Newsom enjoys his most successful legislative session yet with wins on climate, Diablo Canyon

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — Despite lots of private grousing about him, Gov. Gavin Newsom emerged a big winner at the end of the California Legislature’s two-year session.

The griping was over his waiting until the last minute before sending legislators an ambitious package of climate-fighting proposals.

Most of it was passed, nevertheless, demonstrating the awesome power of a governor — especially one from the same party that controls the Legislature. In this one-party rule, one person generally does the ruling when he wants: the governor.

But not always.

Sources requesting anonymity told me that some Assembly Democrats loyal to Speaker Anthony Rendon (D-Lakewood) blocked one major climate bill that Newsom sought. They just refused to vote. Their purpose allegedly was to punish the governor for delivering the measure too late for careful scrutiny. Rendon himself voted for the bill.

Legislators don’t like to be jammed by a governor, even one from their own party.

Games are always played in the Legislature, particularly on the last night of a session.

An important gun control bill died just before midnight when it fell one vote short of the two-thirds majority needed for passage. It would have imposed strong limits on carrying concealed weapons. California’s old limits were ruled unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court.

One assemblyman who normally supports gun controls has a running feud with the Senate author of the bill and refused to vote on his measure.

“I wish I was powerful enough to single-handedly kill any bill. There are 120 members of the Legislature and many of them did not support this bill. That is why it failed,” Assemblyman Patrick O’Donnell (D-Long Beach) replied in a written statement when I asked about his abstention.

“The author’s staff couldn’t answer basic questions about the bill. I’m not going to pass something … that may not be constitutional.”

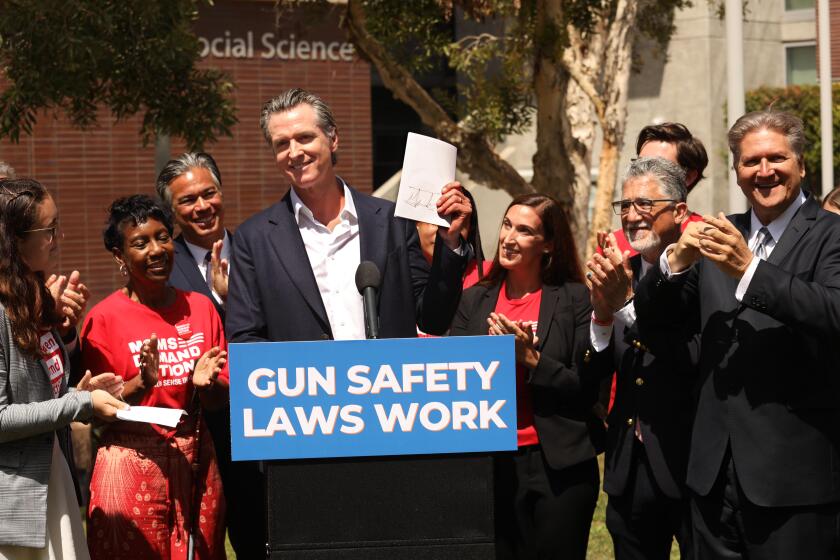

Gov. Gavin Newsom notched a series of wins in the final days of the legislative year, but his action on some bills frustrated progressive organizations at the state Capitol.

But then O’Donnell finished with a comment that indicated more was involved. He said the author “needs to look in the mirror as to why this bill failed.”

The author, Sen. Anthony Portantino (D-La Cañada Flintridge), is chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, which has killed several O’Donnell bills.

Portantino said he’ll reintroduce the bill when the next Legislature convenes. By then, O’Donnell will have returned to being a full-time high school government teacher.

“The governor was disappointed that the bill failed,” said Newsom spokesman Anthony York.

But Newsom scored several major victories as the legislative session ended — the biggest being his bill to keep the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant open for an extra five years.

Many Democrats would have preferred to close the plant in 2025, as was agreed in 2016 by owner Pacific Gas & Electric Co. and environmental groups. Environmentalists worried about earthquake safety and wanted California to focus more on developing renewable energy.

Newsom supported closing the plant back then. But he recently concluded that by 2025, California won’t have enough renewable energy to replace Diablo, a carbon-clean power source that produces 8.5% of the state’s electricity. There’d probably be blackouts — shutting off lights, air conditioning and electric vehicle chargers.

Newsom deserves credit for flip-flopping — usually considered a political no-no — and having the guts to change his mind. Of course, he also feared being blamed for summer blackouts.

Most Democratic legislators bought into that view — and so did Assembly Republicans.

It was strange and unprecedented to watch a Republican legislator be the floor jockey of a Democratic governor’s bill. Assemblyman Jordan Cunningham (R-Templeton) was wisely selected to handle the bill on the lower house floor because Diablo is in his district.

Teresa Romero, president of the United Farm Workers union, requested a meeting with California Gov. Gavin Newsom on Cesar Chavez Day. But it didn’t fit Newsom’s schedule, columnist George Skelton writes, because he headed that day on a spring-break family vacation.

Most Republicans followed in support — 16 of 19 voting “aye.” Wonder if there’d be less partisanship if Democrats occasionally cut Republicans in on the action.

The measure passed easily, 69-3. Rendon didn’t vote.

“The speaker was supportive of the initial legislation to close Diablo Canyon and generally maintains that position today,” said his spokeswoman, Katie Talbot.

In the Senate, there was the usual partisan divide. Sen. Brian Dahle, the underdog Republican gubernatorial nominee from tiny Bieber in Lassen County, declared he was “not going to bail the governor out” from past poor decisions. He accused Newsom of setting climate change goals without adequately planning how to achieve them.

But that’s what the governor was trying to do with this climate package.

The bill breezed through 31-1.

The measure was significantly altered from Newsom’s original proposal because Sen. John Laird (D-Santa Cruz) insisted on it. Diablo is in his district.

The plant extension was cut from 10 years to five. A $1.4-billion loan to PG&E for maintenance and upgrades will be handed over incrementally, starting with $350 million. The loan is expected to be repaid with federal grants anyway. The California Coastal Commission must approve the extension. Newsom wanted to cut out the agency. There’ll be $1.1 billion spent on green energy.

The legislation “only does the minimum things necessary,” Laird said.

Newsom also muscled through several climate bills. One will legally bind California to become carbon neutral by 2045. And to ensure that 100% of California’s electricity is noncarbon by 2045, there’ll be interim targets of 90% by 2035 and 95% by 2040.

The bill that failed — and was maybe sabotaged — would have set a target of cutting greenhouse gas emissions 55% below 1990 levels by 2030. The goal now is 40%. But there’s some doubt even that can be reached.

Newsom also scored with legislation barring new oil wells within 3,200 feet of homes, schools, hospitals and other “sensitive” places. He had to buck strong oil industry opposition.

It was Newsom’s most successful legislative session.

But next year, assuming reelection in November, he’ll start being a lame duck with diminishing clout. State tax revenues are bound to decline in this screwy economy. So, enjoy the moment, governor.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.