‘Bad City’ alleges bad behavior — by a medical school dean, USC and within The Times

- Share via

It would be hard to find a worse couple of years than 2016 and 2017 for two major Los Angeles institutions: the University of Southern California and The Times.

That’s when a young drug addict overdosed on crystal meth and GHB in a Pasadena hotel room while partying with Dr. Carmen Puliafito, dean of USC’s Keck School of Medicine. It also was when two high-level editors then at The Times were accused of trying to stop the paper’s own reporting team from covering the USC scandal.

The Times eventually published a lengthy piece on USC’s major ethical lapses. But to do so, a clandestine team of reporters had to hide their early efforts to cover the university from the paper’s top management, according to “Bad City: Peril and Power in the City of Angels,” out this month.

“A Times Investigation: The Secret Life of a USC Dean” did not run in the paper until more than a year after Sarah Warren survived that overdose. The piece kicked off a series of hard-hitting stories on Puliafito and led to a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation into Dr. George Tyndall, the USC gynecologist accused of sexually abusing hundreds of students.

For nearly 30 years, the University of Southern California’s student health clinic had one full-time gynecologist: Dr.

Although USC’s flaws have been exposed, The Times’ largely have not. Until now. In “Bad City,” Times investigative reporter Paul Pringle — who led the paper’s efforts to scrutinize Puliafito and USC — dissects how the university and several of The Times’ top editors, now no longer at the paper, allegedly fell from grace together.

