Three’s not a crowd. Meet the co-presidents of the union behind the hotel workers’ strike

- Share via

In a red-shirted sea of hundreds of striking hotel workers marching through downtown Los Angeles on the Fourth of July, Ada Briceño, Susan Minato and Kurt Petersen were just faces in the crowd.

They spread across the width of Olympic Boulevard — Minato on the left, Petersen to the right and Briceño in the center — about five rows back from a massive banner that read “ON STRIKE.” Briceño walked alone. Minato held her arms in a “V” for Victory whenever passing cars honked. Petersen gently pushed marchers back with caution tape to shield them from oncoming traffic.

Sometimes, the trio clapped along to the deafening beats of pans and drums. Mostly, they stayed silent and took in the scene, part of the largest hotel workers’ strike in U.S. history.

Hotel workers in Los Angeles and Orange counties voted to authorize a strike during the height of tourism season if talks don’t result in a new contract.

When the march stopped in front of the JW Marriott Los Angeles, they left the masses and climbed onto a makeshift stage.

“Buenos días — good morning — everybody!” Briceño said, her blue-rimmed glasses notable from far away. “I’m one of three co-presidents of Unite Here Local 11. How do we feel?”

The crowd cheered — not just for the cause but also the leaders before them.

Briceño, Minato and Petersen have run Unite Here Local 11 — which represents over 32,000 workers in Southern California and Arizona — since 2017 and will be sworn in for their third term later this month. They head what is believed to be the only union in U.S. labor history to have more than one president at the same time.

“I don’t even know what to say about it, because it’s so unprecedented,” said University of Rhode Island labor historian Erik Loomis. He noted that American unions have historically relied on charismatic leaders “that stay in office forever. But however the three of them work and manage all of their egos — and I imagine there’s the occasional blowup — obviously it’s working.”

The walkout by Local 11 of Unite Here is affecting about 20 hotels. Although they are staying open, their guests can expect the hotels to be noisier and possibly trim the amenities.

Under the watch of the triumvirate, Unite Here Local 11 has continued a tradition of fusing labor and political power kick-started by former president, now-state Sen. Maria Elena Durazo in the 1990s that transformed L.A. politics — and has arguably made it more influential than ever.

The union, which represents workers across 60 hotels in the Southland, successfully pushed for a 2018 ballot measure in Long Beach that required hotels with more than 50 rooms to provide so-called panic buttons to workers in case a guest tried to sexually assault them. It convinced politicians to raise the minimum wage for hotel workers in 2021 in West Hollywood and to reduce workloads for hotel employees in Los Angeles last year. In Anaheim, members gathered enough signatures to force a special election this fall on whether to raise the city’s minimum wage for hotel workers to $25.

Minato was part of the most recent Los Angeles City Council Redistricting Commission; Briceño is the chair of the Democratic Party of Orange County. Unite Here’s political action committee spent around $364,000 to support the successful L.A. council run of one of its organizers, Hugo Soto-Martinez, who attended the Tuesday rally.

As the leaders addressed the crowd, they offered glimpses into how they split up the work.

