A Pendleton Marine, an Afghan interpreter and the meaning of ‘always faithful’

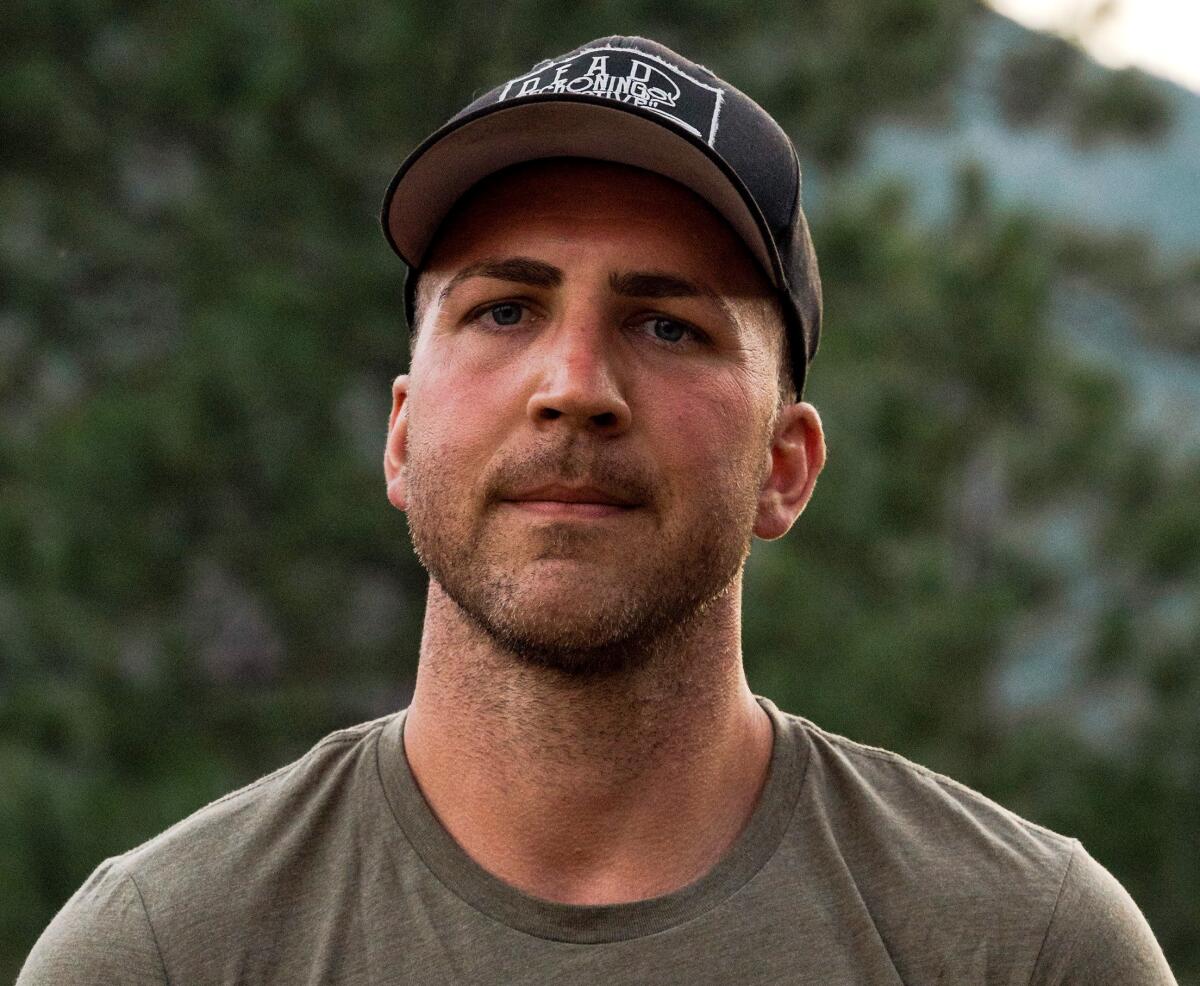

The Latin motto of the U.S. Marines, “Semper Fidelis,” translates into English as “Always Faithful.” Ask Maj. Tom Schueman and Afghan interpreter Zainullah Zaki about it and they will tell you this: The word that matters most is always.

“It’s easy to be faithful sometimes,” Schueman said. “It’s easy to be faithful when things are going your way. It’s easy to be faithful when you’re standing on a beach in San Diego, 75 degrees and sunny.”

