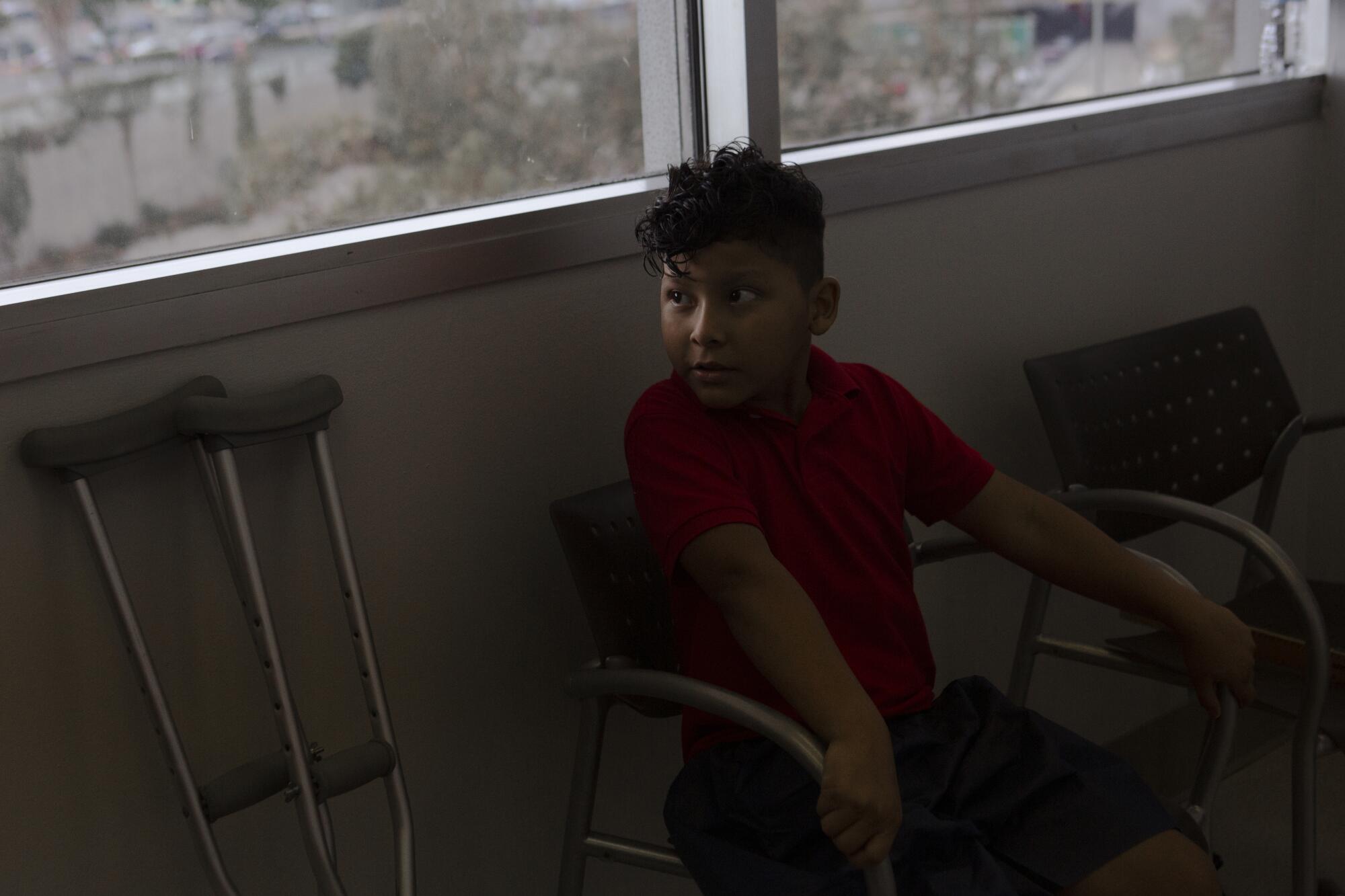

Their condition could be described, generously, as ramshackle — a plastic kiddie car and a battered pair of crutches.

