‘The Loneliest Americans’: A conversation about Asian Americans and race with Jay Caspian Kang

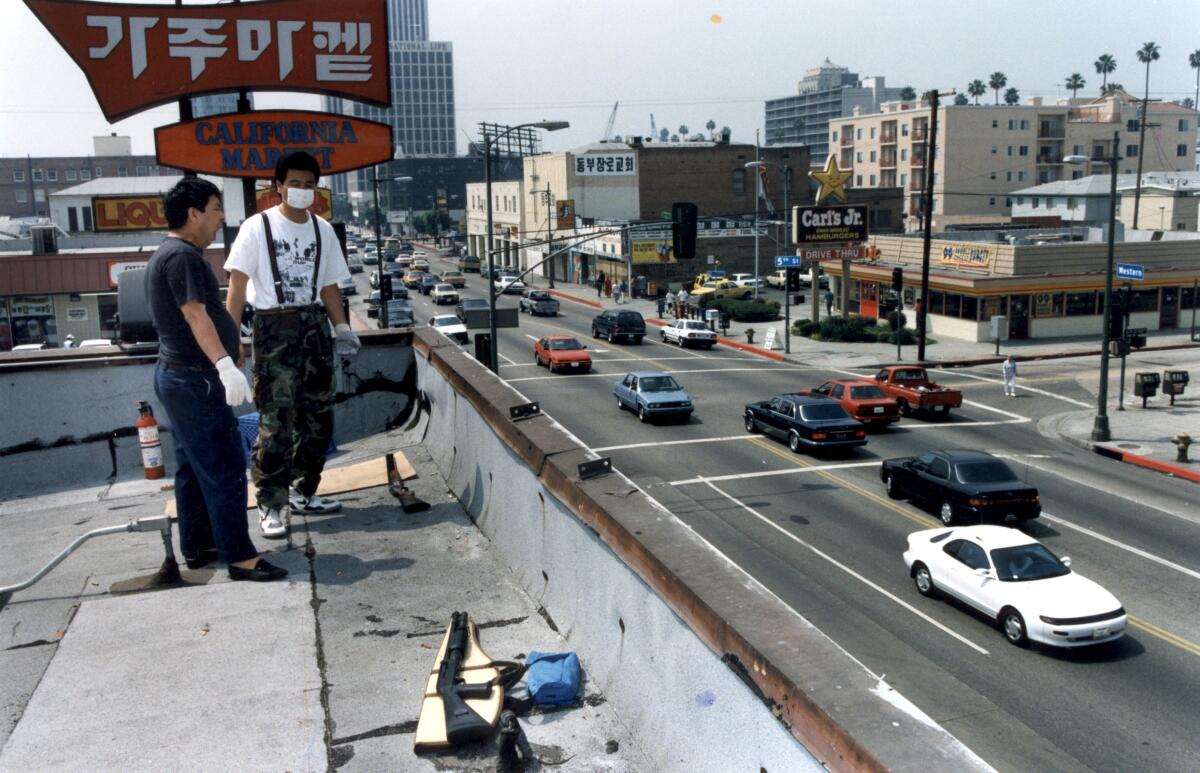

In 1992, a Korean man named Richard Rhee was photographed on the rooftop of California Market, a cellphone in one hand and a Colt .380 in the other.

The photograph captured one part of the traumatic soul-searching that Korean Americans began after the 1992 uprisings. Rhee was one of dozens of armed Korean men who patrolled the rooftops of Koreatown after the Los Angeles Police Department abandoned the neighborhood to rioters and looters.

For author and journalist Jay Caspian Kang, the photo of the rooftop of California captured the moment that Korean Americans realized that, “America would never accept them as white,” he writes in his new book, “The Loneliest Americans,” which examines the history and modern political identity of Asian Americans.

“The questions of identity that would plague their children meant nothing to them. They weren’t Asian Americans or Korean Americans or ‘Not Black,’ but Korean people in America,” Kang writes in the book.

Kang has been my friend for the better part of a decade. I began to follow his writing in 2012, when there were vanishingly few Asian American writers on the scene, and even fewer Asian American writers willing to take on Asian American topics. I first met him when he was speaking on a panel at the Japanese American Museum downtown about the time ESPN used the word “Chink” in a headline about a sports story featuring Taiwanese American NBA player Jeremy Lin.

As per usual, Kang had a surprising take that made some people angry, but also forced the conversation into a new area. As the audience warmed to the topic and began to discuss other incidents of anti-Asian racism, Kang interrupted. He said that he could understand the mistake and it was highly unlikely that the headline writer was trying to purposefully express anti-Asian sentiment.

I’ve been a fan of Kang’s writings on Asian Americans over the years because truthful discussions, especially about race, usually require pissing some people off. And Kang has always been willing to ruffle feathers in favor of saying something honest. He may write something that makes you angry, but he never holds himself above reproach. Some of the most searing lines in his new book are reserved for himself.