This story is for subscribers

We offer subscribers exclusive access to our best journalism.

Thank you for your support.

Not so easy to be faithful when an improvised explosive device, or IED, goes off in the kill zone that was Afghanistan’s Helmand province. One explosion knocked Schueman down and out in late 2010. Zaki could have run for cover. Instead he picked up Schueman’s rifle and stood watch over him until help arrived.

Not so easy to be faithful when the 20-year Afghanistan war ends, the Taliban returns to power, and Zaki’s role helping the Americans brings him death threats. Schueman, back home in the U.S., could have shrugged his shoulders. Instead he worked around the clock to help the interpreter flee Afghanistan with his wife and four children.

“My family is safely in America today because Maj. Tom and I stood by each other at all times,” Zaki said.

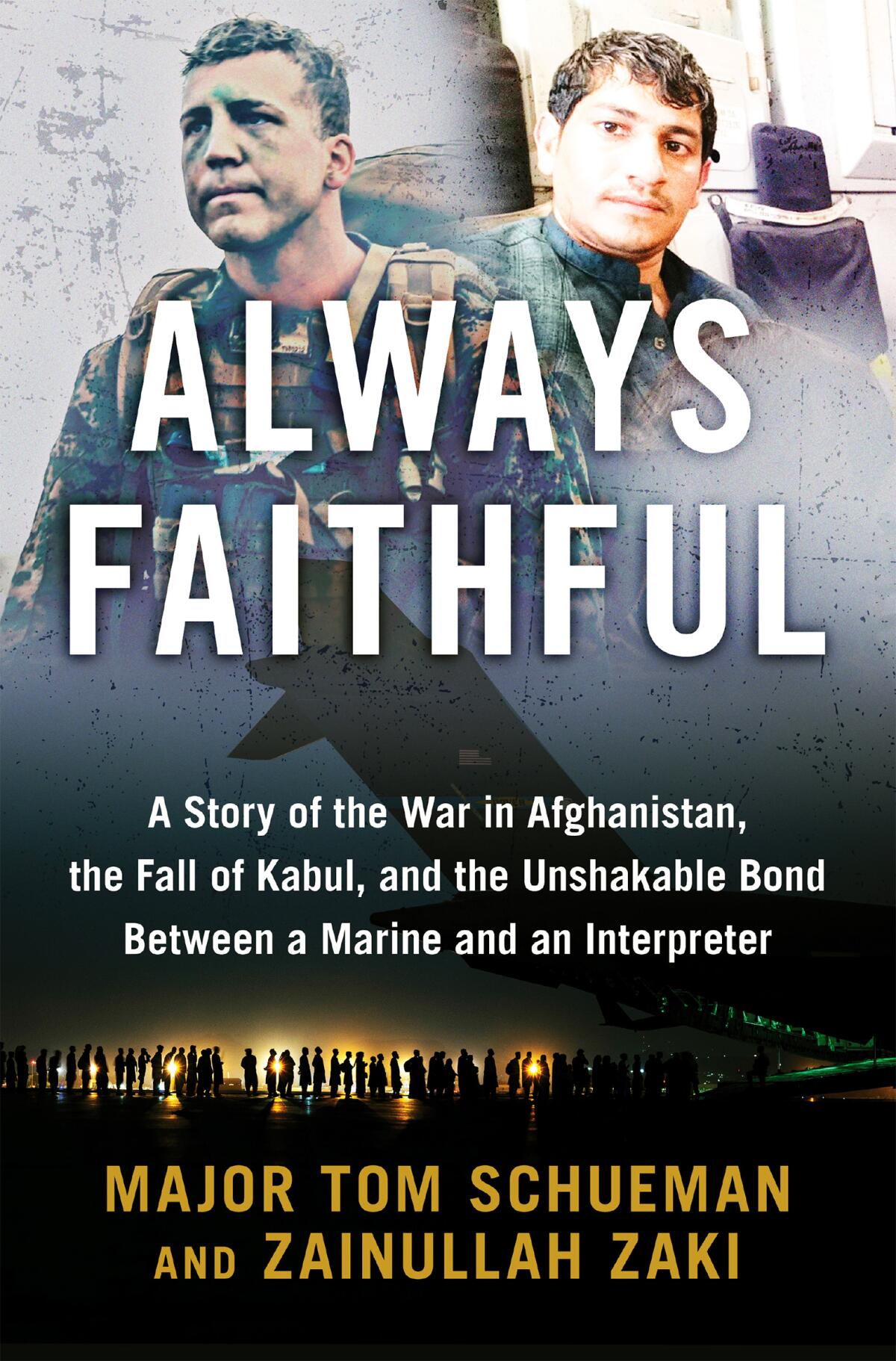

Their unexpected friendship forms the backbone of a new book, “Always Faithful: A Story of the War in Afghanistan, the Fall of Kabul, and the Unshakable Bond Between a Marine and an Interpreter.”