Until last year, both were essential props for Efraín Ordóñez Hernández, a boy from Mexico who in his 10 years has known both extraordinary trials and extraordinary blessings.

Born with a rare congenital condition that twisted his right leg and rendered it nearly 11 inches shorter than his left, Efraín relied on the car and crutches to get around, to keep up with friends, to not fall further behind in life. Although his world has spun in a dramatically different direction since December, the toy car remains in his grandparents’ house, and the crutches are stowed under his bed — totems, so Efraín won’t forget his past.

“I’m not going to throw them away,” he tells a visitor to his family’s rented East L.A. home.

In Mexico, Efraín relied on his grandfather Carlos to constantly replace his crutches’ crumbling rubber tips. Years later, after his parents braved a desert crossing to eventually bring their family to Los Angeles, he acquired a new set of crutches — Efraín’s first blessing.

But, the boy insists, “I love the others more.”

Sitting with his mother on the front porch of their house, Efraín — on most days, a vivacious and funny child — was transported in his mind to a painful past of ridicule and casually cruel schoolyard taunts.

“Some children called me ‘Pata Cuta’ — ‘Crooked Leg,’” he said. His mother, hearing of this for the first time, flinched.

During Efraín’s early years, while his parents futilely sought financial help and medical expertise, his grandfather removed the right pedal from a bicycle so that Efraín could pedal it using only his left leg. He could scoot around in his toy car in the same way; three times, its worn-out tires had to be replaced.

The car proved as resilient as its owner — a second blessing.

When he was 3, Efraín learned to walk with crutches. At 4, he started riding all-terrain vehicles. By 5, he could ride a bicycle. These days, his preferred mode of transport is a blue 2022 Yamaha TTR 90 motorcycle. He only needs someone to steady it when he gets on; he rides solo.

But additional blessings were needed for Efraín to be made whole.

Blessing No. 3 was his parents’ decision to risk everything by immigrating to the United States in 2018. The fourth was a surgical procedure called rotationplasty, performed by a team of UCLA specialists.

In the midst of their difficulties, his family joined in what they call “chains of prayer.” The boy’s mother, her mother-in-law and the parishioners of the evangelical churches where they congregated prayed every time his parents took him to a doctor’s office.

“Faith has been the support of everything,” said Nancy Ordóñez, whose years-long struggle to obtain medical care for Efraín led to her being baptized in the Apostolic Church of the Faith in Christ Jesus last summer.

“God did everything. He heard my prayers,” she said. “When someone asks me, I tell them: ‘God’s timing is perfect.’”

Latinos are the fastest-growing group of evangelicals in the United States. They’re increasingly driving a political realignment.

Yet one more blessing, the fifth, came in the form of a steadfast older friend who’d lived through the same struggles and helped guide Efraín on his journey.

::

Efraín was born in April 2011 in the heavily Indigenous state of Chiapas, on Mexico’s border with Guatemala. His mother, now 31, took care of the home. His father, Efraín Ordóñez Solares, also 31, worked as a motorcycle mechanic. The couple also have two daughters, Britany, 15, and Briyith, 4.

Scuffles have broken out in the Mexican city of Tapachula between authorities and some of the tens of thousands of migrants who have been stranded there.

The delivery was normal. Hospital staff were getting everything ready for Ordóñez to go home with her baby when her husband arrived.

“Look at his foot,” he said to his wife, with a startled expression. Doctors and nurses were promptly summoned.

“The doctors hadn’t told us anything,” his father recalled. “I don’t know if they didn’t realize it.”

Upon leaving the hospital, Ordóñez went into shock. “I sincerely said, ‘Why me?’”

The diagnosis was congenital femoral deficiency, which causes certain parts of the leg to be underdeveloped and sometimes crooked. Dr. Anthony Scaduto, president of the Orthopedic Institute for Children, says this condition occurs once in every 50,000 births, and often results only in a mild deficiency that can be resolved with leg-length-matching surgery.

