Sex workers are pitted against each other in fight over California’s loitering law

- Share via

SAN FRANCISCO — Cold blue light from a convenience store sign spilled onto Star and Dream, not their real names, as they stood on a dark sidewalk in the Mission District, working to sell sex to johns.

In a scene repeated daily on dozens of similar “tracks” across the state, men in cars rolled slowly by the women, who are just past their teenage years but looked young enough to be on their way to a high school dance.

The drivers leaned low to peer through their windows, examining Star with half her hair in pigtails that brushed the collar of a leopard print coat and Dream in a thin black sweater pulled close over an electric-blue jumpsuit to ward off the November night.

Though prostitution is illegal in California, it is often hard to tell in open marketplaces such as this one on Capp Street, which has been running for years. When police come, it is many times more of a harassment for Star and Dream than an end to their work, they said.

“I’ve gotten tickets for just like standing right here,” Star said, referring to a loitering law that prohibits hanging out with the intent to sell sex. “I don’t go to court, so I don’t really care.”

The likely recipient of a bench warrant for missed court dates, Star and other sex workers are at the center of a heated fight in California over people criminalized for standing on street corners, and what some contend is the subjective and discriminatory criteria for loitering with the intent to commit prostitution.

That debate has fed a larger clash about how to best help those forced into prostitution without stigmatizing and harming those who choose sex work. It’s an emotional dispute that pits sex workers against other sex workers and trafficking survivors and which has larger implications for how the future of this illicit industry will be handled in California, and which now is in Gov. Gavin Newsom’s hands to decide.

In September, legislators passed Senate Bill 357, which would repeal loitering laws around prostitution, including those that target pimps and buyers. But the bill wasn’t sent to Newsom for his signature or veto. Instead, in an unusual move that insiders said was requested by the governor’s office, it was held and won’t receive his consideration until early this year.

In recent weeks, sex workers and advocates on both sides have lobbied Newsom over a decision that some contend is a first step in decriminalizing sex work in California — in effect, leaving it illegal but repealing or not enforcing laws meant to stop it.

Those in favor of decriminalization, including the American Civil Liberties Union, which sponsored the bill, say that removing legal penalties will make the job safer and provide more opportunities for those who in engage in sex work by keeping them out of the criminal justice system or allowing them to seal some criminal records.

Those opposed say it could increase exploitation and tie law enforcement’s hands when it comes to finding victims and stopping traffickers.

Though often invisible to many locals, street prostitution is a booming industry in nearly every city, one that some participants say suffered little downturn from the pandemic: Figueroa Street in South Los Angeles, Oakland’s International Boulevard, the so-called Motel Drive off a stretch of Highway 99 in Fresno, even the lots of truck stops.

Disproportionate numbers of those renting their bodies are women of color, according to studies. Some sex workers are members of LGBTQ or undocumented communities, making them vulnerable to exploitation. Though exact numbers of sex workers are hard to determine, statewide there were more than 4,000 arrests for prostitution in 2020, according to the California Department of Justice — a number that has declined by 45% since 2015 as attitudes about prostitution have changed.

