Cal State students failing, withdrawing from many required classes at a high rate

- Share via

California State University students are failing or withdrawing at high rates from many courses — including chemistry, calculus, English and U.S. history — prompting renewed efforts for systemwide reform.

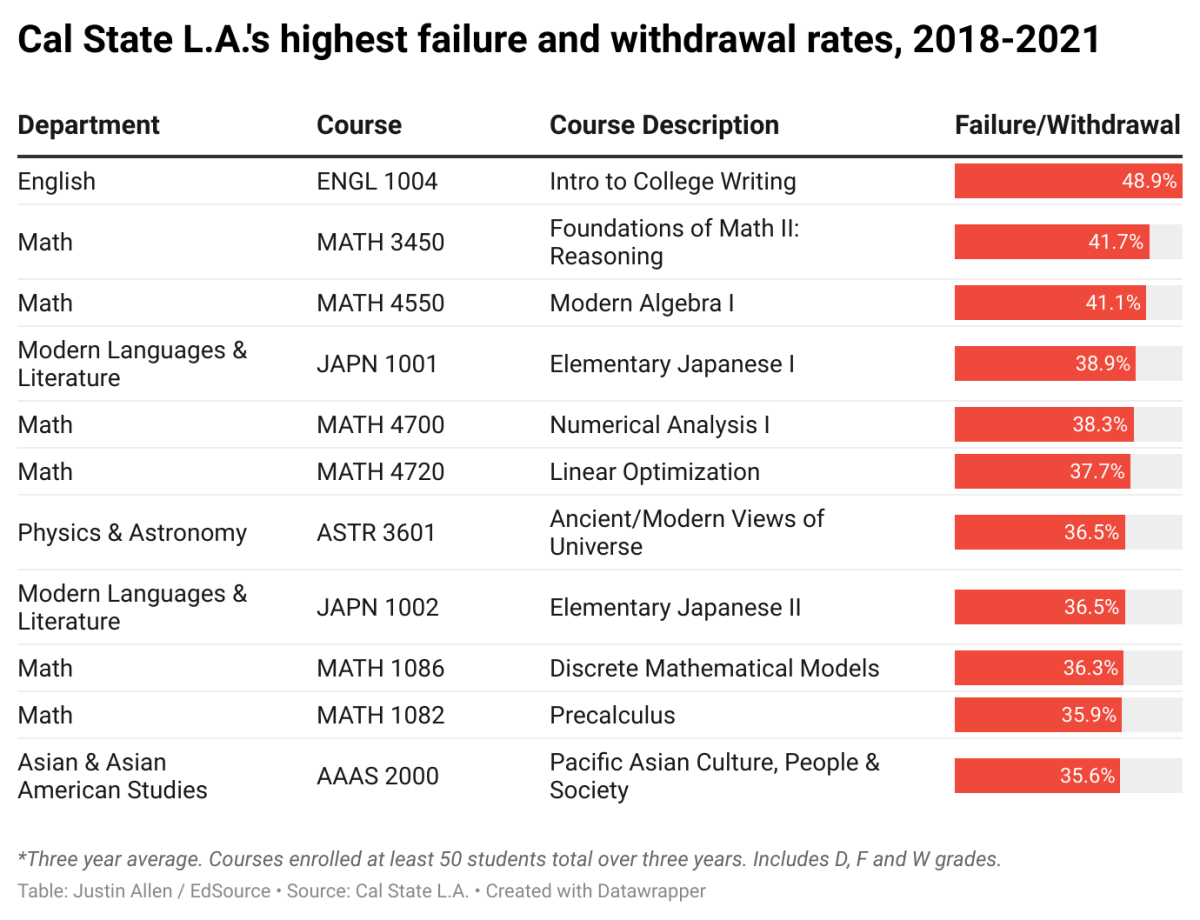

New attention is being placed on classes that for years have shown failure or withdrawal rates of 20% or more — sometimes reaching as high as half the students. Efforts to overhaul the courses and improve teaching are now seen as a crucial way to help more students pass and graduate.

For example, more than a third of Sacramento State students in some physics, economics, computer science and anthropology classes failed or left those courses. At Fresno State, the same was true in some math, chemistry, criminology and music courses.

When more than 20% of students in a class receive a D, F or withdraw, that course is considered to have a high “DFW rate,” in university parlance. Generally, course rates are averaged over three years. Cal State Los Angeles, for example, reports that about 11% of all of its undergraduate classes have high fail rates. Statistics are close to that for the Fresno and Sacramento campuses.

Officials said the problem exists across all 23 campuses.

CSU reported 686 high failure courses systemwide last fall with enrollments of at least 100. Campus administrators, however, are looking at smaller classes too, signaling that the problem is likely to be more widespread. Just three campuses, Fresno, Los Angeles and Sacramento reported a total of 453 high failure courses.

Challenging course material, ineffective teaching and unprepared or overwhelmed students contribute to the rise in high failure/withdrawal rates, experts say. Failures in these courses and repeated attempts to pass them can add semesters to students’ time on campus because many of the courses are required for their majors. Worse, failing a class can send students into a tailspin that leads to abandoning majors or dropping out altogether.

