Pour more money and planning into renewable energy — and keep Diablo Canyon running if needed

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — The dust-up at the state Capitol over nuclear power is the direct result of politicians either setting unrealistic goals or failing to plan — or both.

Most of the blame falls on Gov. Gavin Newsom and his predecessor, Jerry Brown, although the Legislature certainly shares in it.

Brown issued an executive order in 2018 setting an ambitious goal of California becoming carbon neutral by 2045. Now, Newsom is asking the Legislature to make that goal legally binding.

Newsom also wants to adopt more aggressive clean electricity targets and tighter limits on greenhouse gas emissions leading up to 2045.

To hit those marks, California must gradually turn exclusively to renewable power sources such as solar, wind, geothermal and hydroelectric.

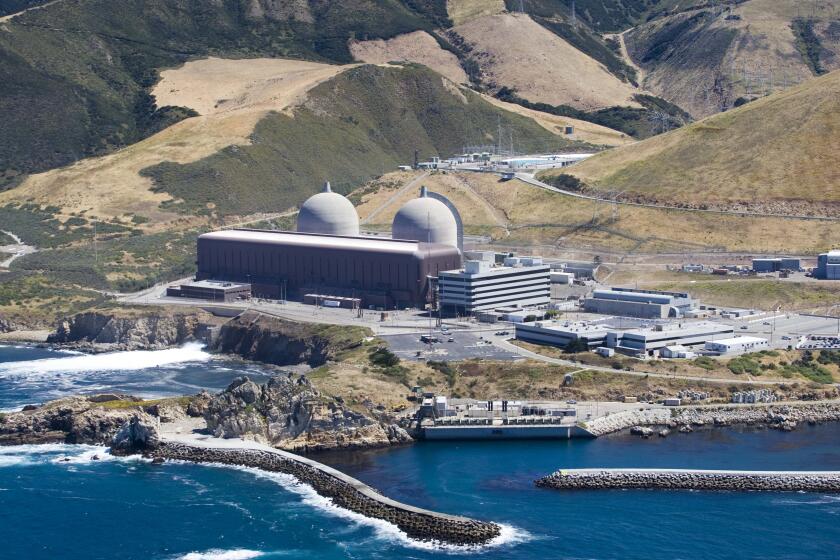

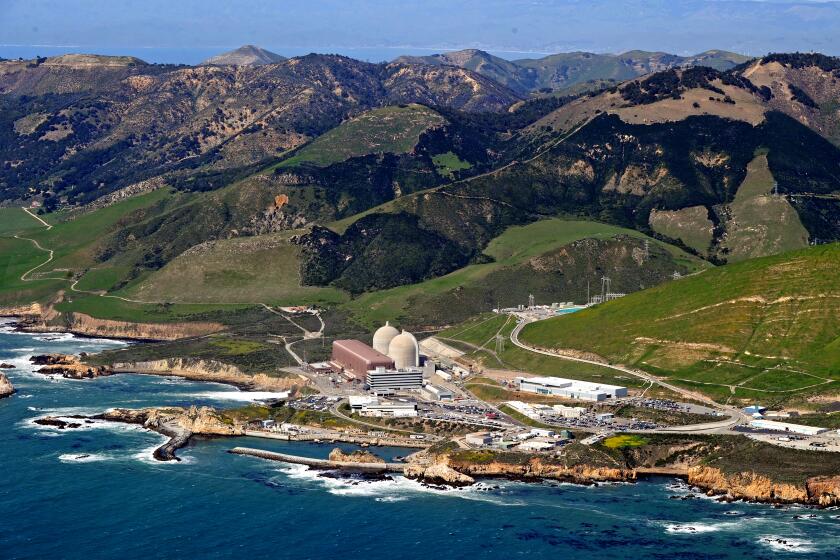

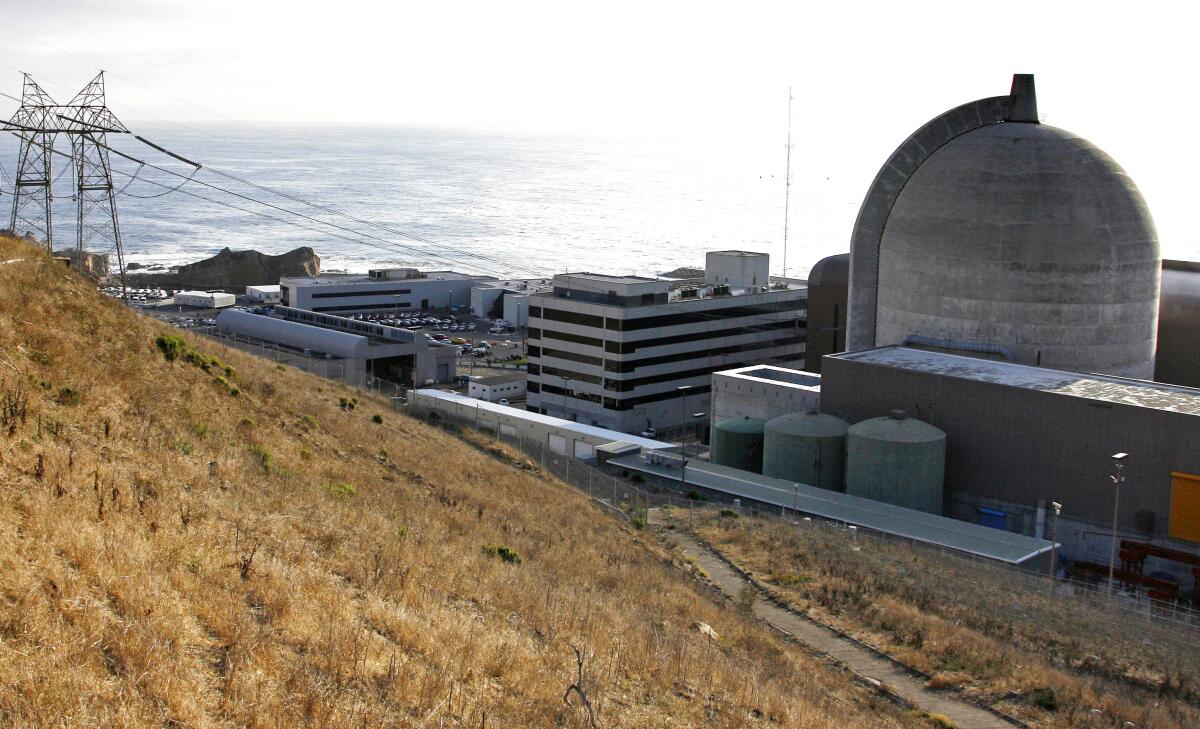

But wait: We haven’t developed nearly enough renewable energy to replace our carbon-emitting natural gas power plants — or, Newsom says, the carbon-clean Diablo Canyon nuclear plant on the Central Coast near San Luis Obispo.

It’s California’s last nuclear plant and is scheduled to shut down in 2025.

“A lot of these folks think that if you just declare a goal, it’s self-executing. Well, it’s not,” says Dan Richard, an engineering consultant who formerly headed the California High-Speed Rail Authority.

“You can’t wave a magic wand and have these things appear. It’s not like flipping a light switch. The reality is we’re not on a pace to meet the goals. The pace literally needs to be two to three times faster.”

Richard is executive director of Carbon Free California, an independent group pushing renewable energy. It strongly supports Newsom’s proposal to extend Diablo’s life for 10 more years.

The urgent problem is not about failing to meet goals but avoiding politically embarrassing blackouts when Diablo stops generating power. It currently produces 8.5% of California’s electricity and 15% of the carbon-free power.

The plant could stay open through 2035 under a proposal from Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Hardly anyone loves nuclear power. It has caused public jitters for decades, since the 1979 Three Mile Island accident and the release of a popular movie, “The China Syndrome.”

There’s a particularly scary aspect about Diablo: nearby earthquake faults. But they’re discounted by Diablo advocates.

“There’s always a risk, but I have very high confidence in Diablo,” says Peter Yanev, an earthquake engineering consultant. “Because of its design, it’s likely to be one of the safest places to be in an earthquake.”

What especially scares Newsom is the likely prospect of blackouts after Diablo is shuttered. They’d probably come on his watch.

“Do any of these [legislators] really want to own the next blackout?” Richard says. “The ghost of Gray Davis is hovering over all of us.”

Davis was recalled as governor in 2003 largely because of a lengthy statewide energy crisis. It was created by Texas power pirates such as Enron but handled awkwardly by Davis.