Severe cases require major reconstruction or even amputation. But there is another remedy, a procedure known as rotationplasty, which allows the patient to use a walking prosthesis. Cases like Efraín’s are rare.

“If you look at how many patients are born with severe form of this condition,” said Scaduto, chief of pediatric orthopedic surgery at UCLA Health, “it’s probably closer to one in a million.”

In some ways, the one-in-a-million boy’s childhood was blissfully ordinary.

At his grandparents’ home he climbed trees and clambered over the roof. He helped his grandfather tend the surrounding banana plantations. At school, he didn’t hide from physical education class, though he struggled to keep up with classmates.

“Yes, I could run,” he recalled, “but they beat me.”

Meanwhile, his parents’ searches for medical help usually went nowhere.

“That leg is not going to work for him,” said a doctor when Efraín was 1 month old, words that felt to his mother like a slap in the face. She never went back to that doctor.

His parents then appealed to Teletón, a foundation that serves children with disabilities. “His problem is very severe. You can’t do surgery,” an orthopedist from the foundation told the family.

But the foundation did offer therapy. For almost five years, Ordóñez took Efraín a few times each month to Teletón’s headquarters for therapy, cradling him in her arms on public transportation in a wearisome 12-hour round trip.

Running out of options, money and time, the parents immigrated to Los Angeles, temporarily leaving their children behind with grandparents. In Chiapas, Ordóñez Solares earned only 4,800 pesos (about $237) per month fixing motorcycles. In California, he devoted himself to construction, and Ordóñez started cleaning houses.

‘Efraín is a story that inspires. It is a reflection that we are all capable.’

— Marissa Martínez, Brooklyn Avenue School principal

One day in August 2020, en route to work, Ordóñez passed the Orthopedic Institute for Children on West Adams Boulevard, near USC.

“Isn’t that a hospital for children with bone problems?” Ordóñez asked her traveling companion. “How I would like my son to be cared for there!”

Yet like many immigrants without legal status, Efraín’s parents were hesitant to approach hospitals. Dr. Edgar Chávez, medical director of the Universal Community Health Center in Los Angeles, said that many new arrivals fear the onerous cost of U.S. healthcare. Others fear they may stray into the sightlines of immigration agents — even though, Chávez said, that risk is minimal.

In January 2021, Ordóñez took Efraín to a community clinic for a minor allergy, and a doctor there promised to refer the boy to an orthopedist. Three days later, she was contacted by OIC, the medical center that she had seen five months earlier.

::

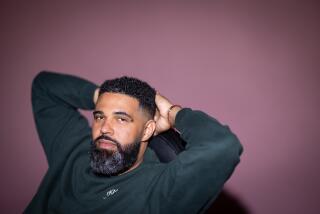

At this point, Blessing No. 5 arrived for Efraín and his family — in some ways, the most unlikely of all.

In the Coachella Valley, 130 miles east of Los Angeles, lived José Luis Hernández, 22, who’d been born with a right leg about 2 inches shorter than his left.

He was 6 when his mother, Ana Hernández, emigrated from El Salvador to California with the idea of helping her son. For years she worked 18-hour days washing dishes in a restaurant to pay for her son’s treatments, including 10 surgeries, in El Salvador. She and José Luis finally reunited in California in 2014.

Since 2018, Hernández has worked in a department store. He started out unpacking clothes, but last June he was elevated to manager, an opportunity that opened up after he was able to obtain a prosthesis with help from OIC and UCLA, whose surgeons performed rotationplasty a year before.

“In my past I always needed someone’s help, and I didn’t like that others made me feel less, that people had to do things for me,” Hernández said. “Now I feel much better, because I don’t need help from anyone, I can do many things alone.”

Including helping others.

As Hernández was finishing his treatment and advancing in his independent life, Efraín started his checkups at OIC. One day last March, Efraín and Hernández showed up at OIC at the same hour. For both, it was like looking into a mirror.

