SAN DIEGO — In the shadow of Petco Park, Steve Garvey was greeted as a Padres hero who played alongside baseball legend Tony Gwynn and helped the team to its first World Series appearance.

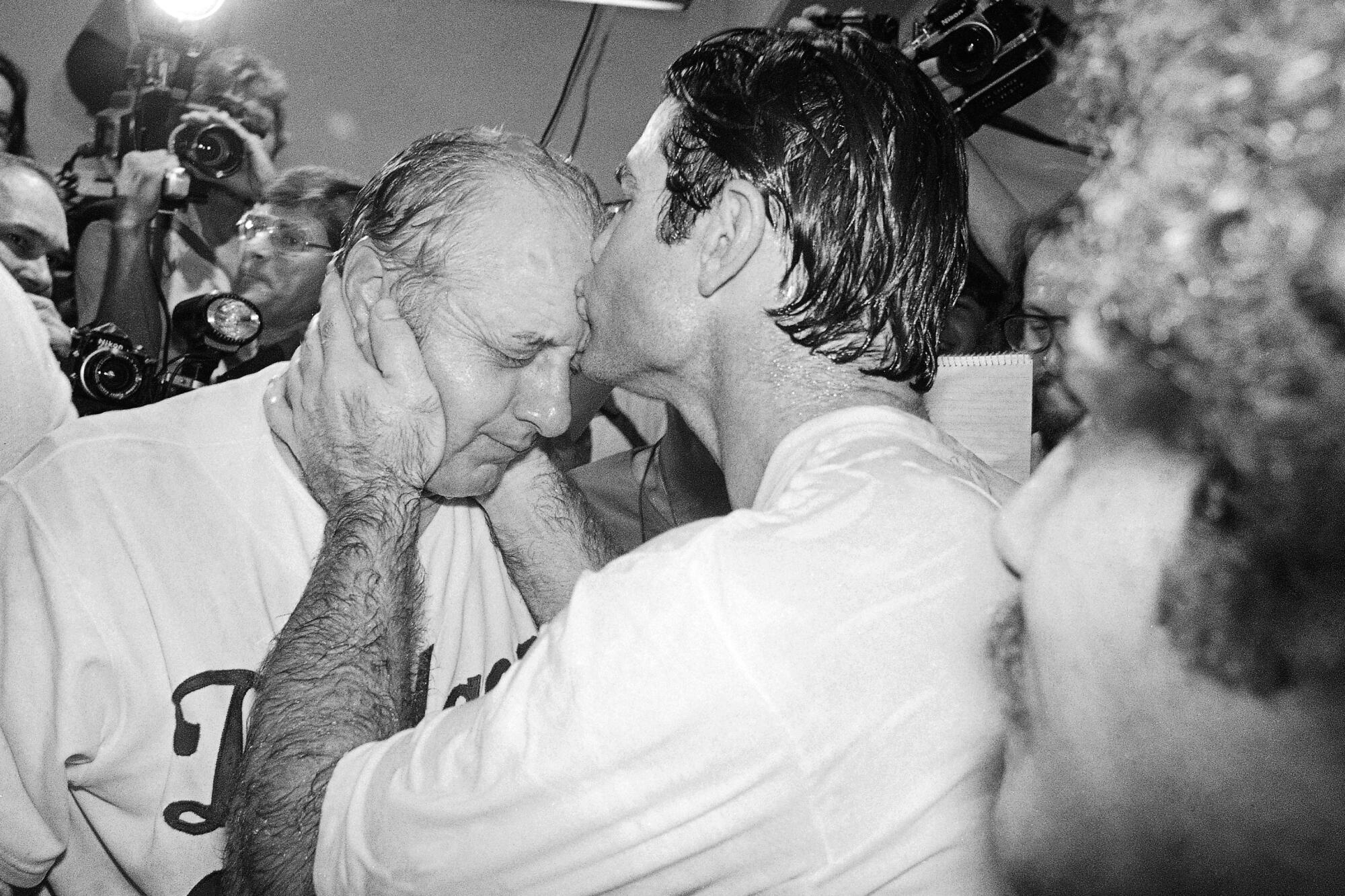

In Los Angeles, voters lit up as they posed for photos with the former all-star Dodgers first baseman who anchored the team’s legendary infield in the 1970s and early 1980s.

A few knew that Garvey, a Republican, was running for the U.S. Senate. But they all remembered his steely forearms — “Hey Popeye,” one yelled — and success on the diamond in two baseball-mad towns.

“Is he a Republican?” Kenneth Allen, 56, asked a reporter as Garvey toured the San Diego homeless shelter where Allen works. “I’m a Democrat but if he is the best person for the job, I’d think about it.”

Garvey’s baseball fame is central to a Senate campaign that, at best, is considered a long shot in a state where GOP candidates running statewide often receive an icy reception from California’s left-leaning electorate. He hopes what propels him into contention is a nostalgia for his playing days and a political message light on specifics but heavy with criticism about the declining quality of life in California and the scourge of illegal drugs flowing through cities.

This excitement from older fans trailed the 75-year-old first-time politician as he moved through Southern California last week on a listening tour about homelessness. Last fall, he joined a Senate race already dominated by prominent Democratic members of Congress: Adam B. Schiff of Burbank, Katie Porter of Irvine and Barbara Lee of Oakland.

“Once we get through the primary, I’ll start a deeper dive into the [issues],” Garvey said Thursday outside the San Diego homeless shelter.

“I haven’t been at this very long, so you got to give me a little bit of leeway here. But that doesn’t mean that we’re not full-speed ahead in policy and coming up with ideas that will make a difference.”