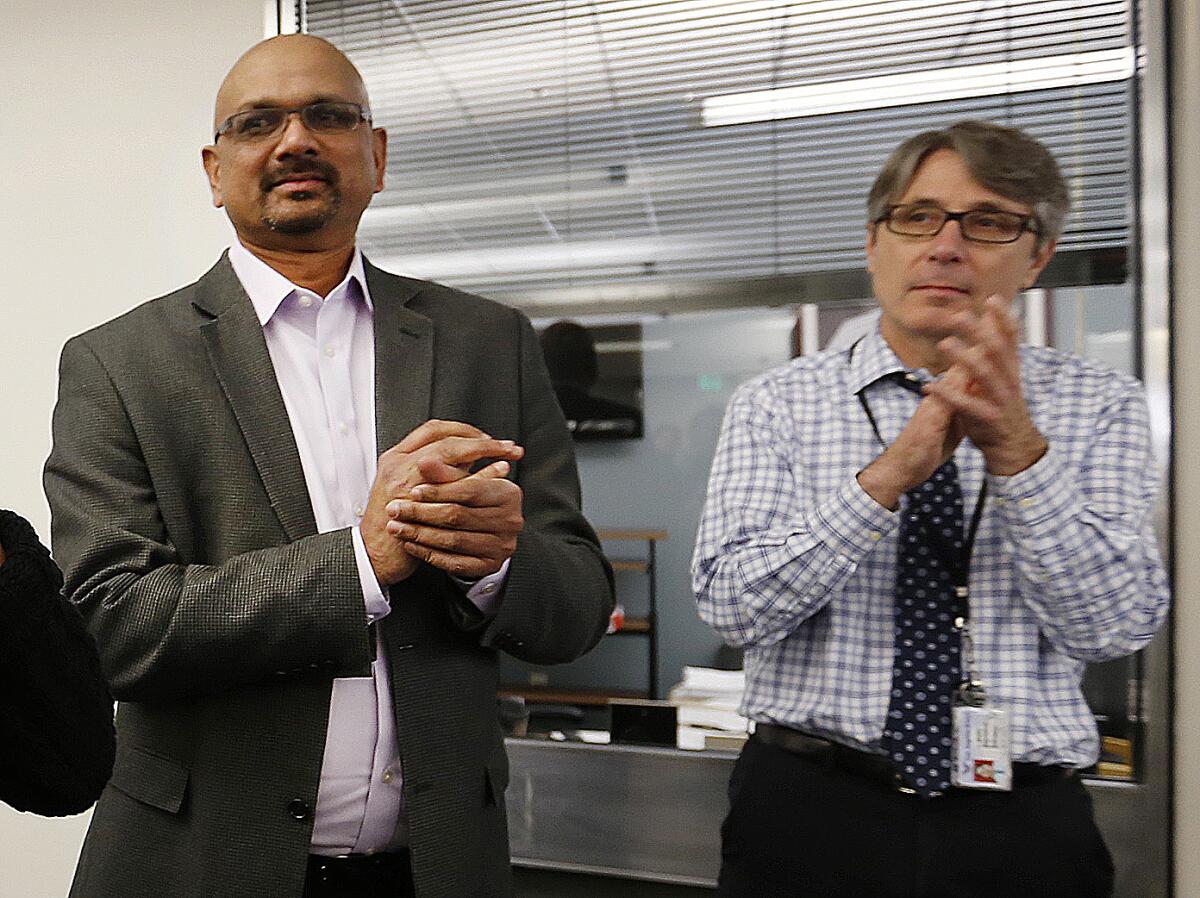

Managing Editor Marc Duvoisin and publisher and Editor-in-Chief Davan Maharaj were fired in 2017. Tronc, which owned The Times then, stated publicly that they were terminated as part of a management restructuring and there was no conflict of interest between the two men and USC.

But under their leadership, Pringle wrote, “a balance of power that existed between USC and the Times for generations had been subverted – so that it had become tilted in USC’s favor.”

“Bad City” contends that the actions Duvoisin and Maharaj took to stymie the USC investigation went against the most basic tenets of journalism and tarnished the news organization’s credibility at a time of rampant distrust of the media.

“The largest, most important media company west of the Potomac and one of Los Angeles’ oldest institutions had an opportunity to do the right thing and lost its way,” Pringle said in an interview. “As cynical as I’ve been for a long time, it stunned me. I just couldn’t believe what I was going through every day.”

Duvoisin is now editor-in-chief of the San Antonio Express-News. Maharaj remains in Southern California, where he said he is involved in several journalism and literary projects. Neither man has read “Bad City.” When told of allegations made in the book, they vociferously denied them.

“This whole storyline — about a corrupt newsroom management at The Times that protected USC and that tried to suppress the Puliafito story — in its broad outlines and in its details is untrue, period,” Duvoisin said. “It is a myth, it is an invention, and it is, frankly, pathetic … that five years after the story was published with all this going on in the world, we’re still talking about this.”

Maharaj called assertions that decisions about The Times’ coverage of USC ever tilted in the university’s favor “ridiculous.” “I and the other honorable senior editors who worked with me would never let any person or entity, including USC, dictate any aspect of our coverage,” he said.

“Bad City” is part exposé, part primer on investigative journalism, part saga about the abuse of power. At its heart, it is the story of a whistleblower and a newsroom trying to do the right thing against great odds.

It also reflects the challenges of the modern media landscape and the intense discussions surrounding the media’s traditional role of holding the powerful accountable.

Society’s trust in once-revered institutions has tumbled, and pressure has grown for media companies to provide greater transparency about how they do their work and their relationships with those they cover.

The story begins in Pasadena, on March 4, 2016, when Devon Khan, reservations supervisor at Hotel Constance, was summoned by a housekeeper to a room on the third floor. A rumpled Puliafito answered the door. The floor was scattered with drug paraphernalia. A woman dressed in a robe and pink panties was unconscious.

In USC’s lecture halls, labs and executive offices, Dr. Carmen A. Puliafito was a towering figure.

Puliafito didn’t call 911. Khan did. Paramedics arrived. So did the police. No arrests were made; no police report was filed.

Khan was outraged. Eventually he emailed the Pasadena city attorney. Nothing happened, according to “Bad City.” He called the office of C.L. Max Nikias, then president of USC, and gave two women there a full report. Nothing happened. He called The Times but was too terrified to leave a message.

So he decided to drop the matter. Then he met Times photographer Ricardo DeAratanha at a neighbor’s house. Khan filled him in about the overdose and the unconscious woman and the famous man and the official inaction.

“DeAratanha listened closely,” Pringle wrote, “and I got Khan’s tip two days later.”

Pringle was assigned to check it out because of his earlier exposé about USC’s football program and the fact that he and a colleague were investigating the university’s athletic director at the time.

