L.A. County on track to join Newsom’s sweeping mental health plan a year early

- Share via

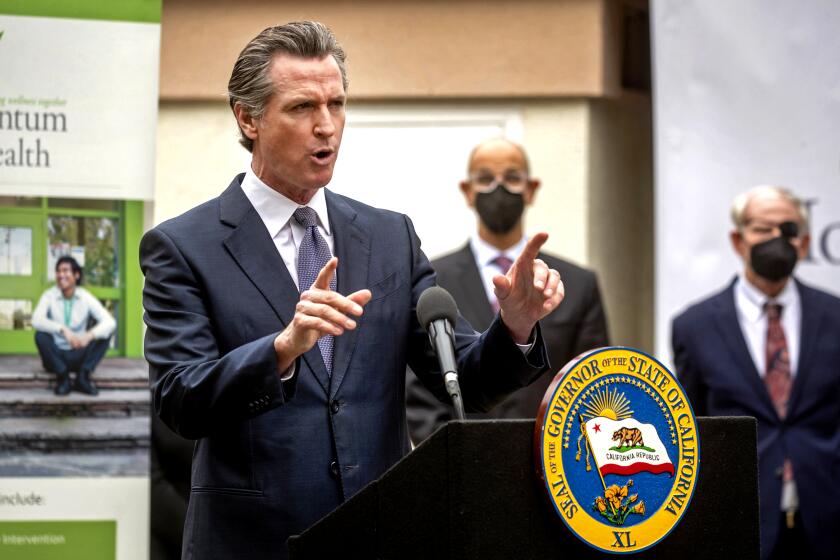

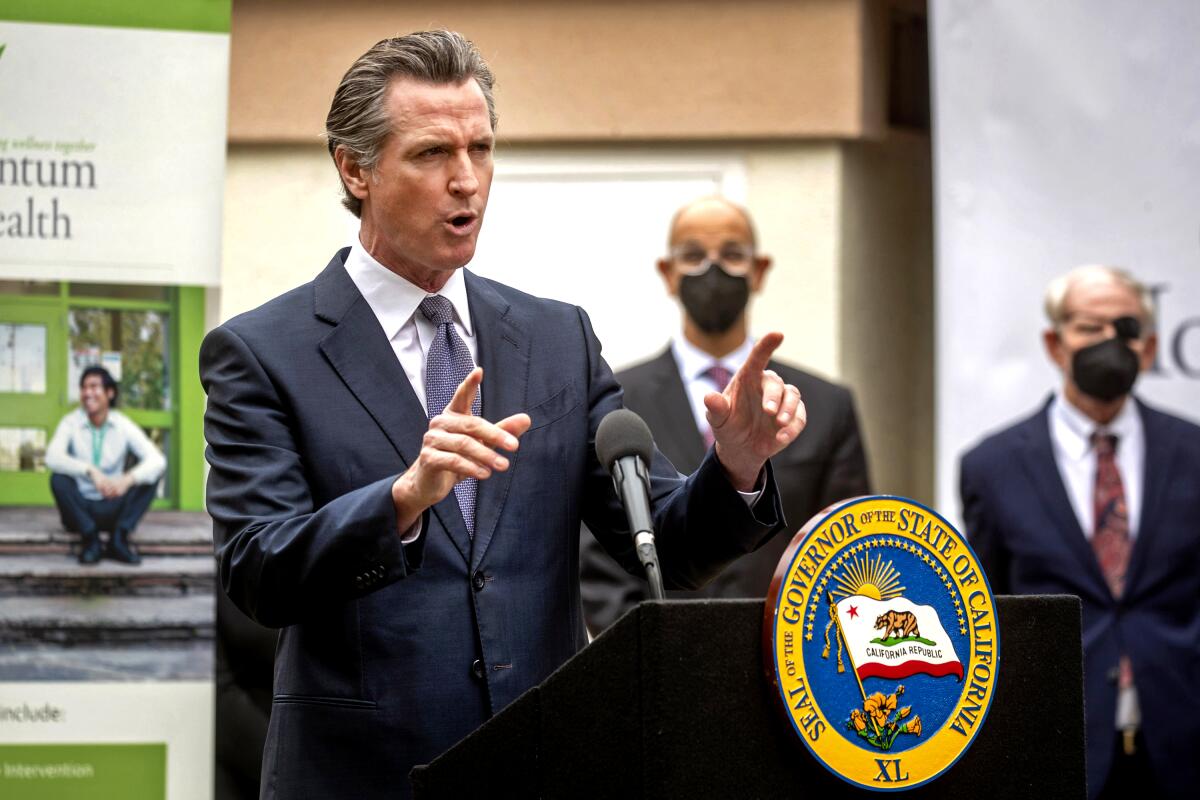

Los Angeles County is on track to join the first wave of counties this year launching a sweeping plan backed by Gov. Gavin Newsom to address severe mental illness by compelling treatment for people who are in serious crisis.

The governor’s office announced Friday that Los Angeles County would kick-start the new program known as CARE Court (for Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment) by Dec. 1, a year earlier than expected.

“CARE Court brings real progress and accountability at all levels to fix the broken system that is failing too many Californians in crisis,” Newsom said in a statement. “I commend Los Angeles County leaders, the courts and all the local government partners and stakeholders across the state who are taking urgent action to make this lifesaving initiative a reality for thousands of struggling Californians.”

However, a key question remained unanswered Friday afternoon: whether the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors needs to vote on the plan for the county to join the program. A voting majority of the supervisors — Hilda Solis, Janice Hahn and Kathryn Barger — have expressed support for starting CARE Court this year in a public statement.

When signed into law, the CARE Act identified seven counties for the initial rollout on Oct. 1: Glenn, Orange, Riverside, San Diego, San Francisco, Stanislaus and Tuolumne. The rest of the state, including Los Angeles County, has until December 2024.

Los Angeles County had planned to join that later rollout, said Lisa Wong, interim director of the county’s Department of Mental Health, which will be the administrator of the CARE Court program.

“This year was going to be a very busy year for us,” she said, citing a number of initiatives that were already on the books for 2023 including Hollywood 2.0, a pilot program to provide services and care in a part of the city where homelessness and mental illness are especially acute.

Although her agency did not know “with certainty” that L.A. County would be added to the first cohort before this week, Wong understands the urgency.

“Whether we were in the first or second cohort, there will always be challenges,” she said. “The fact is that people who need this help are on the street, suffering and not getting the care that they need. There is never a convenient time to implement this kind of large-scale program, but the level of need out there is so great that we can’t put it off any longer.”

