On New Year’s Eve in 2020, Tom Girardi called me from his cellphone.

In a brief voicemail left in The Times’ general mailbox, the once fearsome attorney said there were “slanderous statements” in an article I had co-written.

A lawsuit, he said, was coming soon.

At another moment, a voicemail like that from Girardi might have elicited caution, even alarm.

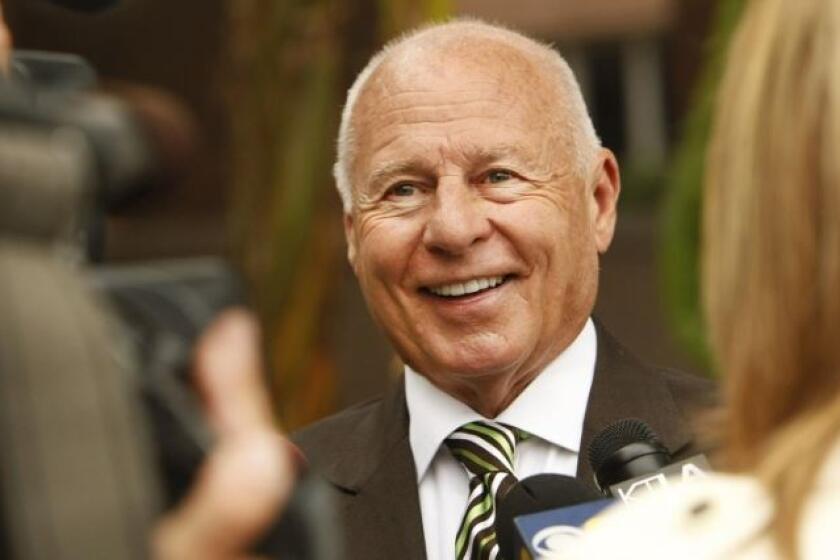

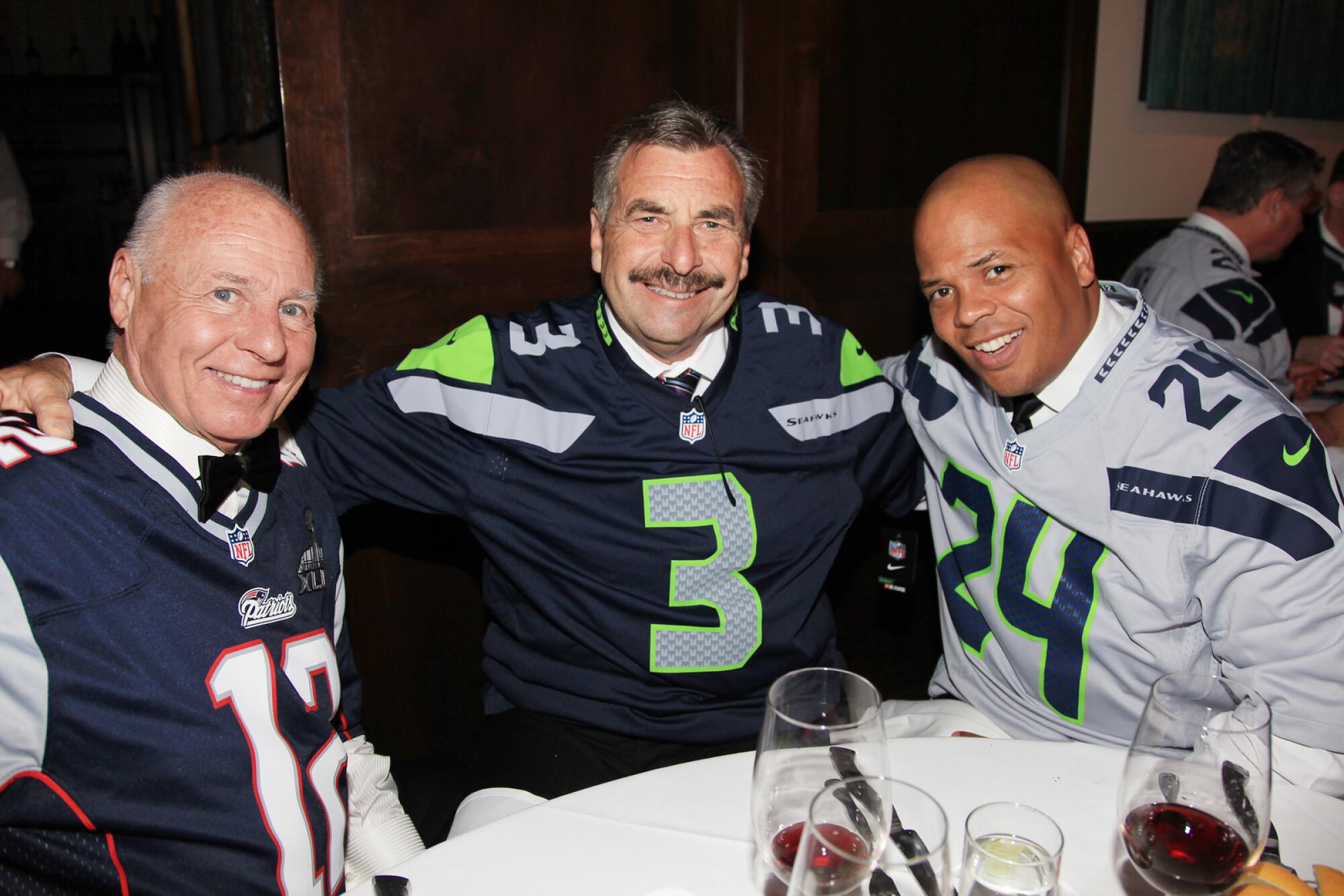

After all, for much of his career, Girardi was a formidable lawyer whose calling card was the “Erin Brockovich” case. He had won millions for scores of clients, and was on a first-name basis with judges, governors, senators. He was the type of opponent who knew his way around the corridors of power and how to leverage that for maximum gain.

But all of that had changed a few weeks before.

