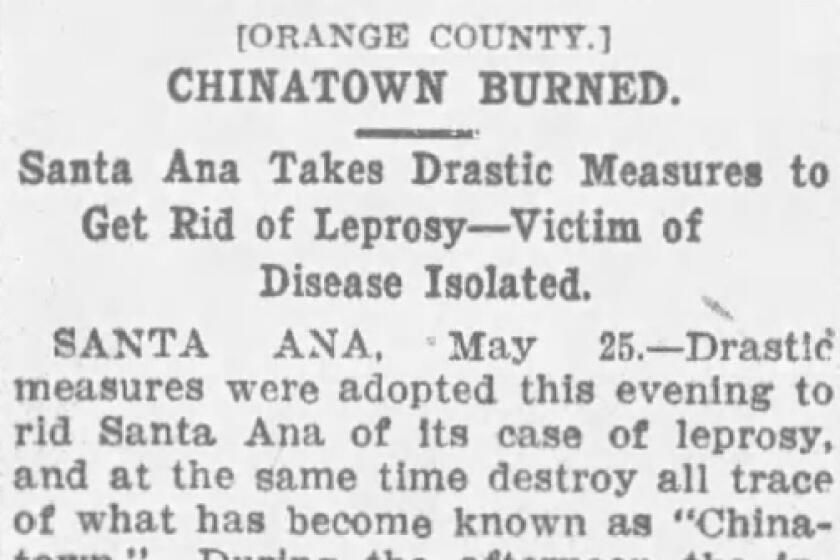

Antioch is one of many California cities, including Los Angeles and Santa Ana, where white residents lynched Chinese people or burned down their neighborhoods in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Amid the racial reckoning after the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis and a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes during the COVID-19 pandemic, Antioch is the first city to issue a formal apology.

“It was so painful to watch the news, and I kept thinking to myself, ‘It’s not enough to say we stand in solidarity with this group or that group,’” said Mayor Lamar Thorpe, who spearheaded the effort. “That’s what everybody hears. We need action.”

For Thorpe, 40, who is Black and was raised by a Mexican American family in East Los Angeles, racial injustice is deeply personal.

Nearly a decade ago, on a driving tour of the city, former Mayor Don Freitas gave him a history lesson about the long-ago Chinese inhabitants as they passed Waldie Plaza, a downtown public square within the old Chinatown boundaries.

Thorpe, who refers to himself as “Blaxican,” wondered why the past was not more openly discussed in the racially diverse city of about 110,000, which is 33% Latino, 28% white, 22% Black and 12% Asian.

He was elected mayor in November, following a summer of protests after the police killing of Floyd, a Black man.

The next month, Antioch police killed a 30-year-old man suffering from a mental health crisis. Thorpe proposed a slate of policing reforms, which the council passed in February.

As attacks against Asian Americans continued and six Asian women were fatally shot at Atlanta-area spas, Thorpe decided it was time to address Antioch’s history of violence and discrimination against Chinese immigrants.

“I got elected during the Black Lives Matter wave, and I feel our city that drove the Chinese Americans out over 100 years ago needs to confront what happened, and we need to make amends,” he said.

An apology and commitment to “rectify the lingering consequences” goes a long way, said Andy Li, president of the Contra Costa County Community College District and the first Chinese American elected to its board.

Efforts to obtain an apology from the federal government for the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which prohibited Chinese immigration, resulted only in expressions of “regret” from the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate, Li said.

“Just like they want to make a historic district, this is a historic moment,” Li said. “Finally, we have something significant.”

Arellano: A racist mob burned Santa Ana’s Chinatown to the ground. It still serves as a lesson

Too few of us see the recent anti-Asian madness for what it is: a plague that can only end when non-Asian Americans see the blind spot within us.

Chinese immigrants arrived in Northern California during the Gold Rush. Some later helped build the railroads.

