Q&A: Gov. Newsom talks about his children’s book to help those, like himself, with dyslexia

- Share via

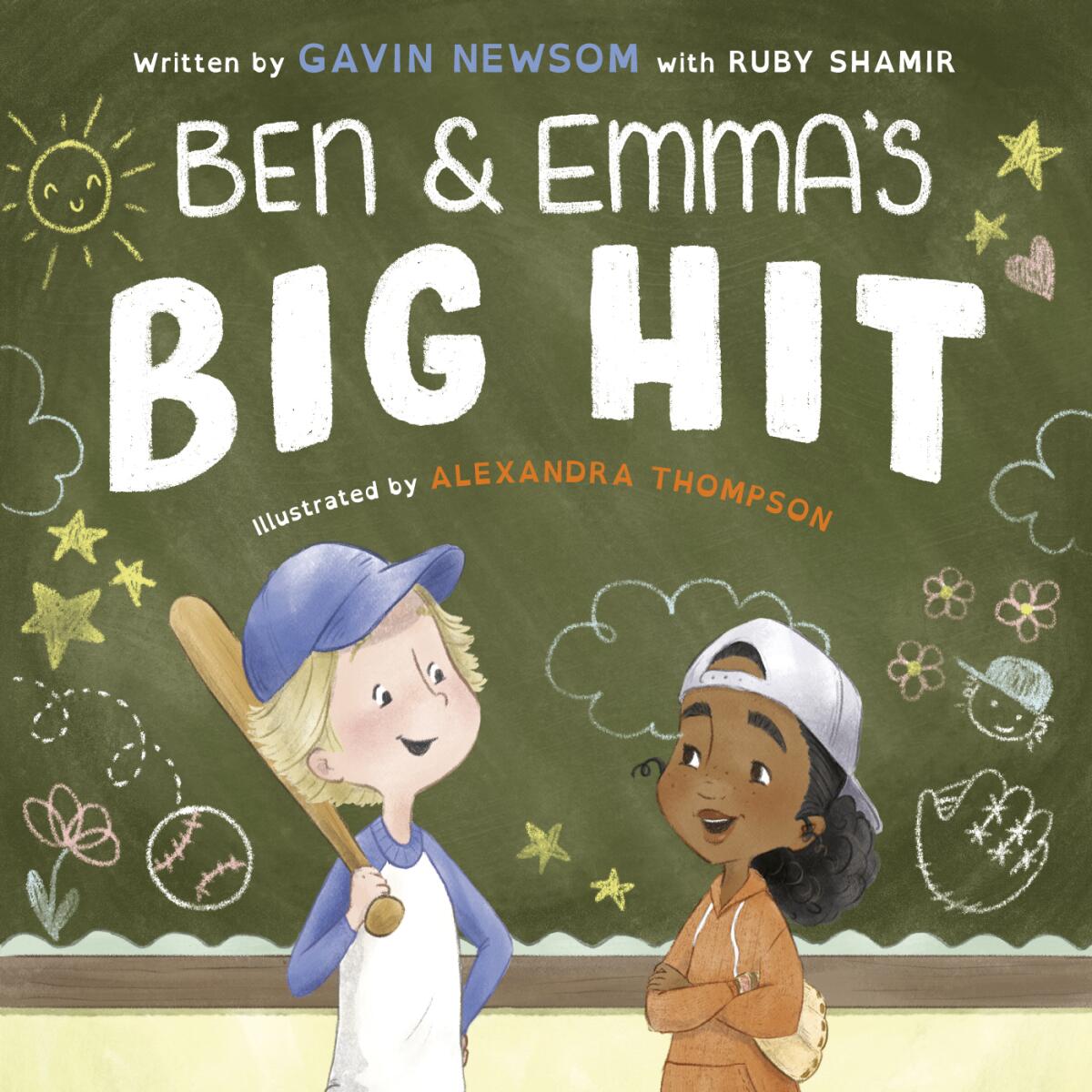

SACRAMENTO — Gov. Gavin Newsom has struggled with dyslexia since elementary school. Now he’s telling his story through Ben, the baseball-loving protagonist of his new children’s book who has a tough time reading, too.