These days, the rooftop of California Market has been renovated into a contrastingly bucolic space with a playground and attractively potted succulents. A thriving food court featuring the latest in Korean street food trends now serves the space, which is popular with families and influencers.

You could see the space as a rudimentary metaphor for how far the Korean American community has come in the United States. But to Kang, it’s an example of how Asian culture, rather than Asian American culture, is still shaping our perceptions of Asian Americans.

“A lot of the growth and sophistication of the Korean American community is not coming from Korean Americans. It’s these cultural products coming over,” Kang said.

We sat down to talk about his new book, his family and Asian American political identity.

Why did you want to write this book?

It started out because I’ve been writing about Asian people for about 10 years. And I don’t think I have all the answers to everything. But I’ve been writing about this stuff long enough that I’ve become extremely opinionated about it, which to me means that it would be useful to write these thoughts down, in the most well-written and maximalist way I can. I thought about, “How do I present these thoughts in a forum where a lot of people will engage in it in a good-faith way, and argue with me about it?” I would like for people to argue with me and disagree with me. I don’t know if I succeeded or not, but that’s the thinking behind it.

What do you hope to achieve?

Over the last few years, I started to feel like Asian American identity, as a broad concept, the way it’s practiced in the academy and in the media, is an impediment to the goal of cross-racial solidarity and political belonging. It preferences a type of narrative that I had also preferenced earlier in my career — the narrative of people like me: second-generation, growing up experiencing poverty but with educated parents and upwardly mobile.

I thought this book could be like an intervention to that. Asian Americans have the largest income disparity within a group. There are tons and tons of poor Asians who are undocumented. But Asian American politics largely fails to address that. Rebuilding our political identity around solidarity with these people, I think that would lead to a better case for solidarity with other races. What we have now is a lot of bamboo-ceiling politics. A lot of Asian Americans access race through the lens of white liberals, and I just don’t think that’s very effective.

Upwardly mobile Asian Americans are creating a political identity that only benefits them. Sure, you want to stop being confused with your co-workers, for the delivery boy. But that isn’t a political identity. But I don’t think we will find a radical politics of our own through identifying microaggressions. The reactionary right-wing Asians, the anti-affirmative action Asians, I don’t agree with their politics, but I do think they come out of a sense of real desperation for political representation.

In the book you include one of your mother’s translated blog entries, and it turns out she is an incredible writer. This line describing what it was like moving to a place with a foreign language stuck with me: “One day, my language, abruptly severed in a foreign land, became sealed off inside of me, where it suffocated, and in the deafness of insensibility, I was absolutely lonely. To save my dying mouth, ears, head, heart, smile, tears, frisson and skin, I frantically became a child again to relearn the burbling of English.” What does your mom think of your writing?

I have no idea. She seems very uninterested most of the time, but when I make some sort of provocative argument, it piques her interest more. Her blog has a small and very loyal readership. She’s very uninterested in my relative success and very against bragging about any of her kids. She’s actually really interested in how our generation and younger Asian Americans will navigate belonging in this country. She thinks that what I should do as a writer is to help people with that process.

In the book, you attack the perception that Asian Americans have or will at some point achieve whiteness. There’s a lot of original reporting about the politicization of Asian immigrant communities in New York City, which you include to show that presumptive whiteness had very little, if anything, to do with immigrant success or motivations. Why did you think that was important?

We need to just be honest about who these people are. We should think about them if we want to make a coherent Asian America. We can’t think about them as people we want to sweep under the rug. I think that the more you focus on the people who actually need help, the more moral clarity you have and natural pathways for solidarity with other races emerge. That’s the underlying drive for these types of politics — they have to be about helping people who need help, not about “Why don’t I personally have a better job.” There can be a foundation of Asian American politics that is essentially materialist and economic in its concerns.

I’ve mostly agree with your conclusions about the state of Asian American politics. But I find myself feeling more sympathetic than angry at other Asian Americans making these political choices, even the selfish ones. So last question: Why are you so mad?

I am not angry at Asian Americans who go about their lives and try and make sense of their strange place in their country. I’m not angry at those people and whatever conclusions they’ve come to. I have a great deal of sympathy for that.

I am mad at upwardly mobile wealthy East Asians for creating a politics that benefits them. There is an Asian American elite that takes scraps of actual radical politics and applies it exclusively to their own lives, which are generally very privileged. That, I do blame people for, and think that we should change. It’s the refusal to call it what it is. That is a type of political selfishness that wants to have it every single way possible. If it ends up being the sum of my life’s work to piss those people off, then I’m fine with that. I think we all have a responsibility to be a class traitor, to be better than that.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.