- Share via

Sherry Hill had lost track of her daughter, which wasn’t a surprise. She lived on the street and was so caught up in cycles of mental illness and addiction that she didn’t care that she could have a better life.

The younger woman’s father had died two years ago and left her with more than enough money for housing and support.

Hill and her second husband, Mel, were now administrators of the trust, and they needed to contact her. But the couple were in their 70s, living near Fresno, and in no position to start searching.

They called the police in Pasadena and filed a missing person report, but when the officers found her, Hill recalled, they said there wasn’t anything they could do. Her daughter, who was 52, had a right to be left alone, to be homeless if she wanted, and didn’t warrant a psychiatric hold.

Frustrated, Hill made a call that she wished wasn’t necessary. It was her last resort.

Vicki Lucas answered.

Part private investigator, part street clinician, Lucas makes her living helping families reconnect with loved ones lost to homelessness, mental illness or drugs. The job means searching the streets while coordinating treatment options with mental health teams, psychiatrists and residential facilities.

She calls herself a crisis interventionist, and her clients are often parents like Hill, frustrated by the inability of California’s behavioral health care system to help them or their children. With no other options, these parents have turned to an emerging field that is capitalizing on the current crisis of homelessness and mental illness. Insurance does not cover the service, but for families who can afford it, hope is worth the price.

Because the field is unregulated, it’s unclear how many interventionists are working in California. They operate like private contractors with contacts on speed dial who can expedite treatment, extend involuntary holds and secure conservatorships. They say their methods are above board, but they also say that the ends justify the means because the existing system is failing so many people.

In addition to Lucas, The Times interviewed four others, two of whom declined to speak on the record. While interventionists coordinate with psychiatric outreach teams associated with local police departments in order to facilitate an involuntary hold, those teams also declined to comment.

Lucas, who had worked with the Hill family before, agreed to help. For $6,000 plus expenses over six months, she would try to find Hill’s daughter, have her placed on an involuntary hold in accordance with state law and taken to a facility where she could be treated.

But there were no guarantees.

Last year, Lucas had gotten the woman into a private hospital in Pasadena, where she stayed for 10 days before walking out. (Hill asked that her daughter’s name not be used in this story to protect her privacy.)

Hill knew the odds were long. Only police and mental health professionals can institute an involuntary hold, and adults who are not on a conservatorship have the right to refuse treatment.

But Hill was grateful for the help. She wanted to make amends with her daughter, apologize for missteps in their past, and felt that Lucas was her only chance.

“Thank God there is someone out there for us to hire,” Hill said. “I’m not an expert in this system or how it works, but I know the problems we have run into.”

Lucas began her search one morning in May on Colorado Boulevard in east Pasadena, a warren of boarded-up storefronts, empty parking structures, strip malls and motels. With graying hair cut close in a high fade, she walked with an easy confidence, a hand in her pocket and the other holding her phone.

You can help someone get on the path to housing — and make your voice heard on issues of housing and homelessness. Learn how with Shape Your L.A.

She started at an auto body shop. The plan was to find Hill’s daughter, assess her condition and see if she would agree to treatment. The key, she said, was to build trust, one meeting at a time.

She showed a photograph of Hill’s daughter to one of the detailers. He shook his head.

“This is the hardest part,” Lucas said, as she poked her head around a corner where a restaurant kept its dumpster.

Intervention was once a buzzword for families and friends desperate to confront a loved one whose dependency on drugs or alcohol had taken a toll on their relationships.

Meetings often took the form of ambushes and laid out the emotional consequences of living with addiction. A successful outcome might lead to professional help, an unsuccessful outcome to greater alienation and division.

Applying this model to mental illness comes at a time when psychoses have become more entangled with addiction. Many interventionists like Lucas bring their experience in the addiction recovery field to their work on the street.

While training, certification and membership in a professional organization are available, Lucas says she is largely self-taught and believes her experience as a recovering addict makes her effective. She says she has clients around the country and manages a network of close to 140 private contractors to assist her in averaging two to three interventions a week.

“When I see people who are addicted to drugs and out of their minds, I feel like they don’t have the ability to make good choices,” she said. “This is why they are where they are, and it’s my responsibility to get them in a safe place, get them stabilized and then talk to them about their choices.”