“Ben & Emma’s Big Hit,” which goes on sale Tuesday, parallels Newsom’s experience with dyslexia, which he learned he had in fifth grade.

The 54-year-old governor said parenting his own children, who also have learning issues, inspired him to work with Philomel Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House, after noticing a lack of picture books designed for young dyslexic children learning to read.

Ben’s character draws on a young Gavin, who excelled on the baseball field but whose learning issues left him anxiety-ridden in the classroom, perspiring at reading time and feeling like he wasn’t as smart as other kids.

Ben’s teammate Emma fakes her reading abilities by toting around the “biggest, fattest chapter books,” which the governor said is derived from his own attempts to cover up his learning issue.

The book includes other more subtle nods to Newsom’s life, such as a page illustrating the school hallway that shows classroom number 5902, the date the governor’s mother, Tessa Thomas Newsom, died: May 9, 2002.

Newsom credits his mom with never giving up on him and said he now has a deeper understanding of the difficulty she experienced as a parent watching his own children cope with learning challenges.

In the story, Ben and Emma’s teacher confesses that she couldn’t hit a baseball growing up and accepts help from the students to learn how, showing the children that everyone has different strengths and weaknesses.

The book ends with an upbeat lesson to never give up when things are hard. Even the font, OpenDyslexic, is designed to help young struggling readers.

Ahead of a tour to promote the new project this week, The Times interviewed Newsom about the book, his personal experience with dyslexia and parenting children with learning issues. Here’s an excerpt from that conversation, edited for length and clarity.

Why write a children’s book about dyslexia now?

Because of the experiences with my kids and the experience of being a parent created a different framework of appreciation and empathy, not only as someone with dyslexia but someone that is a parent, in my case, of kids that have learning differences — a number of them.

So, it was in that sort of relationship to that, being a parent, and then of course, having my own expression, which I wanted to communicate through the book, that led me to look for books. I was looking for picture books around dyslexia and was surprised that I couldn’t find any, but a lot of chapter books, a lot of middle-school age books that talked a little bit about dyslexia, obviously, disabilities broadly defined, intellectual disabilities. And there’s some wonderful and extraordinary book series, all kinds of incredible things. But for very young kids, particularly those that are just learning to read, I was surprised there wasn’t anything out there, and that’s what led me to do this. It was really in the absence of many alternatives, and then just a relationship as a parent growing up with dyslexia that ultimately led to the decision for the book.

How hard is it for you to watch your kids struggle with the same thing that caused so much trauma for you at that age?

I started appreciating that the trauma is maybe even more acute for the parents. So, you know, I lost my mom I think 18-plus years ago, in fact the date is on the number on the door of the school classroom, the date that she passed.

You always look back on, “woulda, coulda, shoulda,” all the things you wanted to talk to your parents about. My mom had never been able to meet my kids, but I also now deeply regret never expressing appreciation to her. Just [her] commitment not to give up on me and to, you know, struggle through that herself, which is something I just could never — you don’t think about as a kid, of course. And even when I got older, as an adult, I really didn’t appreciate it until I started to do the same with my own kids. It’s just...it’s hard. And you know, you feel like you’re a failure. You feel like there’s something wrong with you. “I’m not spending enough time with them. I’m not reading enough with them. I’m reading the wrong things. I’m letting them spend too much time on media.” All those things go through your head, and then you start to realize, wait a second, the other kids at this age are doing a little bit better, and if we’re doing the same thing, maybe there’s something else going on here.

And so, it’s, you know, all that exploration, all that emotional experience that so many parents go through, and I think the jaw-dropping thing is how many parents go through it. Millions and millions of kids struggle just like the adults struggle. It’s a lifelong issue. It doesn’t go away.

How has your personal experience with dyslexia allowed you to help your children as they try to read?