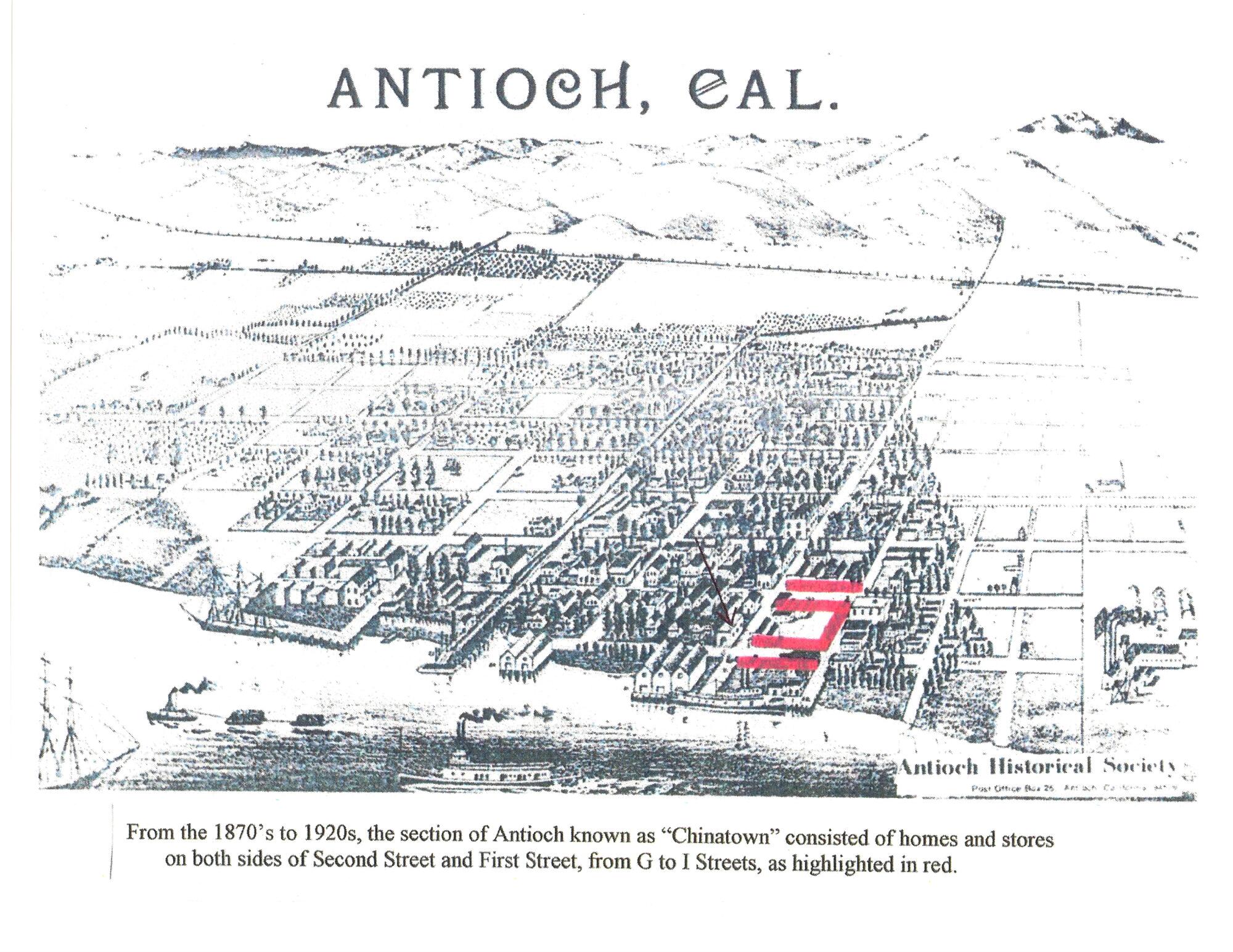

In Antioch, they established a small Chinatown on 1st and 2nd streets with storefronts selling noodles, herbal potions and laundry services.