Six months after the overdose, five months after he began reporting on Puliafito, Pringle felt he was ready to start writing. He also was scheduled to have knee-replacement surgery. As he left the newsroom for the last time before the operation, he stopped by Jack Leonard’s desk.

At the time, Leonard was the paper’s law enforcement editor. He also was a good friend. Pringle told him about “the dean, the young woman, the overdose, … USC’s silence, the 911 recordings.”

Leonard agreed that the story was amazing and then asked a question that “Bad City” asserts would define the next several months of Pringle’s life. According to the book, he nodded toward Maharaj’s and Duvoisin’s offices and asked, “What makes you think they’ll run it?”

Getting the story into print, “Bad City” argues, was at least as arduous as the investigation itself. First, Duvoisin wanted to take off the label “Times Investigation,” because, according to the book, the term implied wrongdoing on the part of USC.

In a recent interview, Duvoisin said he does not remember wanting to strip the first version of the story Pringle handed in of the “investigation” label.

“It’s possible,” he said, “that I thought that the information we had was not robust enough to support something as assertive as that. That it might be wiser just to let the information speak for itself and not characterize it as an investigation.”

Then, the book maintains, he tried to stop Pringle from approaching the USC president at his home. Puliafito had resigned his position as medical school dean, although he remained at the university. Pringle wanted to confirm that Puliafito had been demoted because of the overdose and subsequent Times reporting.

“Never in my career had an editor tried to stop me from knocking on the door of the subject of a story,” Pringle wrote. “Nor had an editor ever required that I get clearance to do so. Editors are supposed to make certain that reporters knock on those doors if all other attempts to reach the subject failed.”

Duvoisin said he thought Pringle’s efforts to contact Nikias were “a bit over the top” and “verging on harassment.” But, he said, “I did not try to prevent him.”

Pringle countered that characterization: “It could not be more routine to knock on the door of the subject of a story when that person does not respond to phone calls, emails and other attempts to engage him.”

He said he would expect to be disciplined by an editor “if I failed to do that on a story of such importance.”

When Pringle went to Nikias’ house, the university president wasn’t there. He gave a note on Times letterhead to Nikias’ wife. It was returned, unopened, to Maharaj the next day with a complaint from Brenda Maceo, USC’s vice president for public relations and marketing, according to “Bad City.”

“Pringle has again crossed the line,” Maceo wrote. “We understand he is doing his job, but we also expect a degree of respect and professionalism between our organizations.”

Four editors worked on the story. The Times’ newsroom lawyer had reviewed it. It was scheduled for publication. But several days before it was supposed to run, according to the book, Duvoisin emailed Pringle that Maharaj, the paper’s top editor, needed “to think on it overnight and will meet with us in the morning.”

At the meeting, according to “Bad City,” Maharaj said, “We are not going to publish this story.”

His reasoning, Pringle wrote, was that the paper could not prove “conclusively that Nikias removed Puliafito because of the overdose. That was like saying we couldn’t publish a story on the occurrence of a crime without first solving it.”

And that, he wrote, made him realize what was happening: “Nikias was essentially in charge of the story. …. If he talked, the story might run. If he didn’t, it wouldn’t. It was a cover-up artist’s dream.”

The story was killed, according to the book.

Pringle was furious. “I wasn’t trying to publish something about a defense contractor skimming,” he said in an interview. “This was about real people, human beings. Here was a practicing eye surgeon who was using meth and heroin and providing those drugs to desperate young people. None of that mattered. Nothing.”

Maharaj denied the allegations and said “the story was sent back for more reporting.”

“I specifically said at the meeting that I was not killing the story and that Pringle needed to do more reporting and not rely so much on a heavily redacted police report,” he said. “I thought the story was too thin and we needed to know more.”

The next day, according to the book, Matt Lait, Pringle’s editor, called with a proposition: Let’s put four more reporters on the story. Pringle said yes. And they agreed, according to “Bad City,” that “we would do this quietly — that is, without telling Maharaj and Duvoisin.”

They tapped Harriet Ryan, Adam Elmahrek, Matt Hamilton and Sarah Parvini, all of whom joined the effort, regardless of the potential risk to their careers.

