It’s called the zipper merge, and traffic-jammed California drivers do it all wrong

- Share via

It’s a familiar scene: You’re driving on a California freeway at rush hour. As you crawl through traffic, you notice your lane is ending.

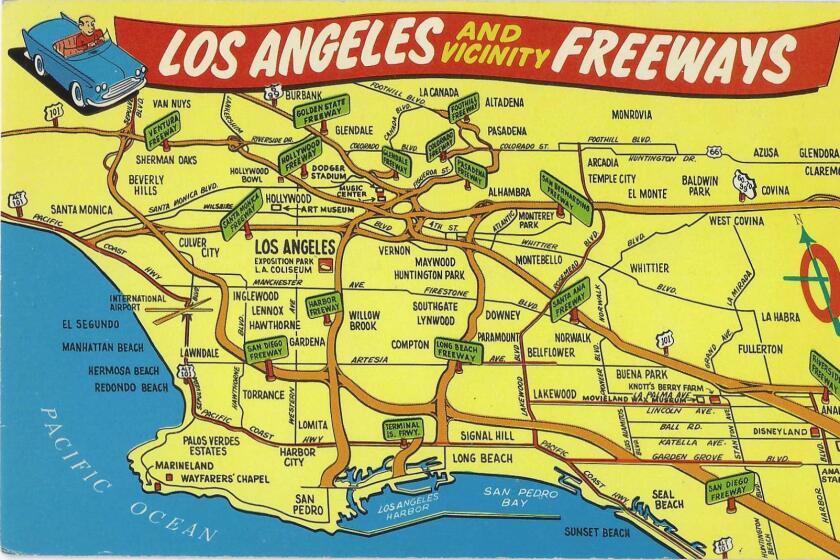

It could be road construction forcing the lane closure, or maybe it’s just one of L.A.’s jarring freeway entrances or interchanges.

And you’re always left with a choice: Do you merge early, or do you wait until the last minute?

Merging early seems to be expected and commonplace, considerate even. You worry that waiting to merge may be seen as rude, or cutting in line. And in a time when reports of road rage incidents have surged amid the pandemic, such a move may mean conflict.

But despite our projections onto other drivers, a growing body of research over the past decade has pointed to the benefits of merging late, with experts finding that it is actually the more efficient and safer thing to do, especially in heavy traffic.

The driving method even has a name: the zipper merge.

Parking in Los Angeles is about luck and skill. So save time and money by learning these hacks with yellow curbs, green curbs, holiday rules, valet and more.

The name is literal, evoking a zipper made of cars using both lanes to their fullest extent. When one lane ends, cars take turns merging, seamlessly zipping between one another.

After Minnesota became one of the first states to tout the method in about 2011, a wave of states — at least 33 others — have since adopted or promoted zipper merging to their drivers, mostly for construction zones.

And states have been creative with their education: Kansas traffic officials spread the word through talking construction cones. Oregon officials made a jingle. And in Montana, traffic officials moralized the issue, discussing the definition of niceness.

In 2020, Illinois became the first state to have zipper merging written into its traffic laws, which fine offenders who fail to merge late. A similar law is expected in Utah, as well as North Carolina, where House Democrats celebrated its passage with zipper merge-themed merch.

Yet even in states where zipper merging is encouraged, it has still been a challenge getting drivers to share space on the road.

“It’s a bit of a collective idea that we’ve got to get everybody to understand, that it’s OK to use the lane until it closes, and it’s OK to let a car in front of you,” said Jacob Loesch, spokesman for Minnesota’s Department of Transportation. “Driving is such an individual thing, right? You can control what’s happening in your car. You don’t know what other drivers are doing, and so you know, it’s a challenge.”

California is among the minority of states that have not adopted the method. In fact, according to a Department of Motor Vehicles spokesperson, it trains its drivers to do the opposite around road work zones: merge early.

Officer Shanelle Gonzalez, a spokesperson for the California Highway Patrol, said the zipper merge isn’t something officers are trained on. She instead gave general advice: that drivers simply merge safely, and to defer to the basics of using mirrors and turn signals properly.

There is no Beverly Hills Freeway. Nor does the 2 connect to the 101. What even is the 90? These are the freeways that didn’t happen as planned.

When Alena Maschke, a freelance reporter, moved to the U.S. from Germany, where the zipper merge had long been written into traffic laws, she quickly learned the method of merging late was hardly a global import like the BMWs, Mercedes-Benzes and Volkswagens joining her on American roads.

“People will just not let you in,” Maschke said.

She first started her driver’s training in New York, got her license in Florida, where in Miami she’d traverse eight-lane freeways, and finally moved to Los Angeles in 2017, spending hours commuting from Koreatown to Long Beach. After close calls with drivers who’d rather collide with her car than let her into the lane late, Maschke adapted.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

“And my mom [during visits from Germany] would always comment on my aggressive driving style,” Maschke said. “And I would tell her, ‘Yeah Mom, that’s because if you don’t get in here, no one’s going to let you — it doesn’t work the way it works at home.’”

In his 2008 bestselling book, “Traffic,” Tom Vanderbilt leads off the read with discussing the zipper merge, zooming in on its naysayers and supporters.

He said he began to see zipper merging as less of a traffic problem, and more of a behavioral one, adding that “everyone seems to have a moral and intellectual stake in it, as it taps into strong normative feelings of fairness and justice.”

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Vanderbilt referred to the road in his book as, “a place where many millions of us ... are thrown together daily in a kind of massive petri dish in which all kinds of uncharted, little understood dynamics are at work,” a mingling of differences — “ages, races, classes, religions, genders, political preferences, lifestyle choices, levels of psychological stability.”

Since the release of his book, the zipper merge has grown in popularity.

Even so, especially amid the pandemic concern of road rage, zipper merging remains a point of contention.

“Because [zipper merging is] viewed ambiguously by people, there’s always a chance for someone to feel that some other driver is doing the wrong thing — and it’s often seen as somehow directed personally toward the offended driver, when in reality the person committing the behavior probably had no clue,” Vanderbilt said. “The pandemic seemed to unleash some of our worst impulses, as if people, feeling their ‘freedom’ constrained in other areas of life, decided they no longer needed to conform to petty regulations on the road.”

If you’ve been thinking about going car-free in L.A. or even just driving less, these riders’ stories can help you get started.

Understanding the challenge, supporters of the zipper merge such as Loesch remain hopeful drivers can get behind the method.

For William Van Tassel, the head of driver training at the American Automobile Assn., the easiest sell for those skeptical of the zipper merge is that it will get drivers to their destination faster.

“Everybody wins is really the benefit,” Van Tassel said.

Christopher Vaughn, a researcher at North Carolina State University who helped write a 2018 study on the zipper merge and is conducting a separate one for the Federal Highway Administration said he has anecdotally seen more acceptance of merging late.

He said signage encouraging the zipper merge and press releases from public agencies, pointing out where and how zipper merges ought to be used, are also essential for its success.

On a recent phone call home to Germany, Maschke said her mom shared how German roads are hardly a utopia when it comes to merging. In the early days of the zipper method, Maschke’s mom said, German drivers were also skeptical of the new merging laws.

“In the beginning when it became a thing, when they put up the first signs, saying, ‘Here you should zipper merge,’ people weren’t getting it either, or weren’t accepting of it,” Maschke’s mom told her. “It took a little bit of time.”

The city may be the nation’s capital of car culture, but pressure is building to get more people out of their emission-spewing rides.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.