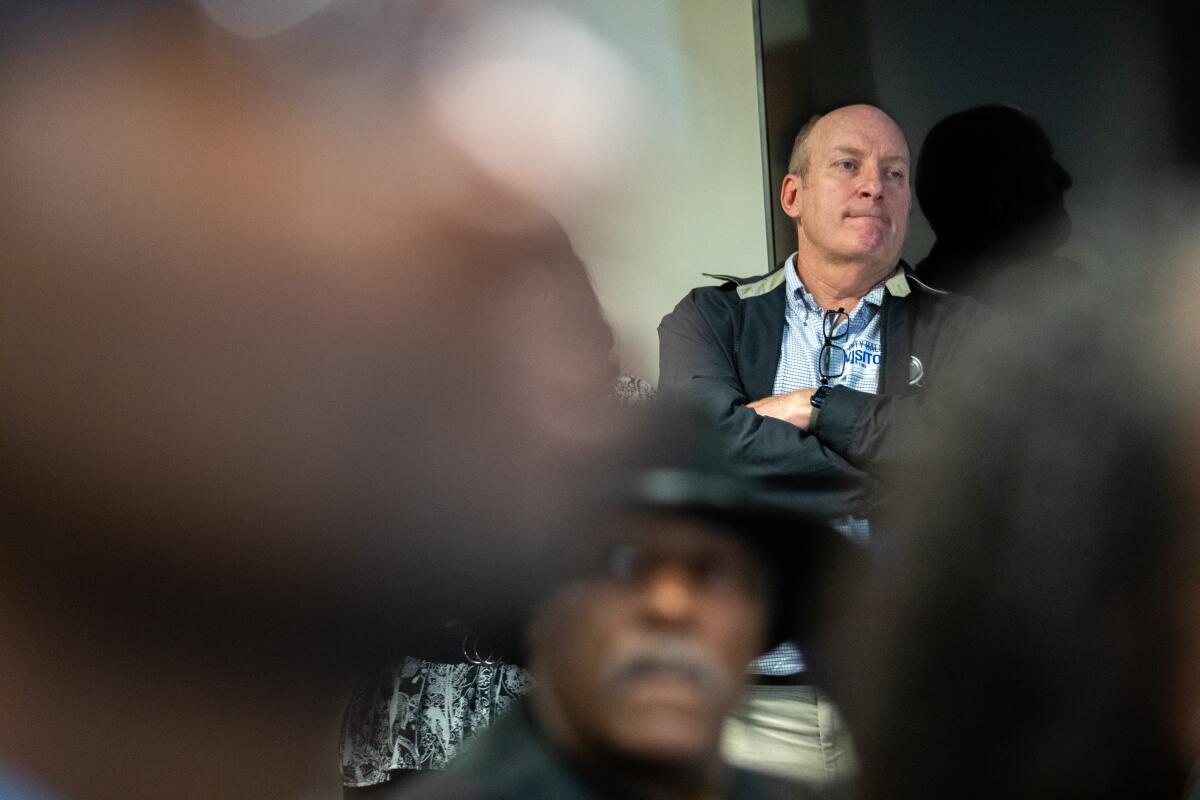

Briceño, as comfortable with the rank and file as she is with elected officials, spoke the longest. Minato, a former lawyer who spearheaded a Unite Here political campaign that helped flip Arizona to Joe Biden in 2020, offered short remarks. Petersen, looking like an uncle on vacation in a long-sleeved shirt, cream khakis, sneakers, sunglasses and a baseball cap, led the crowd in a call-and-response chant that name-checked the 19 hotels across Southern California whose workers had walked off the job Saturday.

“It’s a lot,” Petersen cracked, his voice hoarse from days of chanting. “It’s mucho.”

After the strike ended the following day, I interviewed the three via Zoom. Briceño and Minato spoke from their home offices; Petersen joined us from his cellphone as he drove back from the Fairmont Century Plaza Hotel. He had just met with Unite Here members who claimed they weren’t being allowed back to work.

“They’re feeling more powerful than ever,” he told us as his video froze. “Because they stood toe-to-toe with the boss, and they won.”

The union is pushing for an immediate $5 hourly wage increase and $3-an-hour raises for each of the next three years. The hotels have responded with an offer of a $2.50-an-hour raise over the first 12 months, going up to $6.25 an hour after four years.

More strikes could follow throughout the summer, Unite Here promises.

Even though they spoke of the past week as a “blur,” the three leaders showed no signs of fatigue. They hyped up one another to me like the longtime friends they are. When I disclosed that Loomis described their power-sharing agreement as “unprecedented,” everyone smiled.

“It’s true,” Minato replied.

“The idea that you share power can be scary to leaders,” Petersen added. “But frankly, given what’s in front of us, there’s really no other option but to share leadership and allow other people to step up and fight.”

“I don’t know how easy it would be for a top leader of a union to accept [other co-presidents] unless it was already up and down the organization,” Briceño said. “It works for us — it doesn’t feel foreign for us because that’s the way we learned how to do it.”

The three met in the 1990s, when each worked at different Southern California locals for Unite Here’s predecessor, the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union — Briceño in Orange County, Petersen in Santa Monica, Minato in Los Angeles. Briceño was a Nicaraguan refugee whose family ended up in San Pedro. Minato, who is Japanese American, grew up in New Jersey, where her parents resettled after being unjustly incarcerated by the U.S. government during World War II. Petersen, a Chicago native, attended Yale Law School but never got a degree after becoming involved in the farmworker movement.

“They were complete believers in rank-and-file power,” Durazo remembered of her first impressions of the three. “That was the commonality. That’s what they were looking for.”

By then, Durazo and her husband, the late Miguel Contreras, had transformed Local 11 from a traditional top-down union to one with a flattened command structure to better tap into a new generation of immigrant Latino workers. “Usually, there’s such a finite number of leadership positions that people lose their motivation,” she said. “We had to have this continuous opportunity available to new leaders.”

Briceño, Minato and Petersen plugged into this system under Durazo, then continued their rise after she left in 2006 to head the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor. By the time Durazo’s successor, Thomas Walsh, retired in 2017, Briceño was secretary-treasurer, Minato the executive vice president and Petersen a vice president.

The three received Walsh’s blessing to take over his position together.

“I gotta admit, I don’t know who to go to sometimes,” Durazo said. “Usually, you go to the person with the top title. But those outside of their day-to-day, we’re the ones thrown off. That’s not the worst thing in the world if you’re being successful.”

When Soto-Martinez went to Florida to moonlight at another Unite Here local, he told a fellow organizer about the co-presidency — or co-co-presidency. “And he told me, ‘What the hell?!’”

The council member said workers had always viewed Briceño, Minato and Petersen as “very powerful, but they didn’t have the titles. When they got it, it wasn’t going to be, ‘Yo soy el chingón’ [I’m going to be the badass]. It was very clear to us! ‘This is the way we do things different.’ A level of transparency and solidarity reinforced from the bottom to the top.”

The three generally split responsibilities based on their strengths — Briceño on the ground, Minato behind the scenes, Petersen as the “strategy genius” — but seamlessly trade off tasks as needed. They check in every Friday with a meeting that used to include lunch, pre-pandemic — “I guess we should go back to being live with each other,” Minato joked.

They have run unopposed in the past two elections. After the first one, members also approved their suggestion to change Unite Here’s bylaws and make the co-president model permanent.

Briceño admitted that it can “get contentious and difficult. But we pull through because we believe in the collective, and we believe in what we’ve done together.”

“I’m thinking we move to five next time. In case we get into an argument, you have to have an odd number,” Petersen deadpanned.

Minato and Briceño laughed.

“We have never had,” Briceño said with a grin, “a two-to-one kind of situation.”

Times staff writer Helen Li contributed to this report

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.