“It’s crazy to close down an existing zero-carbon resource in hopes something will show up to replace it,” Richard says.

Newsom is urging the Legislature to pass a bill enabling Diablo to stay open for another decade. But many lawmakers are ticked because he waited until the last minute, Aug. 12. Their two-year session ends Wednesday. Legislative leaders don’t like a governor jamming them.

Diablo is the most contentious issue they’re facing.

A coalition of environmental groups — including the Sierra Club and Natural Resources Defense Council — strongly opposes Newsom’s proposal.

A Q&A about Diablo Canyon: why it’s targeted, what it does to the ocean, why Gov. Gavin Newsom wants to keep it open, and more.

“A dangerous and costly distraction to achieving our shared [zero-carbon] goals,” the coalition asserted in a letter to the Legislature.

The central piece of Newsom’s legislation is a $1.4-billion loan to Diablo’s owner, Pacific Gas & Electric Co., to help pay for deferred maintenance needed to keep the plant operating and the process of seeking a federal license renewal.

But it’s anticipated that the loan wouldn’t need to be repaid because the Biden administration has a $6-billion kitty that states can draw from to help keep nuclear plants open. Handing out the federal money will be Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm, who was raised in the Bay Area and advocates keeping nuclear plants alive to fight climate change.

“The expectation is that the feds end up paying the cost of most of this, if not all,” says Newsom spokesman Anthony York.

The deadline for applying for that federal money, however, is coming up fast: Sept. 6. That’s why the loan authorization and a commitment by the Legislature to Diablo is so urgent, York says. The state can’t apply for the federal money without legislative action.

“If we don’t act now, we close the door,” he says.

Some Assembly Democrats have floated a vague proposal to let the plant close as scheduled and spend the $1.4 billion on increasing renewable energy and modernizing the power grid.

York told the Associated Press that proposal felt like “fantasy and fairy dust.”

Frankly, I dismiss the idea because no legislators are willing to attach their names to it. They’re apparently afraid to be seen bucking the governor.

It appears that Newsom and legislative leaders are heading toward a halfway solution: taking steps to keep Diablo operating but not making a firm commitment.

“It wouldn’t be a final decision. It would be an opportunity to make a final decision,” says Sen. John Laird (D-Santa Cruz), who has been leading a compromise effort. “Maybe a quarter of the $1.4 billion.

“We want to kick the tires on the program.”

There’d be an “offramp” if the federal money was denied. And another offramp if enough renewable energy showed up.

We should pour a lot more money — and planning — into renewables.

And keep Diablo open if that’s what is needed so the lights and air conditioners work — and electric vehicles are charged.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.