“I felt that I saw my reflection next to me,” said Hernández, who hadn’t met anyone with his condition.

“I saw him normal, walking,” recalled Efraín. Neither knew that medical center staff had arranged the seemingly chance encounter, to inspire the boy with Hernández’s example.

Efrain entered UCLA Santa Monica Medical Center on June 10 for his own 10-hour operation. It was performed by Scaduto and Dr. Nicholas Bernthal, orthopedic surgeon and director of the UCLA Health Orthopedic Center.

Efrain’s right leg was so short, his right foot was level with his left knee. To create a better attachment for a prosthesis, the right leg was rotated 180 degrees so that his heel faced forward, while his toes pointed backward.

“His ankle becomes a knee,” Bernthal explained, “and it will allow him to have two functional legs and get out and kind of go walking without any crutches or assistive devices.”

Rotationplasty surgery was introduced in the 1930s to treat congenital deficiencies in the femur. According to Bernthal, the treatment has been perfected in the United States in recent decades.

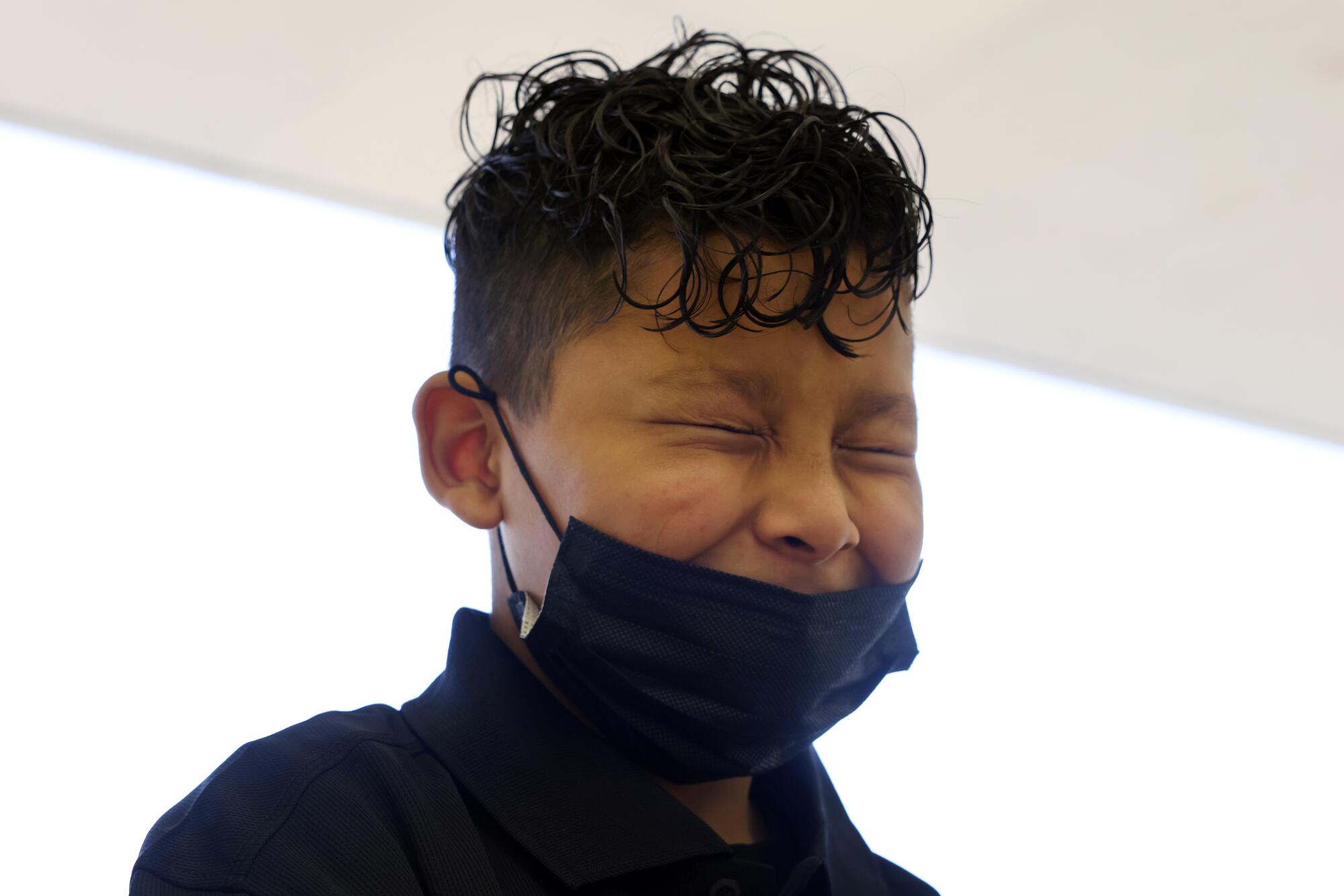

Efraín’s surgery had gone well. But its true impact wouldn’t be known until the boy tried on his new prosthesis.

::

On Dec. 8, the clock struck 7:46 a.m. as Efraín woke up. It had been nearly six months since his surgery, and he’d marked this date on his calendar.

“It’s today, it’s today!” he shouted.

It had been a long wait, and a slow, at times painful recovery from his operation. Three months after his surgery, he’d gone to Active Life, a clinic, to have his foot measured for the prosthesis.