Adding Los Angeles County, the state’s most populous county, to the first phase of the new program could have consequences for Newsom’s ambitions to address one of California’s most vexing problems: the huge number of people on the streets who struggle with addiction and mental illness.

By some estimates, close to 40% of people living on the streets are experiencing severe mental illness, a substance abuse disorder or both. More precisely, the California Policy Lab at UCLA determined that just over 4,500 people living on the streets of the county have a psychotic disorder like schizophrenia, and that number includes only those who have received outreach services.

The sudden inclusion of L.A. County is a measure of the urgency of the state’s homelessness crisis, particularly in Los Angeles, and comes with some risk. While the other seven counties have been formulating their CARE Court plans for nearly four months, Los Angeles County is on a fast track, and any difficulties implementing the program invite further criticism.

Supervisor Lindsey Horvath told The Times that she is “concerned by the rushed decision to join the program,” which demands robust infrastructure and services to be successful.

“Without proper investment and clear direction, this system will run the risk of breaking the promises that we have made to L.A. County voters to deliver real, meaningful progress and change,” Horvath said.

Supervisor Holly Mitchell similarly urged caution against rushing into an agreement this year, instead calling for a “robust discussion” on the decision at a board meeting next week.

“It’s imperative that we have clarity on how the courts and county will implement this program with sufficient funding to be successful,” Mitchell said in a statement.

The county Department of Mental Health has been assured that it will receive appropriate funding from the state to move into the first cohort, said Wong.

“All of us want this to be successful,” she said. “We have concern for this highly vulnerable patient population, and we know something has to be done.”

Newsom’s announcement represents the latest in a series of actions taken in the city and county of Los Angeles in recent weeks to address the crises of mental illness and homelessness that have overtaken the city.

Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass declared a state of emergency in the city on her first day in office on Dec. 12, and the county supervisors followed suit nearly a month later. The declarations will help expedite services for the tens of thousands of unhoused people in the region.