Her straight talk strikes a sympathetic chord among those like Hill who feel that California’s behavioral health laws veer too far toward protecting the civil liberties of severely mentally ill people when humanitarian need is so great.

Nearly 30 years ago, Hill said, she watched helplessly as her daughter began to exhibit erratic behavior associated with an identity disorder. Trauma in her childhood led to drinking and drug use, and the young woman slowly lost touch with her family including a husband and three children.

Now her father’s money offered the hope that these bonds could be repaired.

Lucas approached a middle-aged man sitting on the edge of a planter outside a 7-Eleven. He wore red sneakers and had a blanket pulled over his head. He looked up and recognized Hill’s daughter from the photo. He pointed down Colorado Boulevard.

“By the liquor store,” he said.

Lucas gave him a few cigarettes and a bag of Jolly Rancher gummies.

Since starting her company, Equanimity Interventions, in 2017, Lucas has watched her field grow more crowded at a time when the ranks of social workers are stretched thin.

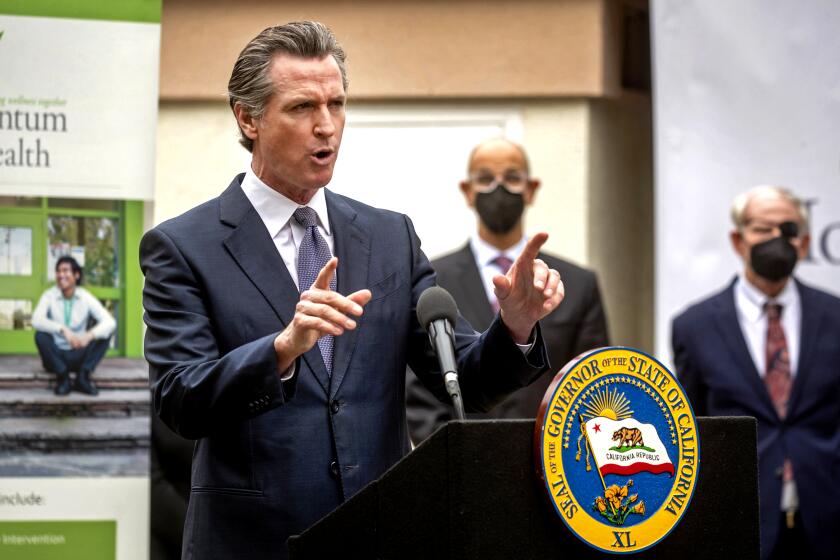

Gov. Gavin Newsom has promised reform, but legislation like the CARE Act — which gives families the means to secure treatment for a loved one — and an effort to amend the state’s conservatorship law will take time to have an effect. Until then, in addition to interventionists, a network of attorneys, addiction specialists and former healthcare professionals are stepping up for families left angry and bewildered by the bureaucratic and legal constraints that keep police, hospitals and courts from helping them.

During the 2020-21 fiscal year, more than 120,000 adults in California were admitted to psychiatric facilities for evaluation and treatment, according to statistics compiled by the state’s Department of Health and Children’s Services. Of that total, 72,000 were released after 72 hours, while 30-day holds were authorized for only 3,300 patients.

“This is the big failure of our system,” said Lee Blumen, an Orange County attorney who specializes in mental health law. “These numbers show why we have a need for more than what’s provided.”

Blumen, who worked with the public defender’s office handling conservator cases, has consulted with interventionists. Some fly in from out of state to provide their services. Some provide case management as well as outreach, and some, he said, are better than others.

“Families come to them desperate. They say they will pay anything to help their child. I hate hearing that,” he said. “They are vulnerable to those who will take advantage of them.”

Lucas is no stranger to that desperation. She maintains close relationships with a group of psychiatrists and hospitals amenable to conservatorship, particularly for clients who can pay out of pocket, and her tactics on the street — securing information in exchange for cash or cigarettes, calling crisis teams only when psychoses are most conspicuous — can be unconventional.

Dr. Timothy Pylko, a psychiatrist who has worked with Lucas, described some stratagems that interventionists use to persuade people with mental illness to accept treatment as “theater.”

“Sometimes,” he said, “that means tricking them into going into the hospital” but without what might be considered “kidnapping.” The work is bound by the state’s conservatorship law and picks up where some agencies (“skittish and not well trained”) leave off.