Since entering the contest Garvey has offered a range of views, including saying he supported closing the U.S.-Mexico border, but also taking decidedly more liberal positions on subjects such as gay marriage and abortion rights — both of which he supports.

“The people of California have spoken. They have spoken for abortion, and as an elected official my responsibility would be to uphold the voice of the people and I pledge to do that,” Garvey told The Times on Thursday in Compton during one leg of his listening tour.

Since entering the race, Garvey quickly rose to be the field’s top Republican, increasing his chances of finishing in the top two of March’s primary election and advancing to the November general election. In the latest UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies poll, which was co-sponsored by The Times, Garvey finished in third with support from 13% of likely voters. He trailed behind Porter and Schiff, who had 17% and 21% support, respectively.

Support for Garvey has nearly doubled since August, evidence that he might have enough momentum to consolidate the Republican vote and attract some No Party Preference voters for a strong showing in the March 5 primary.

It’s why, in part, Porter and Schiff have ramped up criticism of Garvey’s party affiliation and support of former President Trump. The first Senate race debate is this month and the Democrats on stage are expected to go after the late-entering Republican candidate.

“With Trump’s MAGA loyalists turning out to vote for him in the presidential primary the same day as our election, it could give Garvey the boost he needs,” one recent Schiff fundraising email said.

Garvey told The Times he voted for Trump twice, reasoning that he was the best choice on the ballot in 2016 and 2020. There were good things Trump did, he said, but he won’t identify them. He previously said he doesn’t have an opinion on who is responsible for the violent pro-Trump insurrection at the U.S. Capitol three years ago.

For Garvey to do well in the March primary, he needs the support of California Republicans loyal to the former president. But in doing so, he runs the risk of angering an even larger proportion of the electorate who despise Trump.

On Thursday he sidestepped the question of whether he’d vote for Trump this fall or accept his endorsement, saying with a smile: “That’s a hypothetical question. If he calls, I’ll let you know.”

“I’m a moderate conservative,” he said. “I never took the field for Democrats or Republicans or independents. I took the field for all the fans and I’m running for all the people, and my opponents can’t say that.”

Stanford University public policy lecturer Lanhee Chen, a Republican who ran unsuccessfully for controller in 2022, said that Garvey starts with an advantage many Republican candidates lack: People know Garvey and have fond memories of him. If he were to make the runoff, which Chen says is possible, he’ll face the monumental challenge of overcoming Democrats’ enormous voter registration advantage.

Garvey, a former All-Star first baseman for the Dodgers, may upend the race to fill the U.S. Senate seat held by the late Dianne Feinstein since 1992.

In the general election, Garvey, who said he wants to serve just one term, would hope to consolidate his hold on Republicans and pick off a small margin of Democrats and No Party Preference voters by appealing to moderates — and in particular, Latino voters — who might be attracted to his Catholic faith and focus on economic issues.

Chen said in a general election he would need to face head-on some of the questions about Trump. The recent Berkeley poll indicated that 34% of likely voters have a favorable view of Trump, compared with 63% who have an unfavorable view, and of that, 58% have a strongly unfavorable view of the Republican presidential front-runner.

“Every Republican candidate, regardless of where they sit on the spectrum of these questions, is having to address them, which is part of the reason why Trump is such a unique challenge for the Republican Party in a place like California,” Chen said.

Democratic political consultant Bill Carrick says that Garvey’s rise is a reflection of the weak Republican bench of candidates. The state has a long history of these sorts of candidates, he said — pointing to Hollywood action star Arnold Schwarzenegger’s election as California governor in 2003, when Democratic Gov. Gray Davis was recalled from office.

In that election, Carrick said that voters in Los Angeles in particular didn’t just see Schwarzenegger as a film star. They saw someone who had been doing charity work in the community and was known to voters on a very human level.

Garvey, who lives in the Coachella Valley, has flirted with politics for decades after his successful baseball career, which included a World Series title and 10 National League all-star selections that ended in the late 1980s.

“The Republicans have no farm system now, so nobody moves up the ladder,” Carrick said, pointing to the small Republican minorities in the state Legislature.

“That leaves it open for people, like Garvey, who have their own capacity to jump in.”

Still, a general election in which 47% of the electorate are registered Democrats, 24% are Republicans and 22% are No Party Preference will be an uphill battle, Carrick said.

During his campaign swing last week, Garvey toured a shelter in downtown San Diego before visiting Los Angeles’ Skid Row alongside the head of the Downtown Industrial Business Improvement District Estela Lopez and a local business owner named Sergio Moreno. He took photos with five uniformed Los Angeles police officers and told them, when elected, he’d make sure that people “you arrested weren’t back on the streets before you finished the paperwork.”

After explaining the challenges of owning property in the vicinity of Skid Row, Moreno told Garvey about the joy he experienced getting a ball signed by him at an event at the Glendale Galleria’s JCPenney in the mid-1970s.

Garvey heard a similar message when he arrived at his final stop of the tour — Ruben’s Bakery and Mexican Food in Compton.

The business’ interior was essentially destroyed after a crowd of more than 100 people robbed the bakery during an illegal street takeover this month.

But Thursday the 48-year-old establishment was back open and Ruben Ramirez Sr., 83, and his wife, Alicia, 76, were behind the counter in Dodgers gear.

Both recalled watching games as a family and the joy Garvey brought their family — including Ruben Ramirez Jr., who now runs the store.

“All my life I wanted to meet him,” Alicia said in Spanish — a Dodgers scarf around her neck. “He’s such a handsome man.”

She clutched a ball he signed for her and snapped a photo to send to her family. Ramirez Jr. said their family wasn’t political and just works hard. They had little interest in talking politics, he said.

Garvey didn’t either. He just smiled and shook their hands.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.