“It’s tight,” he said, trying on the transparent mold.

“Try — you haven’t tried,” Ordóñez Solares told his son.

A specialist adjusted the mold and the boy’s foot slid in easily. While Efraín underwent a series of postsurgical therapies, the finished prosthesis was constructed out of carbon fiber. In November, he tried it out for the first time. Over the next four weeks, he practiced various exercises at home to help regain his balance.

On the morning of his big day, he was desperate to get to his appointment at OIC, where a lively children’s Christmas party was underway. Escorted by his mother and medical staffers, he went into Room 4 and sat on the edge of a bed while waiting for Bernthal and Scaduto.

When they walked in, Scaduto held the prosthesis in his hands. “Ready?” he said. When Efraín took his first steps without leaning on his crutch, a crowd of about 20 people who’d gathered in the corridor broke into applause.

“You can take it,” Scaduto told Efraín, indicating the new prosthesis. “Now, to celebrate Christmas!”

The Hollywood ending to Efraín’s story didn’t come cheaply.

OIC estimates the cost of his treatment at somewhere between $100,000 and $125,000 in the first year. But his family will not have to pay a penny. Karla Delgado, assistant director of community outreach at OIC, said that donors cover the expenses of families like Efraín’s with low incomes and little or no medical insurance.

“If it weren’t for them doing their bit, there are thousands of children who would not have the fortune like Efraín to come here,” Delgado said. OIC also operates a program for international children, extending assistance to patients who are outside the United States.

