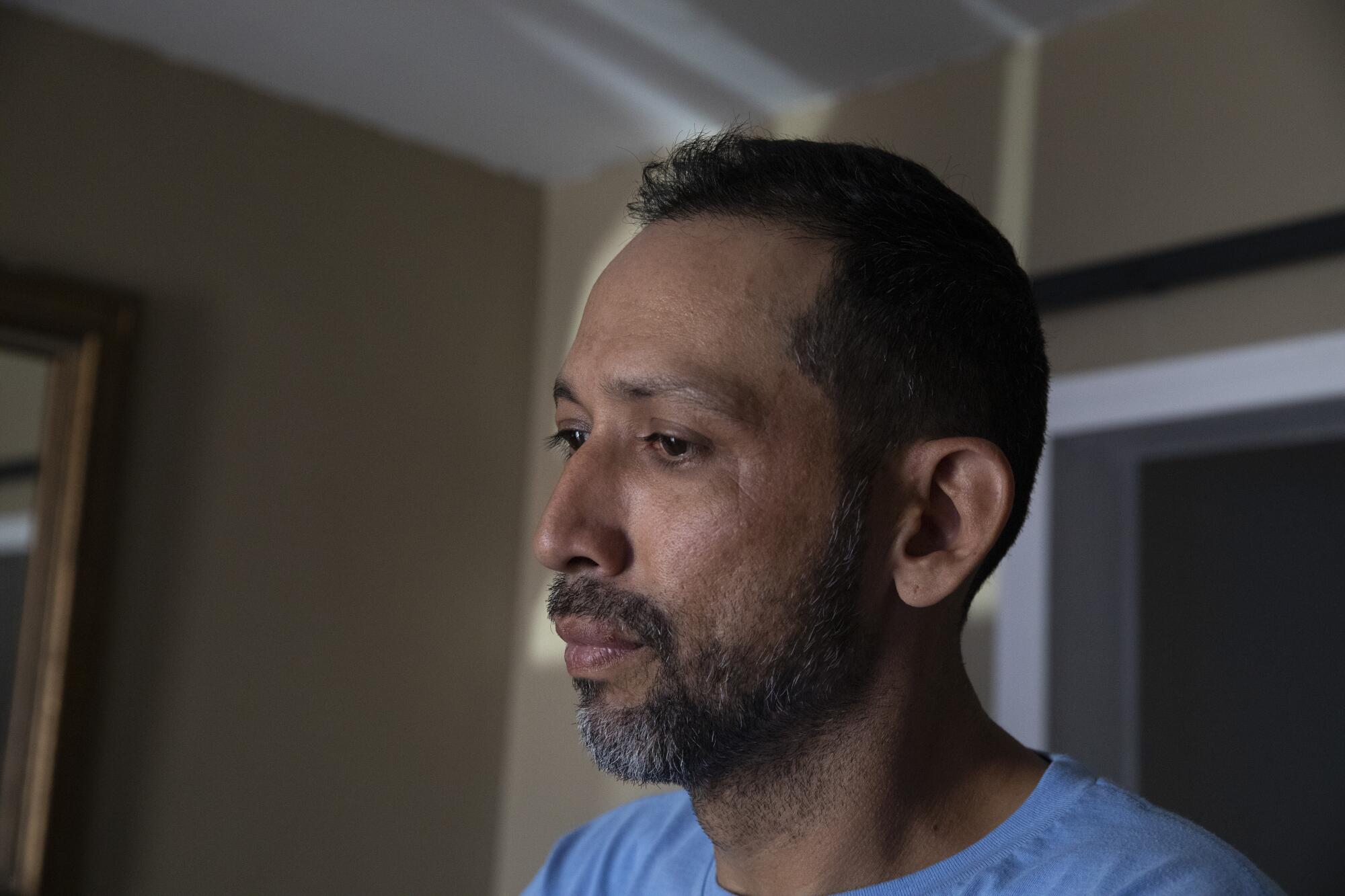

Eduardo Sanchez, a longtime San Diego resident, was among those caught up in the unannounced policy change after a court decision took away ICE’s guidance on discretion about deportations

- Share via

When Eduardo Sanchez showed up on a recent morning for a check-in with immigration officials in downtown San Diego, he assumed it would be like every other one he has had since 2017, when officials targeted him and his brothers-in-law for being undocumented.