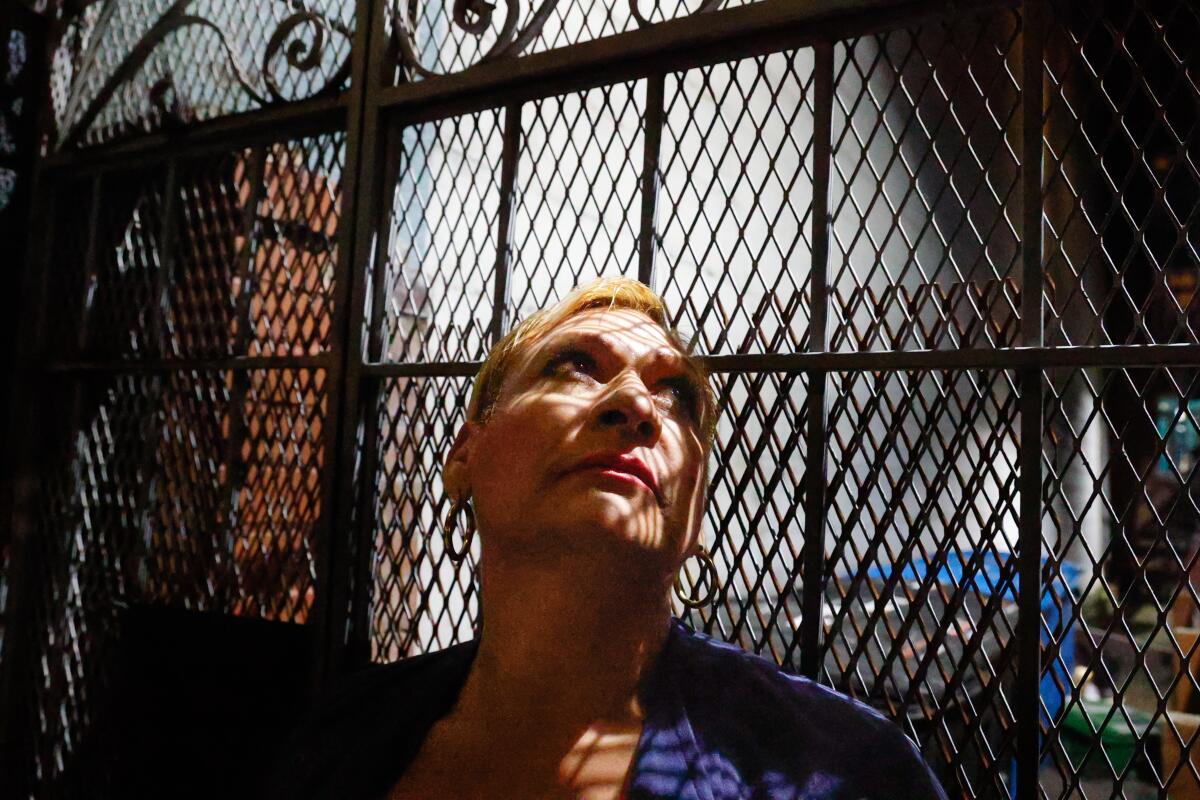

Lisseth Sánchez is a transgender sex worker in San Francisco who met with Newsom recently to plead in favor of ending loitering laws. Like many in the transgender community, she argues that loitering laws target Black, brown and transgender people and are discriminatory — outlawing “walking while trans,” she said, and giving police free rein to approach people based on how they look and where they are.

Originally from El Salvador, Sánchez said she was imprisoned and tortured in her home country for being transgender and a civil rights activist. She said police sexually assaulted her while arresting her and, in another instance, ripped off her fingernails as punishment for speaking to the media about the conditions of her incarceration.

After being released, she eventually fled to the United States to seek asylum, and arrived in San Francisco in 2011, where she supported herself through sex work. On her shirt, she wears a button that reads, “No bad whores, just bad laws.”

The location is different, but the conditions she faces as a sex worker remain harsh, she said.

“As soon as I go out on the street, the police, they shine their bright light in my face,” Sánchez said, a common complaint from sex workers who allege law enforcement uses spotlights to intimidate them. “They are always looking for a reason to mess with me.”

Being arrested unleashes a “cascade of effects,” Sánchez said. A criminal record, even for a minor offense such as loitering, makes it hard to convince landlords to rent. Credit is difficult to obtain, as are jobs and public benefits such as food stamps. Courts weigh it in custody decisions. And for undocumented people, a criminal record can make asylum and citizenship applications impossible.

Scott Wiener, the Democratic state senator from San Francisco who introduced the bill, said the penal code on loitering was “a horrible law that allows police to profile and target.”

Ending it, he said, is not about decriminalization but about protecting a group of people already at high risk for harm. He points out that New York repealed its loitering law last year.

“It makes sex workers less safe because it creates fear of the police,” he said. “If you know a cop can arrest you for how you are dressed, you are doing everything in your power to avoid the police.”

Star, the sex worker on Capp Street, said the police regularly harass her or force her to move, which makes her feel more vulnerable.

“When [police] do all the dramatic stuff they do, then we end up having to stay out here longer and do more dangerous hours and stuff like that,” she said. “It’s making it worse for sure.”

But those who support loitering laws see them as a way to reach women on the streets who are not there of their own free will, or stay because they can’t see a way out. The ability to approach street prostitutes, they argue, is a vital point of contact to offer social services. And sometimes a loitering arrest can be a way to gain time with a sex trafficking victim away from her exploiter, and the first crack in finding trafficking rings.

Eliminating loitering laws makes it “harder to investigate human trafficking cases,” said Maggy Krell, a former state prosecutor and author of the upcoming book “Taking Down Backpage: Fighting the World’s Largest Sex Trafficker,” about her prosecution of the online advertising site.

Krell said that while she doesn’t believe sex workers should be arrested or criminalized, law enforcement needs a legal reason to intervene in their lives.

“This is the quickest, easiest first step to initiate an investigation,” she said. “There are many people up and down the tracks in California who don’t want to be there, and this bill just further endangers them.”

Krell and others point out that Black and brown girls and women are disproportionally among those trafficked, for complex reasons — including generational trauma, poverty and a foster care system that inadvertently can serve as a pipeline to prostitution for vulnerable children.

“They are being the most exploited; they are the most represented out there,” said Vanessa Russell, an anti-sex-trafficking advocate in the Bay Area who founded Love Never Fails, an outreach, housing and training organization. “This is a hard thing to say, one of the things that Wiener’s bill has done that is really poor is that it’s pitted transgender people against trafficking victims.”