Published earlier this month, and told in alternating chapters from the viewpoints of the two men, the book offers a deeply personal look at war and its aftermath — the idealism, the danger, the lingering physical and moral injuries.

Much of it involves the 3rd Battalion, 5th Regiment out of Camp Pendleton: the Darkhorse Marines. They went into Sangin in the fall of 2010, saw combat almost every day for three months, and suffered the heaviest casualties of any battalion in the war: 25 dead and 184 wounded (34 of them losing at least one limb).

They also killed a lot of Taliban fighters — 25 for every one they lost, according to the book.

Schueman was a lieutenant then, in charge of the battalion’s 1st Platoon, Kilo Company. Arriving in Afghanistan, he was filled with “an aggression and a predatory spirit that made the hunting of armed men seem like an aspiration.” He didn’t have to wait long.

On his company’s first patrol, they got fired on before everybody was even out of the base.

‘How badly did I want it?’

The book arrives as people in the U.S. and Afghanistan are marking the one-year anniversary of the chaotic and deadly exit from Kabul by American forces.

Zaki and his family managed to get out amid the desperation and confusion of the final days, guided to a particular gate at the airport via cellphone text messages from Schueman and others.

The family flew to Qatar, then Germany, and eventually settled in San Antonio, where relatives live. They are awaiting a ruling from U.S. immigration authorities about whether they can remain.

After two tours in Afghanistan, Schueman spent several years teaching English literature at the Naval Academy and the Naval War College, where, as he writes in the book, “I had to reconcile my love for the heat of combat and my abhorrence of its waste.”

He’s since returned to Camp Pendleton, to a new assignment with the Darkhorse Marines.

In a recent joint phone interview with the Union-Tribune, Zaki and Schueman talked about their time together, the bonds they forged, and the question that haunts many who fought in Afghanistan: Was it worth it?

They met on Oct. 14, 2010, at a forward operating base in Helmand province. After training as an interpreter, Zaki had flown there, the first airplane ride of his life. He was 20 and got assigned to Schueman’s platoon.

Zaki grew up on a farm in Kunar province, with the Taliban in charge and restricting what people could see, hear, do and wear. “There was nothing to make us a nation except our hopes,” he writes in the book.

After 9/11, the U.S. invaded, and brought with them new schools, health clinics, cellphone networks and roads. Zaki attended school regularly for the first time and “began to see a future for myself beyond our fields.”

Jobs were scarce, though, and when he heard about work as a translator for the U.S. forces, he signed up. He said he knew it would be dangerous. He was OK with that.

“Life in the new Afghanistan meant people had to be willing to take risks to have better lives for their families,” he remembered thinking. “If I would not die for it, how badly did I want it?”

Schueman, who was in his mid-20s, brought his own hopes and fears to Sangin, a place of dirt and blowing dust and irrigation canals that stretched from the Helmand River to fields of opium and corn.

He’d grown up in Chicago, the son of a single mother who worked for the police. His father did time in prison in Georgia. He was super competitive in sports and academics — a boat with a powerful engine, he said, but no rudder. The military gave him direction and a way to pay for college.

“I’ve never been the smartest or most talented guy in any room I’ve been in, but I am relentless — for better, or for worse,” he writes in the book.

On their first patrol together, Zaki was told to step where Schueman did, to avoid IEDs. Within minutes of starting out, enemy fighters started shooting at them. Zaki froze in place while the Marines around him hit the ground and returned fire. A corpsman reached up, grabbed the back of Zaki’s body armor and pulled him to the ground.

“I never got to speak to an Afghan that day,” Zaki recalled. “I just got shot at by them.”

A promise made

The months went by and they grew closer.

Schueman wanted to keep a brave face for the Marines in his company, so there were things he wouldn’t say out loud to them. But he would to Zaki, during downtimes.