In 1851, a county law went into effect that prohibited Chinese people from walking the streets after dusk, according to the Antioch Historical Society.

The immigrants dug tunnels so they could move around at night.

“They couldn’t be on the streets, so they found a creative way out by going below the streets.” said Dwayne Eubanks, the historical society’s president. “The gravity of what went on cannot be forgotten. I can understand why the mayor did what he did. We need to move forward.”

In May 1876, tensions between white residents and Chinese immigrants came to a head.

According to newspaper accounts from the time, some young white men had contracted diseases from Chinese prostitutes.

Angry citizens ordered the Chinese to leave town, and the immigrants departed on boats.

But that was not enough. People set fire to Chinatown.

“Today the remaining houses have been removed and Antioch is now free from this degraded class,” the Los Angeles Evening Express said on May 2, 1876.

“Antioch has now no Chinese or Chinatown,” the Sacramento Bee declared. “The Caucasian torch lighted the way of the heathen out of the wilderness.”

After the destruction of Chinatown, Chinese people still occasionally made a life in Antioch.

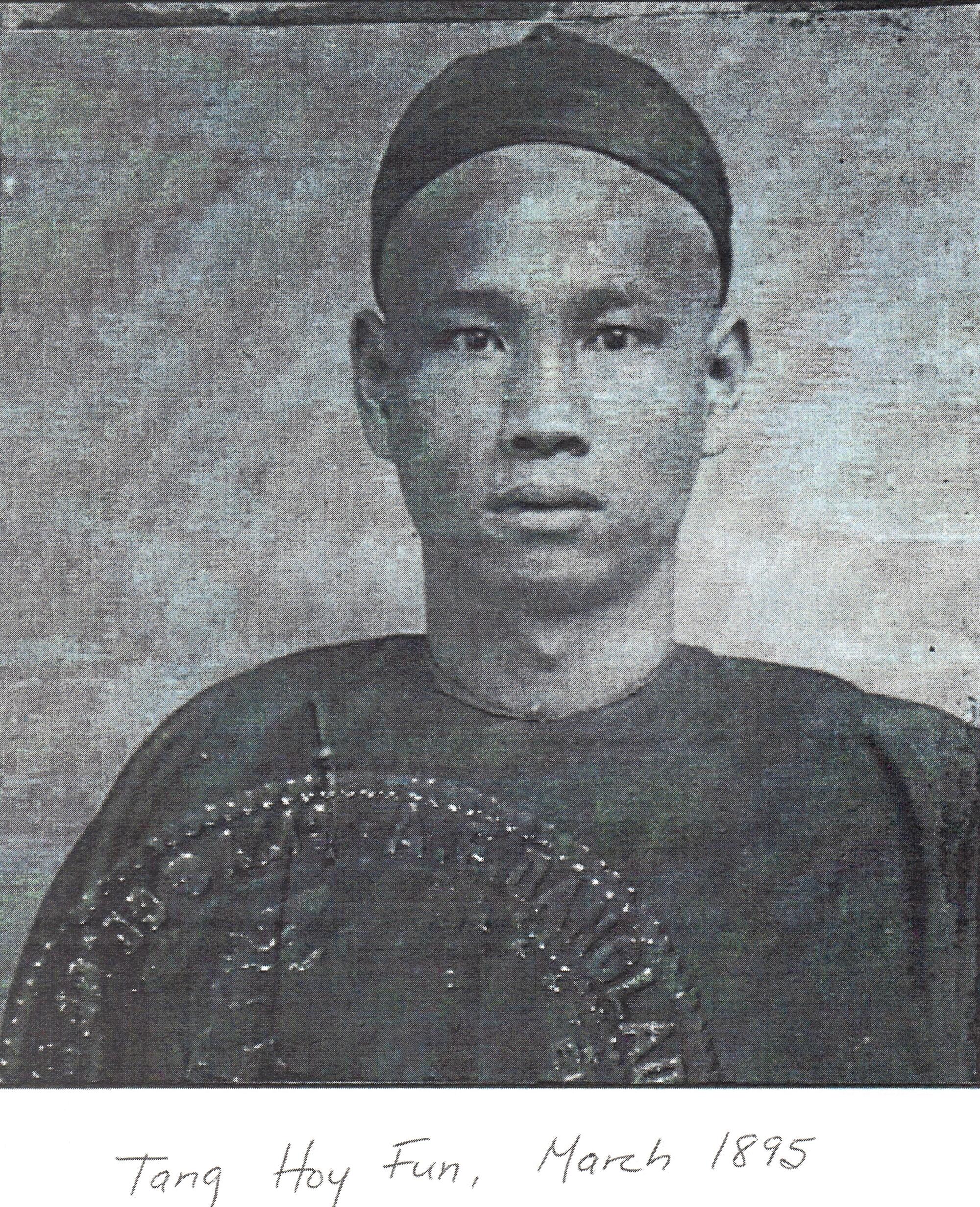

A work permit from the Antioch Historical Society’s collection, labeled “Tang Hoy Fun, March 1895,” includes a photo of a serious-faced young man in a skullcap and traditional Chinese gown.

A man known as Ah Young grew vegetables and sold them door to door in the 1920s, also shipping his produce to San Francisco and Stockton, according to the historical society.

Another Chinese man, Lew Hing, owned a fruit canning company during the same era.

When the Palace Hotel was demolished in 1926 to make way for a new theater, a section of the Chinese tunnels was uncovered, according to the historical society.

The tunnel remnants, in the basements of Reign and other downtown businesses, including a cafe, are a reminder of the hard lives that Chinese immigrants led long ago.

“Customers are drinking coffee and tea in the same room where people hid from their fellow residents. Imagine that,” said May Hong, a Chinese American secretary from San Jose who visited Antioch after reading about the city’s apology online. “When I told my relatives about the earlier discrimination, they were grateful to hear that public leaders are taking steps to say sorry.”