Russell sees an “entitled voice” in the language of the bill, which she argues is representative of a small portion of sex workers who have free agency and are engaging in the profession by choice.

“They get to pick and choose who they see and they are more established,” she said. “They have regulars and don’t want to be bothered by police.”

Russell said many young women in Oakland and other places where she works don’t have that freedom.

“They are standing out in the middle of the street in the middle of the night. They’re cold and hungry and their pimp is across the street in an apartment watching them,” she said.

While San Francisco, Los Angeles and some other cities have robust community-based organizations that help sex workers off the streets, the majority of the state lacks groups with the funding and reach of their larger counterparts. Law enforcement is the de facto exit strategy — a faulty intervention that few see as adequate.

Even for women who accept the help of police after an arrest, there often aren’t enough resources — housing, child care, mental health care, job assistance — to successfully build a different life.

Oftentimes, what is available is tied to cooperating with law enforcement, rather than focused on supporting victims to move past their exploitation. Those supporting ending loitering and those against it agree on this: If police are the best way out of prostitution, California is failing some of its most vulnerable women.

But Senate Bill 357, critics argue, removes that flawed offramp without replacing it.

“I don’t want to fight against LGBTQ people. I love them and want them to be supported,” Russell said. “The issue here is there are no exit strategies built in this bill for any of them.”

One major sticking point for advocates including Russell are provisions in the bill that eliminate loitering laws for potential johns and traffickers. Critics said nixing those statutes is a move toward full decriminalization — laying the groundwork to end enforcement beyond loitering by sex workers.

Krell, the former prosecutor, said, “You can’t talk about this bill without talking about decriminalization.”

“You are basically telling cops, ‘Hey, keep driving,’” Krell said. “The Legislature should go back to the drawing board and really look at this statute and figure out how to split up people who are predators and people who aren’t.”

Minouche Kandel, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU of Southern California, said while her organization has long supported decriminalization and the bill is “starting the conversation,” it should be judged on its own merits.

“We like to see ourselves as a leader in civil rights and we are behind in this law,” Kandel said.

Jess Torres, an anti-trafficking advocate in Los Angeles, said decriminalization would end penalties for what Torres sees as a way to survive in hard circumstances.

Last year, Manhattan’s district attorney announced he would no longer criminally charge those selling sex, but would continue to go after buyers and traffickers, prompting similar moves from other New York prosecutors.

In late 2020, Los Angeles Dist. Atty. George Gascon issued a directive that stopped nearly all prostitution-related loitering prosecutions.

Torres and other supporters of decriminalization said they would like to see more approaches that put helping sex workers above “chasing down the bad guy,” and a switch to a greater focus on restorative justice, the idea of helping perpetrators make amends without criminalization, not just for those selling sex, but also for buyers and perhaps even some traffickers.

Torres said current laws against buying sex from consenting adults carry minimal punishments and have done little to stop prostitution, and laws against human trafficking address the exploitation of minors and others without criminalizing victims.

Laws such as loitering, Torres said, add more harm than good in a system already too focused on punishment, and removing them is a start to acknowledging that “sex work is work” and what is needed are “spaces that facilitate health and healing.”

Torres says that while ending loitering laws does little to fix the yawning gaps in the system for those who want out, it’s “a first step” in rethinking the problem.

But the idea of curtailing even a weak tool to hold johns and pimps accountable is infuriating to critics. Decriminalization, they contend, will only increase exploitation by removing consequences. Already, researcher Melissa Farley said, 16% to 35% of men in the United States have paid for a sexual act.

“I am never going to be a proponent of an industry that has historically been racist and sexist and violent toward women,” said Russell, the Oakland advocate. “I don’t see any positive outcome for us going down this path of decriminalization.”

For Sánchez, the San Francisco transgender sex worker, the debate is one of human rights for people like herself.

“Sex work is not the same as sex trafficking,” Sánchez said. “It is absolutely not necessary to arrest people for their own good.”

On the same night Star and Dream stood on their corner, Sánchez helped host a Thanksgiving dinner for other Latinx trans sex workers in the backroom of a Tenderloin health clinic. More than a dozen people ate roast turkey and tortillas from a buffet table that sat near bowls of gold-wrapped condoms and lube, free for the taking.

It was a rare respite for a group of people who are often discriminated against to the point of violence. In 2021, more than 50 transgender people, many sex workers, were killed nationwide — the deadliest year on record.

But Sánchez wanted to talk only about Senate Bill 357, and what the isolation of prostitution feels like.

“It’s just like a recording in the head,” she said. “That nobody is going to help you, nobody is going to help you, nobody is going to help you, because you are a sex worker.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.