He thought they would ask him if his address or phone number had changed and would make sure he was still complying with their requirements. They would check the status of his immigration case. Then he would head back to his Linda Vista home to be with his wife and two children.

But on Monday, July 11, Sanchez showed up for his check-in and within a matter of hours found himself deported to Tijuana.

That was roughly five days after a federal appeals court struck down Immigration and Customs Enforcement guidance prioritizing deportations based on significant criminal history or national security concerns.

“I didn’t know what to do,” said Sanchez, who has no criminal record, in Spanish. His voice caught with emotion as he recalled the moments he spent in an ICE holding cell waiting to be deported. “I was thinking a lot about how they were going to separate me from my family. It happened so suddenly.”

ICE did not respond to a request for comment.

ICE hasn’t announced any change in policy regarding which deportations it will carry out, but according to immigration attorneys, deporting someone like Sanchez is a clear break from previous policy.

Sanchez, 39, had a pending motion to reopen his case based on things that happened after his initial case was decided. Because of this pending motion, his attorney was shocked that ICE chose to deport him.

Sanchez said two other men in similar situations to his were deported with him, and immigration attorneys across the country, including in non-border states such as Oklahoma, have begun hearing from clients after ICE unexpectedly removed them from the United States.

The change could impact hundreds of thousands of people who have been issued removal orders by an immigration judge — the orders that give ICE permission to deport them — but who are still seeking other solutions to stay permanently in the United states.

No guidance

Under the Trump administration, people who had removal orders were often terrified of going to their next ICE check-in.

That’s because the administration told ICE officers to deport anyone and everyone that they could deport. Some people chose to take sanctuary in churches instead of showing up to their check-ins. Others made hail-Mary attempts to garner public support in the press. Many ended up deported.

When President Biden took office, he did so with a promise to focus on deportations based on criminal history.

In September 2021, Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas issued guidance to ICE about whom its officers should prioritize for deportation — people who officials considered threats to national security or public safety as well as those who recently entered the country without permission.

But the states of Louisiana and Texas sued, and a federal judge blocked Mayorkas’ memo. That ruling was upheld in early July by the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals.

A notice on ICE’s website assure that the agency is respecting the ruling.

“Until further notice, ICE will not apply or rely upon the Mayorkas Memorandum in any manner,” the notice says.

The Biden administration has appealed the decision to the Supreme Court, which has left the lower court’s decision in place for now but agreed to hear arguments in the case later this year. In the meantime, the case has left ICE officers with little guidance when it comes to whom to deport.

“It’s kind of led to this disarray where you think of ICE as an entire body nationwide, but it’s like a chicken with the head cut off right now,” said Miami-based immigration attorney Mark Prada. “I think they’re treating it as open season, and they’re deporting people as they wish now.”

In the past, said Oklahoma-based immigration attorney Lorena Rivas, ICE would generally give people checking in with them notice that they would be deported at a future date so that they had time to get their affairs in order.

She had a client deported without notice in recent weeks and has heard from other attorneys about such cases as well.