You don’t think the kids are listening to you at all. I remember reading to them and, trust me, reading to my kids is not an easy experience for me just because it’s hard to read. It’s not enjoyable. I don’t enjoy reading. I struggle through it. I’m not pronouncing the words correctly. If I’m not underlining things physically with a pen, I have a hard time spatially staying on the same line. If I’m reading casually to the kids, they prefer mom, they always say, “Where’s mom?” And I remember telling the kids, I think it was Brooklynn, I said, “Look, Daddy couldn’t read at your age, and Daddy struggled with something called dyslexia.” And she was just like, whatever. You know, she just rolled her eyes.

Two months later, I hear her talking to a friend saying, “My daddy couldn’t read. He has dyslexia.” I’m like, “What? How do you even know that?” She said, “You told me the other day.” I said, “You weren’t even paying attention.” So, any of that’s powerful for me because it makes my kids feel OK about how they’re doing right and that’s important.

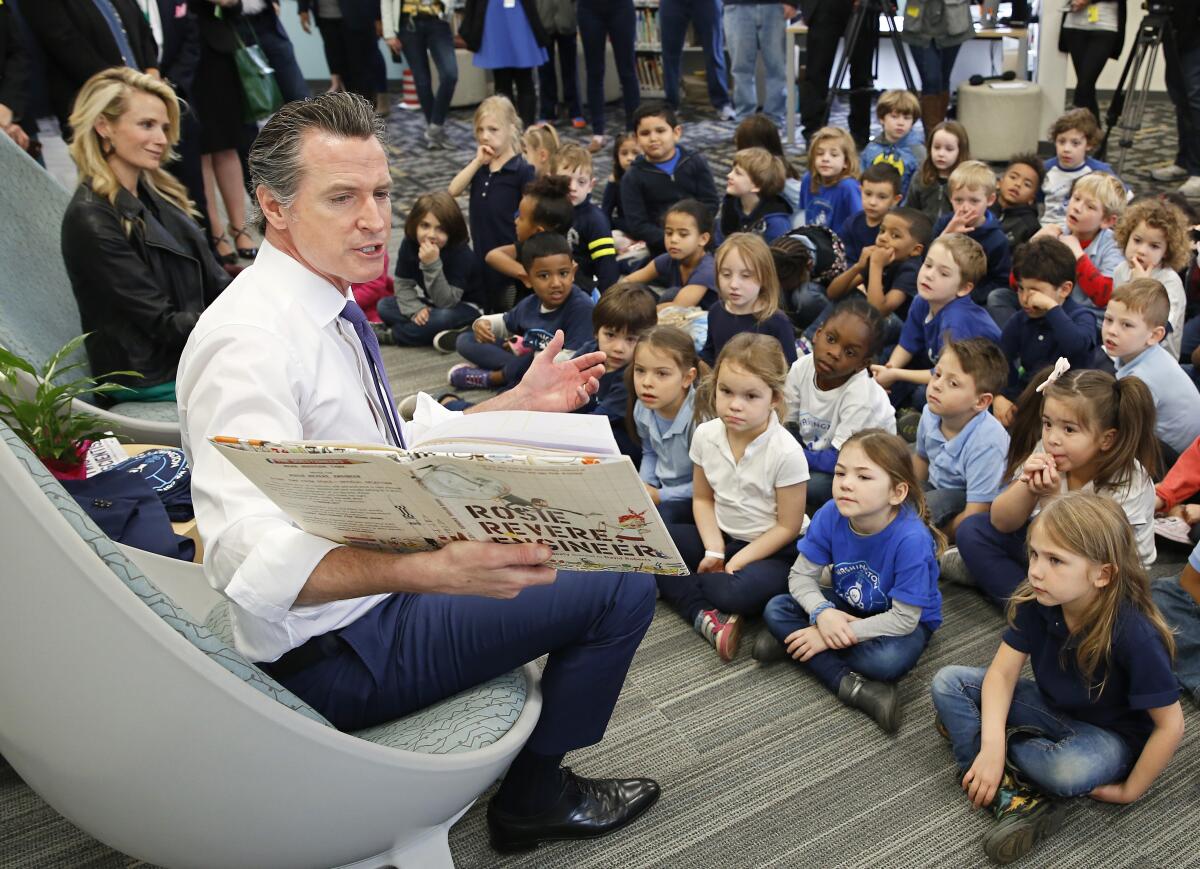

But, also, it’s an opportunity for me. You know, when I meet kids with dyslexia, or go to schools that have a focus or discipline around dyslexia, it’s empowering. It’s such an extraordinary, very intense emotional experience to be with those kids and connect with them and then invariably I’ll run across a parent. It happens all the time, where I was in a classroom talking about my experience and they come up to me, you know, sweetly say, “Thank you, because my son struggles with dyslexia and he was in the class and he didn’t say anything. And it’s just so wonderful that you said that because it made it easier for us to talk about it with him and make him feel like he’s not dumb. He’s not stupid. You know, that he’ll be OK.” And I think for the parents, it’s an expression for that as well because as parents we wonder about our kids, “Are they gonna be fast-tracked to juvenile hall and the prison system, or are they gonna be OK?” With academics, we’re so college-focused out of the womb, and everybody’s so competitive. You know, it’s hard. So when your kids are falling behind, you just go through myriad of emotions about what becomes of your children, how they can thrive, not only survive, in the world.