COVID-19 forced schools to shift to online learning. At CSU, it’s sticking around in what will be a new normal.

CSU Chancellor Joseph I. Castro has put a priority on reducing those high failure and dropout numbers at all campuses.

“It’s our goal to make sure that every student that we admit to the CSU has the full opportunity to succeed, to thrive. And it’s about providing the support necessary for them to do that,” Castro said.

Across the CSU, officials say new efforts are aimed to help more students pass these courses. More classes are being overhauled, teaching improved, tutoring and supplemental instruction expanded — all to propel students toward graduation. Among the successes: A recent reform of mechanical engineering classes at Cal State Los Angeles cut failure and withdrawal rates in half, from 32% to 16%.

Isaac Alferos, president of the systemwide California State Student Assn. said the group looks forward to working with administrators and faculty “to identify solutions... understanding that there is not a one-size-fits-all solution.”

Officials say that getting more students to pass these classes is key to the university’s plan to significantlyimprove graduation rates across all campuses and ethnic groups by 2025. The initiative has shown progress since it began in 2015, but more is needed to meet its goals. Recent statistics show that 31% of all freshmen graduate in four years and 62% in six, with systemwide targets of 40% and 70%, respectively.

Arecent report by a graduation initiative advisory committee of faculty, staff and students urged the CSU trustees to push for improved pass rates, with an emphasis on helping Black, Latino and low-income students pass these targeted classes. The trustees are expected to discuss the issue next month.

Particularly in some science and math courses, Blacks and Latinos on average show significantly higher failure rates than white and Asian students. For example, at Sacramento State’s college algebra, Latino students’ DFW rate was 36%; 33% for Black students; 23% for white students; and 18% for Asian students.

The directive is the largest of its kind in U.S. higher education and would likely take effect this fall after the FDA formally approves the vaccines.

“While earning a non-passing grade in a course can present a challenge for all students, the interruption and possible impact on time to graduation for students of color is often disproportionately negative,” the report said.

At Fresno State, where Castro previously was president, he had some success in improving graduation rates but that campus still shows 11% of all its courses with high DFW statistics.

It’s unclear whether the switch to remote learning during the pandemic affected course failure rates. Some classes showed worse results and others did better compared with previous in-person teaching.

Meanwhile some courses have shown improvements credited to changes initiated before the health emergency.

For example, Cal State Los Angeles overhauled five high enrollment courses with the steepest DFW rates, often over 30% of students. Those included basic accounting, chemistry, computer science and economics. After some success, the program is expanding to 30 more courses, officials said.

In mechanical engineering, 32% of the students had failed or withdrawn in 2018. Then, the course was redesigned to focus more on mastery of skills than memorization. Students were offered more frequent tests with four chances to pass them. Most lectures were switched to online recordings while classes mainly became work sessions, divided into groups by achievement levels. Extra tutoring was available.

As a result, officials say, the failure and withdrawal rate was cut in half by last fall, and faculty insist the material was not watered down. Professor Mathias Brieu said the redesign has mainly helped students who were close to a passing C but unable to reach it.

The reworking “has completely changed the atmosphere and our relationships with the students,” Brieu said. “There is a real connection now.”

The four other courses all showed improvement by fall 2020. However, the accounting and chemistry classes still had DFW rates of more than 20% while economics and computer science moved below that threshold.

Michelle Hawley, Cal State Los Angeles’ associate vice president and dean of undergraduate studies, said she is pleased with the improvement but recognizes the need for more. “I’m not happy with any numbers short of 99.9% pass rate and zero equity gap,” Hawley said, referring to gaps in failure rates among racial and ethnic groups.

The 23-campus system awarded nearly 110,000 baccalaureate degrees this spring, an all-time high for the California State University, and continues to make steady progress toward its 2025 graduation goals.

Faculty are concerned they will be pressured to lower standards and inflate grades. But Castro insisted that improvements can be achieved without watering down classes. “It’s about maintaining high standards,” he said.

Throughout the CSU, professors of courses with high DFW rates are being urged to reconsider teaching methods and possibly retraining. Administrators insist this is not done threateningly.

Some faculty, while supportive of helping more students succeed, are worried that untenured and part-time professors in particular could be pushed by their departments to raise grades. The graduation initiative “has created intense pressure to reduce fail rates so that students can graduate, and to reduce the impact of bottleneck classes,” warneda report issued last year by a committee of Fresno State’s Academic Senate. Although the report showed no evidence that the recent initiative is causing grade inflation, the authors expressed concerns about a possible “lowering of academic standards and grade inflation.”

Jeff Gold, the CSU system’s assistant vice chancellor for student success, denied there was any pressure to pump up grades. “That couldn’t be further from the truth,” he said.

He noted that the courses with the highest failure rates now tend to be clustered in the sciences and math, although U.S. history, which requires a lot of reading, has worrisome failure statistics too. Despite efforts, DFW differences may persist among campuses and between humanities and science courses.

“Our goal is not to focus on absolute numbers, but rather to bring people into the fold about how they can improve curriculum, how they can improve the support of their students so that more of them are successful,” he said.

EdSource is a nonprofit journalism website covering education issues in California.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.