A federal judge in Chicago had determined that Girardi misappropriated more than $2 million from clients — widows and orphans whose loved ones died in a Boeing plane crash in Indonesia. Boeing had wired the money to Girardi’s firm, yet it never reached his clients.

Appearing by phone in that hearing, Girardi said nothing as the judge berated his lack of ethics and “unconscionable” theft of client money. Girardi’s lawyer at the time suggested that the then-81-year-old was mentally incompetent.

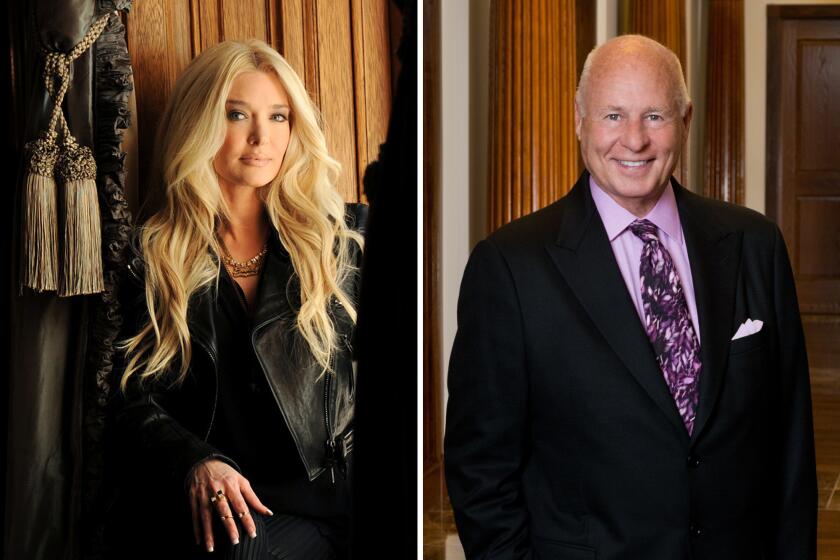

Unswayed, the judge froze Girardi’s assets and referred him for criminal investigation. His wife, Erika Girardi, one of the stars of “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills,” had already moved out and filed for divorce. Within days of the judge’s ruling, creditors moved to force Girardi and his nearly defunct law firm into bankruptcy.