Gen Z has embraced “brain sports,” but as the pandemic sidelined most spellers and mathletes, Braille Challenge contenders found a way.

How much of the book did you write yourself and how much did Ruby Shamir contribute?

It was like an interview thing. We framed it, and then she put it in an outline based upon our conversations. And so, we sort of created the composites and created the characters. I talked about how important visualization is. I feel rooms and I see objects and stuff, and so she translated all that and did a draft and then we just spent two to three months just copying up versions of the draft. So, she was the rock star. She’s the writer. This was not a subject matter for her, necessarily, that she was deeply attached to, though she knew someone with dyslexia, and that’s why she said yes to doing the book. She goes, “Oh, I have a great friend who has this. This is something I’m actually interested in learning more about.” And then we went back and forth.

What else should people know about the book?

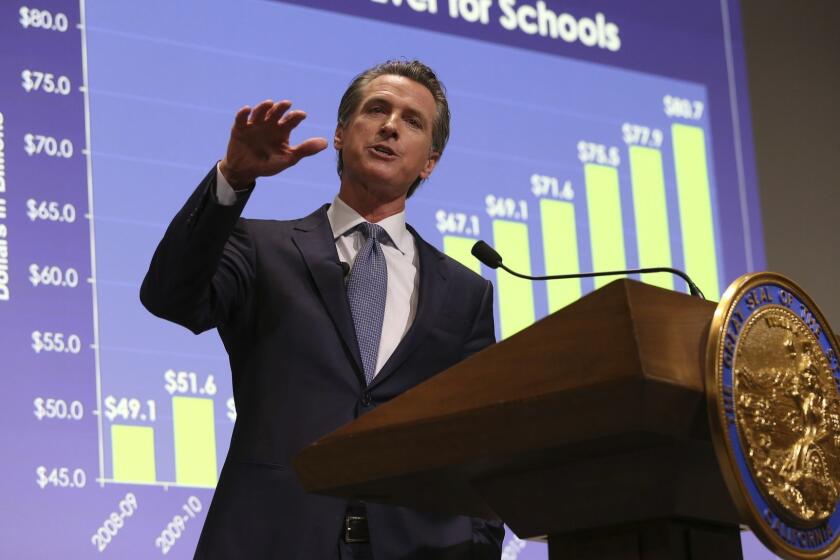

This is important, personally. I think it’s important to millions and millions of people, including arguably millions of Californians. And I just hope this opens up a door for more conversations. And also, you know, I’ve been pushing this agenda with the Legislature, but I have not pushed as far as I’ve wanted to push because I didn’t want to make it sort of — I didn’t want it to become too much about me. But what’s really interesting just in last few years as we’ve put more money in the budget — we’re doing these early screenings and UC [San Francisco] is getting funded for this early screening program — is how many members of the Legislature talk to me and with their own kids, their experiences and how many are eager to do more in this space.

I’m really excited about this space sort of opening up, literacy broadly defined, and early screening. This ties into [English as a Second Language] issues and ties in a lot of issues. So I’m really hoping in the next few years we can do some exciting and transformative things in the state, and this book, I hope, just opens that conversation up a little bit more.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.