“I support bringing CARE Court to our county. It allows us to be on the ground floor of a new program where a lot of processes and implementation details still need to be worked out,” Barger said in a statement. “Our county needs to have a seat at the table so we can effectively bring healing to individuals living with debilitating mental illness on our streets.

“We need a coordinated and consistent approach to help these individuals, and CARE Court is poised to help us meet that mission. Severe mental illness doesn’t resolve itself.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom signs CARE Court proposal into law, a sweeping plan to order mental health and addiction treatment for thousands of Californians.

When Newsom introduced the CARE Act in March, his proposal was met with early resistance.

The legislation was initially meant to address the state’s homelessness crisis through the auspices of California Health and Human Services and be administered by county agencies. But requiring these agencies to address homelessness — with sanctions if court-ordered housing is not provided — was a hard sell, said Dr. Veronica Kelley, director of behavioral health services for Orange County.

So the CARE Act evolved, and when the legislation was signed in September, it focused not so much on homelessness but on helping individuals with schizophrenia and associated disorders. Many behavioral health departments then decided it would be in their interest to be in the first set of counties to implement the program.

When a funding measure for the CARE Act was passed in the fall, it allocated $88 million in new funding for implementation of the court-based system.

In his January budget proposal unveiled on Tuesday, Newsom set aside another $52 million to continue helping counties and courts implement the new program, with plans to ramp up funding to nearly $215 million by fiscal year 2025-2026.

Those numbers don’t yet account for Los Angeles County, said Jason Elliott, Newsom’s deputy chief of staff and top advisor on housing and homelessness. Instead, the governor plans to increase funding in a revised budget plan that comes out in May. Billions of dollars more are available to fund CARE Court through existing housing, homelessness, behavioral and mental health programs, according to the administration.

The Legislature has until June 15 to approve the budget.

The administration estimates that 7,000 to 12,000 individuals would currently qualify for CARE Court, though not everyone would have to be homeless. Newsom’s administration contends that CARE Court wasn’t crafted to solve unsheltered homelessness, but rather to help some of the state’s most vulnerable and mentally ill find the necessary treatment and behavioral health services, and for many, that could include housing.

Chabria: ‘No treatment until tragedy’ is our mental health system. CARE Court could change that

Gov. Gavin Newsom has proposed civil courts to help people with severe mental illness. Critics call it ‘forced treatment’ — but that misses the point.

Proponents have hailed it as an innovative approach that will help stem the flow of those with severe mental health concerns into hospitals and jails, while critics have called it a violation of personal freedoms. Organizations such as Disability Rights California and the American Civil Liberties Union spent much of the 2022 legislative session trying to block CARE Court from passing.

Given the challenge of implementing the CARE Act, initially excluding counties like Los Angeles made sense, said Rod Shaner, who served as medical director for the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health from 1996 to 2018.

“This is a common way to start a large program like this,” said Shaner. “If there are large unforeseen problems with immediate full-scale implementation of the CARE Court, then they could cause dire statewide consequences. A more gradual phase-in allows potential problems to be identified when they are small enough to be more easily managed and corrected.

Elliott argued that including Los Angeles County will help other counties who have until 2024 to put it in place.

“What we’re doing now isn’t working,” Elliott said. “CARE Court is big and bold, and we’re going to assume and plan for success. We’re going to be optimistic. I think L.A. County joining this program early is an indication that there’s a lot of confidence on the local level.”

The CARE Act — like other attempts to legislate treatment for severe mental illness in California — is constrained by the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act.

Among the most conspicuous challenges facing counties as they implement CARE Court is uncertainty over the financial responsibility of insurers, who are required to pay for court-ordered treatment in instances where the individual has coverage.

“Guidance to insurers about compliance has not yet been issued,” said Shaner.

Despite widespread interest in ending homelessness, Newsom has faced intense opposition from some local governments over whether CARE Court is the best solution.

During his budget news conference Tuesday, Newsom renewed his commitment to CARE Court.

“This is life and death. People are dying in the streets in the name of compassion and these stale arguments,” he said. “Unprecedented support. I want to see unprecedented progress.”

Times staff writer Rebecca Ellis contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.