Life in California

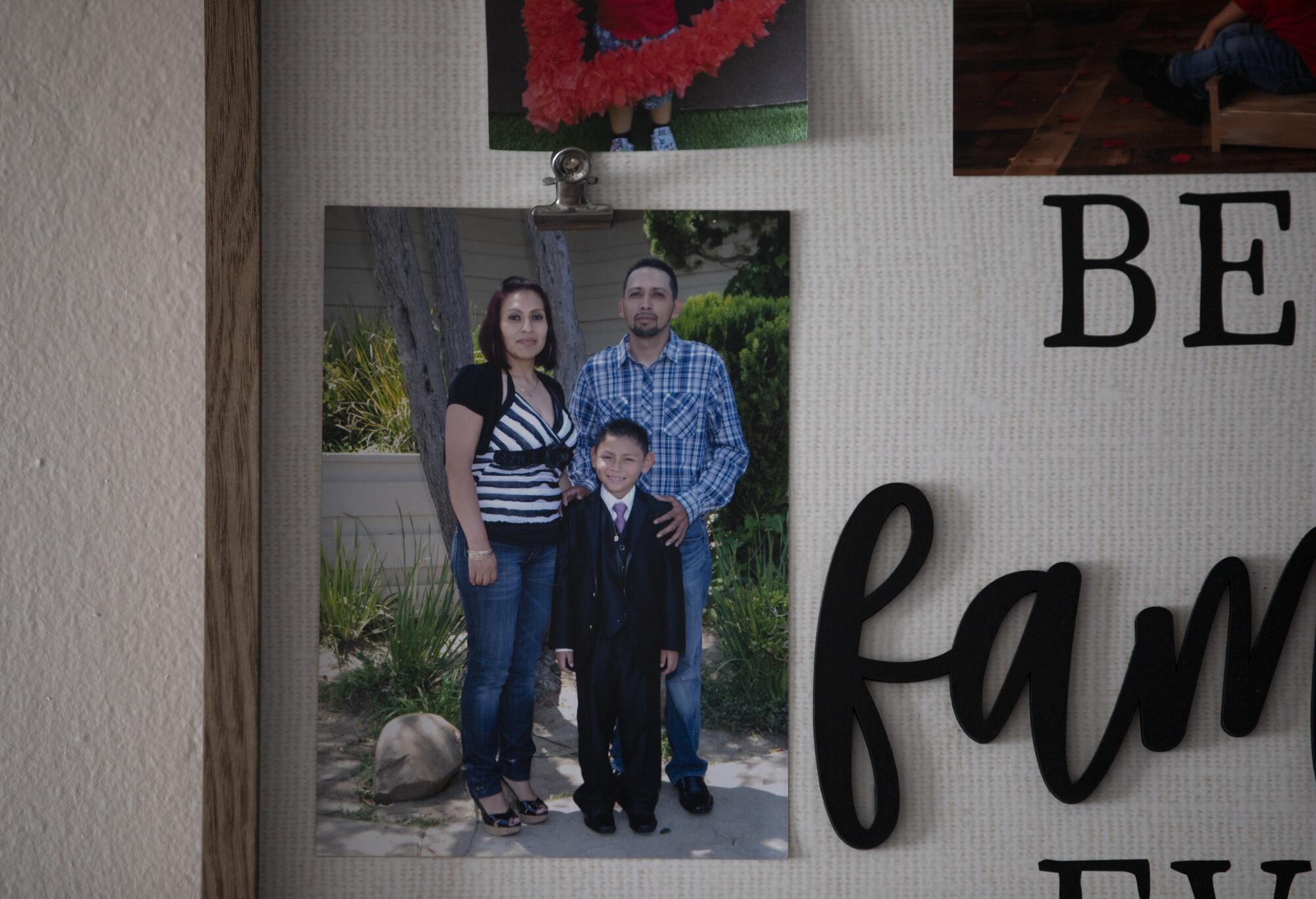

Sanchez came to the United States with his now-wife Patricia Osorio and several of her family members in 2000. The couple were both still teenagers — and minors — when they arrived.

Making ends meet with the work they could find as undocumented immigrants was tough, but they managed, coming of age and shaping their lives together. They had a son, Cristopher, who is now 18 and finishing high school.

“My life is in California,” Sanchez said. “There, I learned to work, to be a father.”

Sanchez worked for a time with his brothers-in-law at a car wash. Eventually he found a job painting cars.

Then came the Trump administration. The fall of 2017 was a busy time for the San Diego ICE field office. Its officers arrested more than 1,600 immigrants with no criminal history from October through December of that year — more than anywhere else in the country.

Sanchez was among them.

One day in November 2017 when he was on his way to work with Osorio, ICE officers stopped his car. He was given a notice to appear in immigration court and an ankle monitor, but he was allowed to stay with his family while he waited for his case rather than spending the time in immigration detention. He was required to check in periodically with ICE and follow their rules to monitor his whereabouts.

ICE came for Osorio’s brothers around the same time, Osorio said. One of them recognized the photo that ICE had of him as being from his driver’s license — all three had obtained licenses after California passed AB 60, which created a special driver’s license for undocumented immigrants.