I had chronicled Girardi’s rapid fall from grace with my colleague Harriet Ryan, including in a front-page story detailing his epic rise, legal wins, profligate spending — mansions, cars, clothes and two private jets — and swift unraveling.

Tom Girardi is facing the collapse of everything he holds dear: his law firm, marriage to Erika Girardi, and reputation as a champion for the downtrodden.

We could not get Girardi, or his lawyers, to return numerous calls and emails before publishing our stories. So it was a bit of a shock that he suddenly wanted to talk.

What did he want? Was he truly incompetent, as his defense lawyer had indicated? Didn’t he have more pressing matters to worry about — like paying his clients or the looming criminal probe?

He called twice that New Year’s Eve, again on New Year’s Day, then the day after that, in a pattern that would soon become a kind of post-publication ritual as Ryan and I continued to investigate his misdeeds.

I didn’t learn of Girardi’s messages until Jan. 5. That day, I phoned him and took notes.

“You hurt us so bad with that article,” Girardi told me as I typed. “I wanted to let you know that everything was cleared up and things are good.”

It was stunning to hear his voice — as smooth as I remembered from our brief interactions over the years but frayed by age, even wobbly. I took in what he said and pressed him on what, exactly, was “cleared up.” His firm was in a forced bankruptcy; there was no way any widows and orphans had just received millions owed to them.

“All been distributed,” he insisted. “Those checks went out two days ago for the final amount.”

Did the plaintiffs know that?

“I don’t know,” he replied. He alluded to unspecified health problems in recent weeks, and said of our coverage, “You hurt me so bad, kind of a one-sided thing.”

“Mr. Hamilton, it was really crappy of you,” he continued. “It really hurt me. People left the firm because of the article. ... It was really hard on me. I didn’t think it was fair.”

“I’ve been a pal of that newspaper for 100 years,” he added.

I had entered an alternate universe, one where Tom Girardi was still running his eponymous law firm, he had money in the bank and his clients’ checks had been mailed two days prior. None of this was true, but it wasn’t clear whether he grasped that.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

When I patched Ryan into the call — a bid to include a witness — we told him that we had tried to speak with him and his attorneys before publishing. But shortly after Ryan joined, Girardi announced that he had another call coming in.

“They just handed me a note from the court regarding Chicago,” he said, and hung up.

For the next month, the calls stopped. During that time, Girardi’s brother Robert put him in a conservatorship, telling the court that the former legal titan had abysmal short-term memory and was “incapable” of understanding that he and his law firm were bankrupt. Robert Girardi said his brother “offers solutions and opinions that are factually impossible.”

In early February, the calls resumed — nearly all voicemails to the newspaper’s reader inbox, which receives complaints and comments about coverage. Girardi should have had my cellphone number from my call to him, but he continued dialing the general inbox, at times addressing me as “Chamberlain.”

“This is a final demand to retract the fraudulent story that Chamberlain wrote, that I was trying to get the money for my lifestyle,” he said on Feb. 7.

On March 3: “I’ve received many awards for my ethics. Maybe he would like to call me and make sure that we are on the same page.”

On March 6, 2021, Ryan and I published a detailed account of Girardi’s dealings with the State Bar of California, which regulates and disciplines attorneys. The report was long and unflattering, detailing the cozy relationship that Girardi had cultivated with those tasked with preventing and prosecuting the type of fraud he was accused of perpetrating with the orphans and widows from the Indonesian plane crash. It was based almost entirely on records we had culled from courts and public agencies.

Tom Girardi and his firm were sued more than a hundred times between the 1980s and last year, with at least half of those cases asserting misconduct in his law practice. Yet, Girardi’s record with the State Bar of California remained pristine.

In the 24 hours after publication, Girardi blitzed The Times with messages.