Duvoisin and Maharaj both dispute how the team was formed and that it worked even briefly without their knowledge. “I knew and approved of their work from the beginning,” Maharaj said. Duvoisin concurred: “There was no time when I was not aware of it.”

The four new reporters on the team and the editor who led it independently allege that Maharaj and Duvoisin’s account is untrue. The team began in secrecy, they said, and neither of the top editors initially knew about it or sanctioned its operation.

When Pringle wrote the first version of the Puliafito story, he had not been able to find the young woman who had overdosed at Hotel Constance. He did not even know her last name.

This time around, Pringle figured out who she was. The team found her parents. And her brother, for whom Puliafito also allegedly provided drugs — when he was underage. Puliafito has denied giving drugs to Warren or her brother.

Eventually, Warren and her family agreed to talk, and so did others with whom Warren and Puliafito had illicitly partied.

The team put together a paper trail linking the USC medical school dean to all the players involved, a group the book describes as “much younger drug addicts and criminals.”

The family also agreed to share photos and videos of the group doing drugs together, according to the book.

For Dr. Carmen Puliafito and a group of younger people he befriended, life was a photo-op.

The reporting team handed in the next draft of the story at the end of March 2017. “Bad City” alleges that, at one point during the lengthy editing process, Pringle told the paper’s lawyer that, if the story was buried for months like the draft that had been killed, he’d file a complaint with the newspaper’s human resources department.

At the end of June, Pringle wrote to the company’s president of publishing and its chief legal counsel:

“This is to report actions by Davan Maharaj and Marc Duvoisin that I believe have harmed, and could further harm, The Times and the corporation. Our Code of Ethics and Business Conduct requires me to make this report.”

The company launched an investigation.

Duvoisin, according to “Bad City,” told the team it could not report that Puliafito regularly used drugs. Three days before publication, the book said, he deleted all but one reference to Puliafito supplying drugs to others.

Duvoisin said the company’s lawyer, Jeff Glasser, advised that those details be omitted because “the evidence didn’t really support ‘regularly’ using and that they should stick to a more conservative description of what the evidence was.”

Pringle said Maharaj and Duvoisin “ordered” the attorney “to go into the story and come up with the most conservative version. This was after [the attorney] had already signed off on it.”

Glasser declined to comment.

Duvoisin defends all his editing decisions on the Puliafito story. He said it was a piece “that had the potential to and did destroy the reputation, career and livelihood of a human being. That’s a circumstance that calls for the greatest precision, care, evenhandedness, concern for accuracy, concern not to overreach.”

The story was published on July 17, 2017. Although “Bad City” alleges it was not as strong as originally written, accolades and follow-up stories flowed.

And the internal investigation into Maharaj and Duvoisin continued. So many staffers wanted to talk to HR about the two men that interviews with them had to be scheduled on weekends and evenings, according to “Bad City.”

On Aug. 21, 2017, Justin Dearborn — chief executive of the Times parent company, which at that point was called Tronc — announced that Maharaj and Duvoisin had “left” the paper, along with several others.

The Times’ story on the management changes said the two men were “fired” in “a dramatic shake-up.” The company also terminated a deputy managing editor; an assistant managing editor; reporter Jill Leovy, who is Duvoisin’s wife; and Maharaj’s executive assistant.

Tronc described the personnel moves as a response to The Times’ flagging performance. Neither Duvoisin nor Maharaj was fired because of a conflict of interest in their dealings with USC, said the company, which immediately installed a Tronc executive as interim editor of the paper.

Puliafito was fired by the university shortly after the investigation was published. Nikias was ousted as president of USC after the Tyndall scandal, although he remained a professor. He negotiated a $7.6-million severance package and separately received a $3-million loan to buy a home in Manhattan Beach.

Sarah Warren and her family left Southern California and moved to Texas. According to “Bad City,” she began waiting tables and hoped to go to college.

Five months after the Puliafito investigation was published, newsroom employees formed a union, by a vote of 248 to 44. The Times was later sold to biotech billionaire Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong.

The newspaper is “in better hands,” Pringle said. And “journalism prevailed.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.