Since then, they’ve wondered if those licenses were how the three men ended up as targets.

The number of children apprehended at the border, either traveling alone or as part of a family, has increased significantly since 2008, according to a new analysis

Sanchez showed up for his check-ins, and in immigration court, he applied for a program called cancellation of removal. That program allows longtime residents to request permission to stay if their deportation would cause extreme and unusual hardship to a U.S. citizen, in Sanchez’s case his child. The legal standard, which requires the immigrant to show hardship above and beyond the typical difficulties caused by deportation, is hard to meet.

Sanchez lost and was ordered deported in 2019. He appealed.

That appeal was dismissed by the Board of Immigration Appeals in 2021.

Meanwhile, his second son, Mateo, was born. And Sanchez was diagnosed with Graves’ disease, a condition that could lead to heart failure if he’s not able to get the proper medication.

On top of this, a cartel now controls the area where Sanchez is from in Mexico. After one of his family members refused to join, the cartel shot at the family home, and much of Sanchez’s extended family has since fled to request asylum in the United States.

With the help of a new attorney, Sanchez filed a motion to reopen his case on account of these changes in circumstance. The motion argues that an immigration judge should rehear his case for cancellation on account of his illness and the emotional hardship it would cause his children if he’s unable to get the care he needs to treat it while in Mexico. It also argues that he should be allowed to apply for asylum, which he has never done, based on the way his family has been hunted by the cartel.

The motion has been pending since September 2021.

Ginger Jacobs, an attorney with the firm representing Sanchez, said local immigration attorneys had an understanding with ICE’s San Diego Field Office that people like Sanchez would not be deported.

When he was taken into custody at his check-in, her firm was not notified, she said. Sanchez said he was allowed to call his wife but not his attorney. By the time Osorio got in touch with Jacobs’ office and an attorney there scrambled to file a request to pause the deportation, it was too late.

“It was so fast. It doesn’t seem fair to me,” Osorio said in Spanish. “We know what’s happened, that they took him and everything. But this, how it happened, I still can’t get it into my head.”

Sanchez thinks the speed of his deportation was intentional to keep anyone from being able to stop it.

“This is brand new,” Jacobs said. “This was not supposed to happen under a Biden administration, and maybe not even at all under any administration, especially when somebody has a motion to reopen based on asylum or asylum-like case reasons.”

In shock

The ramifications for Sanchez and others like him could be significant. Many of the ways to try to get permission to stay in the United States, including those he intended to apply for by reopening his case, require the applicant to be on U.S. soil.

Jacobs and her team are trying to find a way for Sanchez to return to his family and keep fighting his case. For now, Sanchez still hopes that he will be able to get back to the Linda Vista townhome his family rents.

Mateo is now 2 years old. When the boy was born, Sanchez organized his work schedule to be able to spend mornings together. The boy has been glued to him since, waiting for him to come back from work and following him around at home.

Sanchez and Osorio haven’t told Mateo that his father has been deported. He asks frequently for Sanchez, and Osorio tells him that Sanchez is at work.

Cristopher, the older son, doesn’t talk much about what has happened to his family, but it has clearly left a mark. When someone knocks at the door of the family home, Cristopher rushes to the window, face full of worry, to see who it is before opening.

He’s considering leaving his studies to help his mother pay rent. She works part time cleaning houses, but Sanchez was the main breadwinner.

Sanchez has found at least temporary refuge with a work friend who lives in Tijuana. Sanchez was deported with no more than $20 in his pocket and managed to call his friend while he was still close enough to the border to get cell service.

He barely leaves the house. He’s afraid that even in Tijuana the cartel might notice him and come after him.

“I’m still processing,” Sanchez said, sitting on the front porch of his friend’s home. “I can’t sleep. I don’t want to eat. It’s stressful to be in this situation.”

He spends most of his time watching TV and trying not to think. At night, he inflates an air mattress in a spare room his friend has used for storage.

Osorio is still in shock. Mateo’s 3rd birthday is coming up in September. She knows the boy will expect a cake, a celebration. But she’s not sure whether that’s financially — or emotionally — possible anymore.

Morrissey writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.