“We have seen patients over the years compelled to get treatment come out on the other side and live meaningful lives,” he said.

From Lucas’ perspective, all’s fair if it means saving a life. She has seen the outcome of untreated mental illness — destitution, violence, incarceration and death — and as angry as many families are at the current system, so is she.

“Do I think it’s unethical?” Lucas said. “No. I feel the unethical s— is in all those hospitals that failed these people over and over like they’re just numbers, in and out. ... There’s so many failures in psychiatric hospitals, so many people not doing the job and seeing it through, and so many people that die as a result of it.”

But the methods hardly matter for families who live in fear of one day receiving a phone call from a hospital, jail or morgue.

One mother, who requested that her name not be used, said she received that call earlier this year from a hospital’s psychiatric ward letting her know that they had to release her son, who was being treated for schizophrenia, because a court had determined that he no longer qualified for an involuntary hold. He could either go home or enter a shelter.

Neither option was suitable, and the mother reached out to Lauren Arborio, whose company — Connections in Recovery — arranged for a mental health companion to meet the young man and stay with him.

Within 24 hours, the young man’s mental state had deteriorated enough to reinstate the hold, but Arborio’s support, if brief, was relief for a family forced to find a quick solution for helping their son.

“She saved our lives,” the mother said. “We wouldn’t have known what to do without her.”

When Arborio started providing mental health services in 2011, she thought she would focus on substance abuse and alcoholism. “I never thought I would be getting the calls that I’m getting now — a lot of schizophrenia,” she said.

She charges $250 an hour for a consultation and up to $2,500 a day for live-in support.

Before leaving the 7-Eleven parking lot, Lucas noticed a woman sitting outside wearing dark glasses with the hood of an olive sweatshirt pulled over her head. Lucas recognized her and offered her a cigarette.

“I don’t smoke,” Hill’s daughter said.

Lucas asked if she wanted to talk to her mother. She said yes, and Lucas called, put the phone on speaker and handed it over.

“Hi, honey. How are you doing?” Hill asked.

For 15 minutes, mother and daughter spoke as if no time had lapsed between them. The younger woman had a number of questions that seemed to follow an invisible logic: Are you dying? Are you still married to your husband? Is he good to you?

And they discussed the money.

“I’d rather you keep it for me, so I know it’s in a safe place,” her daughter said, adding, “Do you have a gun to your head or anything?”

“No,” Hill said. “I just want you to know how much I love you, and I’m sorry for all that you’ve been through.”

Afterward, Hill realized that her daughter wasn’t ready to be helped.

“I don’t want to force her to go somewhere,” Hill said. “I would rather be a steady gentle loving presence, than a force to put her somewhere where I don’t think she would stay.”

Lucas understood but wondered if they could afford to wait.

Two weeks later she was back on Colorado Boulevard. The middle-aged man with red sneakers pointed down the street, where she met four men living in a motor home. As they were talking, she noticed Hill’s daughter a block away. She was with a young man in a red sweatshirt pushing a shopping cart filled mostly with empty wrappers and trash.

Seven counties will open their CARE Courts on Oct. 1. The state has estimated that 7,000 to 12,000 people will qualify for a treatment plan.

Lucas stopped them and offered cigarettes. When the young man asked for money, Lucas said she would buy him a meal, but he declined.

Hill’s daughter struggled to light the cigarette. Her profile, partially hidden again with dark glasses and a hoodie, was gaunt and thin. Her companion pulled out a lighter and fired up her smoke before walking away.

Lucas turned to her. “I’m just wondering if you want to get off the street,” she said and offered to take her to see Pylko. “We could get you a house with your money. No hospital, just treatment.”

“I love Dr. Pylko,” she said.

Lucas saw an opening. “And meds,” she said, gambling on the prospect of legitimate drugs.

“Those meds don’t do s—,” the daughter said, soon restless, eyeing her companion as he got farther away. “I get better on the street.”

Lucas understood.

“I’ll give you a week to think about it,” she said. “Then I’ll be back.”

Lucas watched her walk away. She was encouraged but also felt time was running out. Hill’s daughter, she guessed, weighed no more than 80 pounds.

“She’s starving,” said Lucas, who returned to Pasadena in early June and again in July.

On each occasion, Hill’s daughter was nowhere to be found.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.