“We both wondered if we would survive Sangin,” the interpreter said. “We both wondered if we would see our families again. We both wanted to know whether what we were doing had value to the world.”

Getting shot at every day, seeing friends get blown up or shot — it became “a life of brutal sameness,” in Schueman’s words. “Sadness became simple numbness.”

As the translator, Zaki talked to village leaders about what they wanted from the Americans, and what the Americans wanted from them. They knew that some of the people were lying, Zaki said, and that some had probably been the ones shooting at them on other days.

Afghans, Zaki said, knew they had to figure out which way the wind was blowing and follow it.

“Power shifts suddenly in Afghanistan,” he writes. “Who you know and support matters more than who you are. It has always been that way.”

Schueman saw in Zaki someone who was willing to do more than just talk. There was the incident with the IED, which knocked Schueman out. He awoke to find Zaki standing over him, rifle in hand. Another time, Zaki ran through a field to a house and tackled a Taliban fighter who was getting ready to call in an ambush.

“He wasn’t just there to do a job,” Schueman said. “He was one of us, willing to risk his life in defense of the country.”

They were together until April 2011, when Schueman’s deployment ended. He made Zaki a promise: “Anything you need,” he said. “Anything.”

Zaki cried as the helicopter took off. “To live the way we had each day, not knowing if we would live or die or be mutilated, created a love that made it hard to accept that I would probably never see him again.”

Five years went by. The men settled into lives in their home countries. They got married, had children, tried to keep at bay the demons war had left them.

Zaki had a family to support, but after the U.S. bases shut down, few job prospects. (He said he couldn’t afford the bribes necessary to win the favor of those doing the hiring.) He started receiving death threats, sometimes posted on his front gate, because he had worked for the Americans.

In 2016, he applied for a Special Immigration Visa, open to Afghan interpreters, and entered a maze of paperwork and bureaucracy. He found mostly dead ends.

And then he found Schueman, on Facebook.

A mad scramble

Still on active duty, assigned now to the support side of the Marines, Schueman got a master’s degree in English literature at Georgetown University and then taught at the U.S. Naval Academy and the Naval War College. He explored ideas about moral injuries, talked openly about helping veterans process the trauma they’d experienced in combat and adjust to life back in the U.S.

He spent a lot of time thinking about the Marines who had been killed in Afghanistan, and others who committed suicide after they’d come home. He didn’t want Zaki to be another casualty.

Getting him out of the country, though, proved harder than he’d imagined. Just filling out the forms was problematic because of cultural differences. Many Afghans only use one name. They don’t always know what their birth date is.

Schueman struggled to locate the people who needed to sign the paperwork proving that Zaki had worked the required number of months for U.S. forces. He sent emails to addresses that worked in 2011 but were invalid now.

And Zaki’s case wasn’t the only one under review. Thousands of Afghans had worked for coalition forces during the war. Many of them wanted to come to the United States, too.

Months went by, then years. Schueman turned to social media and the news media for help. He patched together a network of sources and allies, in the U.S. and Afghanistan.

It all came to boil last August as the U.S. pulled out of Afghanistan and the Taliban overran the country. Schueman told Zaki to take his family to Kabul. On Aug. 18, 2021, a flurry of text messages directed the family to a secret gate at the airport.

Zaki was instructed to put his 6-year-old son on his shoulders so American forces could pick them out in the crowd. They were waved to a door and pulled inside. The gate slammed shut behind them as other Afghans rushed forward.

“I’m so happy, inside,” Zaki texted Shueman.

“So happy you’re safe,” Schueman texted back. “See you in America.”

A year later, they’ve had time to ponder whether the war in Afghanistan was worth it. Both believe it was.

“People in both our countries should remember the sacrifices that were made” to try to make Afghanistan a country where people enjoy everyday freedoms, Zaki said. “If the next generation understands the importance of service, they will do what it takes, and that makes me very excited.”

Schueman pointed to the lives lost and the injuries suffered on both sides and said it feels disrespectful to measure that cost against concepts like “democracy,” “freedom” and “prosperity” in an Afghanistan ruled by the Taliban.

For him personally, he writes in the book, “I was granted the opportunity to see young Americans at their finest, to see men barely out of boyhood accept the reality of their mortality and yet run to the sound of the guns.”

And he met Zaki.

“I lost a war,” he writes, “but gained a brother.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.