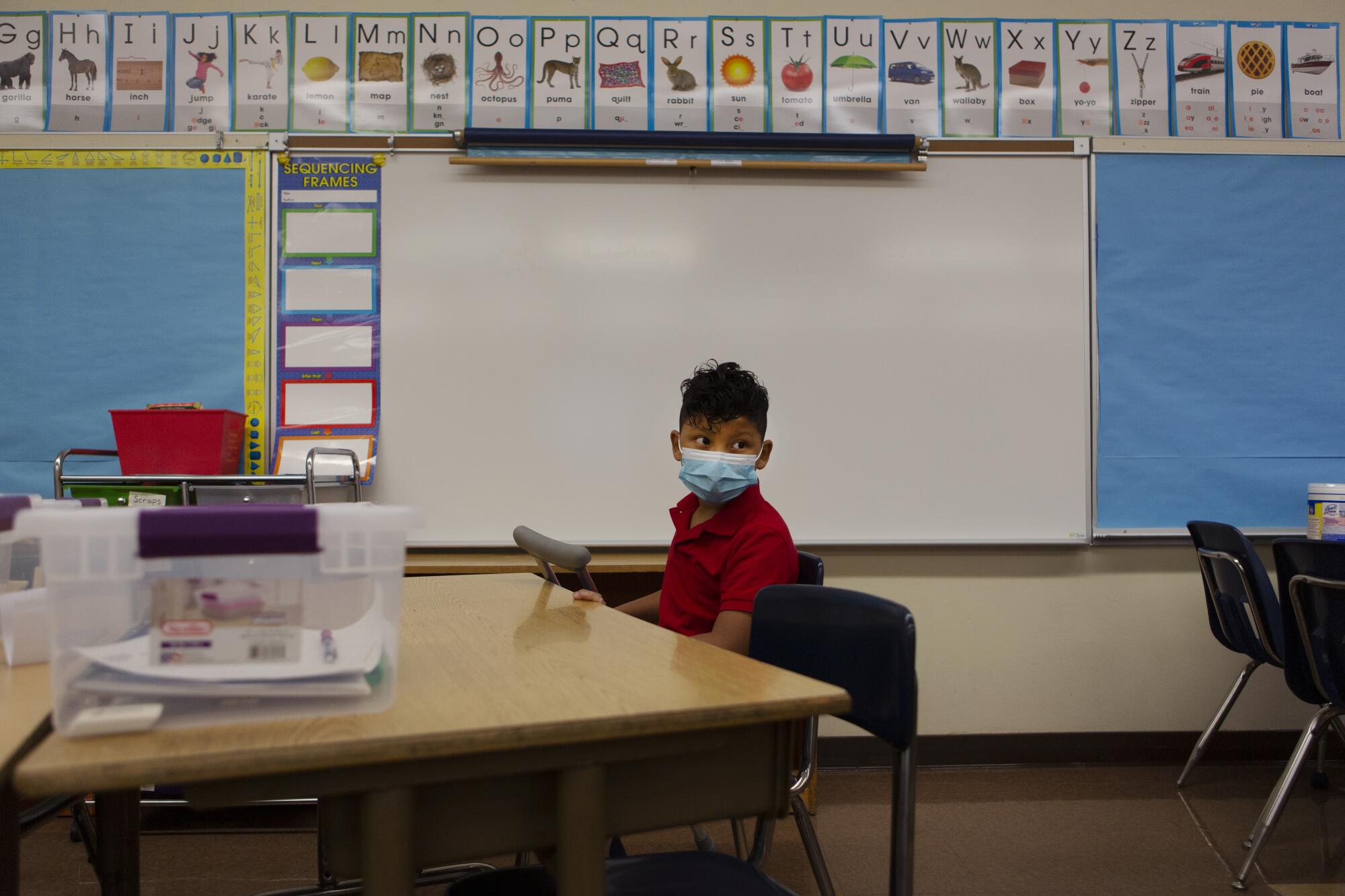

Now a fifth-grader, Efraín can play soccer, ride a scooter and isn’t afraid to hit the dance floor with his friends at parties. His teachers say he still is somewhat shy about speaking English, and he struggles a bit with math. But he’s making progress, his mother said, and feels accepted and supported by his classmates.

Bitter rivals U.S. and Mexico soccer face off at Estadio Azteca on Thursday, with a World Cup berth and Tata Martino’s job on the line.

“Efraín is a story that inspires,” said Marissa Martínez, principal of his school, Brooklyn Avenue School. “It is a reflection that we are all capable.”

The first day he went to school with his prosthesis, Dec. 13, Efraín felt nervous. But he was philosophical about it. “I thought I was going to fall, and I did. We were running and I fell. It is part of the process.”

These days, Efraín’s walking is improving, though he sometimes needs the crutch for balance. His mother, along with relatives and the pastor at the family’s church, maintain the “prayer chains.”

And Efraín has stayed in touch with his older guide and friend Hernández, through calls and texts, since the surgery. “José Luis was a great inspiration,” Ordóñez said a few days ago.

As soon as he lightens his workload a bit, Hernández said, he plans to invite Efraín out — for a walk.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.