The Antioch apology highlights the similar histories of other California towns, said Laureen Hom, an assistant professor of political science at Cal Poly Pomona who is writing a book on Los Angeles’ Chinatown.

“The designation shows us that there were so many Chinatowns springing up,” she said. “We don’t know where they all were — yet we should try to find out more to preserve them.”

In Los Angeles, Chinese immigrants lived along what was then called Calle de los Negros, east of Los Angeles Plaza.

In 1871, police officers and a civilian named Robert Thompson responded to a shootout among Chinese men, according to the Los Angeles Public Library. Thompson was killed.

Residents rose up against the Chinese, hanging them at a wagon shop in front of a crowd, according to the library. Nineteen Chinese men were lynched.

In the 1930s, the old Chinatown was razed to make way for Union Station. The Garnier building on Los Angeles Street, which houses the Chinese American Museum, is all that remains.

A group of Chinese Americans bought a vacant rail yard and turned it into today’s downtown Chinatown, centered on Broadway and Hill streets, in 1938.

Later, immigrants from Taiwan and Hong Kong settled in the San Gabriel Valley, creating a suburban Chinatown.

As vaccinations picked up and case counts dropped, Valley Boulevard has slowly come back to life. Locals are starting to gravitate to their favorite noodle eatery or dim sum diner.

The next step for Antioch, after the apology by city officials, will be to hire a consultant for the historical displays, Eubanks said.

He envisions text and images to accompany a self-guided tour of the old Chinatown that visitors can access with a QR code.

C.C. Yin and his wife, Regina Yin, donated $10,000 to establish the historical district.

C.C. Yin, the founder of the grass-roots Asian Pacific Islander American Public Affairs Assn., is an immigrant from Taiwan who worked as a civil engineer before purchasing 26 Bay Area McDonald’s locations.

“We should move away from the intimidation and fear of the past to something stronger,” Yin said. “We want to unite not just Asian Americans but all Americans.”

Freelance photographer Mengshin Lin and Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.