“This is Thomas Girardi. I’m the victim of your libel and slander that hit the press,” he said. “This is a [demand for an] immediate retraction of all the fraud. That has to be done Monday morning at 8:30, because the lawsuit will be filed Monday afternoon. What a bunch of miserable, rotten, despicable, lying — I will get even for the lies and the fraud.”

Multiple calls laced with anger, bluster and threats poured in March 7, sometimes within 30 to 45 minutes of the previous call.

“This is for Hamilton,” he said in one message. “I guarantee you, I’ll spend the rest of my life, if necessary, getting fairness. And maybe — doing some real good for me, and massacring you.”

“Oh, God, I have a lot to say,” he added. “You’ll see it in the complaint. And I don’t think the newspaper should defend you, because this is intentional acts.”

At The Times, the messages were logged and transcribed by editorial assistants and shared with our editors, Ryan and me. Girardi left at least 26 voicemails in March 2021, expressing varying degrees of rage. He was contesting the accuracy of the stories, he wanted the stories retracted, he promised to sue us personally, and he also, it seemed, just wanted to talk.

Taken together, the messages posed a difficult quandary about the primary subject of our articles.

The foundation of journalism is to talk to all sides, keep an open mind, ask questions and follow the evidence. Reporters are not here to broadcast their judgments or render a verdict but to deliver to accurate information, framed fairly and sourced honestly, so that readers can decide.

How could we accurately — and ethically — include Girardi’s perspective? Even more fundamentally, how could we make him aware of our reporting and give him a chance to respond?

His own lawyers were publicly stating his cognitive impairment. He was in a conservatorship. His brief interview with me not only contained standard denials of wrongdoing but was wholly divorced from reality. Was it fair to press him for a response, or did that veer on the exploitative?

We made the decision to go through Girardi’s representatives.

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

I informed his brother Robert’s attorney of the voicemails, hoping it would open the door to perhaps an interview with Girardi, Robert or another representative. Before publication of the March 2021 article, Ryan and I shared questions with his attorneys and his conservator’s attorneys.

It was clear that Girardi wanted to talk — he kept peppering The Times with demands for us to call him. But those around him repeatedly balked.

“As I wrote to you previously, the circumstances that gave rise to the conservatorship render an interview with Tom Girardi inappropriate. Your description of the voicemail you received confirms that reality,” said Nicholas van Brunt, the lawyer who initially handled the conservatorship for Girardi’s brother.

And so the calls continued through much of 2021 — sometimes multiple messages in one day.

Often, as in the brief interview with me, Girardi seemed confused or even unmoored from reality. In a few messages, he erroneously described the Indonesian plane crash case as one involving Irish clients and lawyers.

“These were wrongful death cases that happened in Chicago. All of the families were in Ireland. All of the deceased were Irish,” he said in one voicemail.

Clients who have accused Tom Girardi of misconduct will be tracking the new season of ‘Real Housewives,’ hoping for evidence to bolster their case.

He also invoked unnamed “judges” to fortify his threats — something we later learned was a long-running shtick.

“Several judges have contacted me, and they said this is so slanderous, something should be done to this guy Hamilton,” he asserted.

While Ryan had co-written and co-reported the stories, he fixated on me, describing me to my bosses as “the wonderful, lying, miserable, rotten, despicable employee of yours, Hamilton.”

I was less concerned about the string of ad hominem attacks than what the messages could mean.

What was going on in his head? Was this part of an elaborate ruse? An effort to bolster the case for his incompetency? Or was this simply a man in the twilight of his life with dementia and a cellphone, discovering newspaper articles about him as if for the first time?

Girardi has been represented by the federal public defender’s office since criminal charges were filed against him. Contacted Sunday, Deputy Federal Public Defender Charles Snyder said he and his colleagues could not “meaningfully comment” because they needed more time and either a full transcript or the audio of their client’s voicemails.

From the moment Girardi’s firm imploded, the question of whether he was exaggerating the extent of his mental deterioration had become a recurring topic among the state’s legal community and legions of “Housewives” viewers.

Associates of Girardi whispered about a long-running decline, referencing a car accident in 2017 that seemed to have been a turning point. Others noted his increasing agitation, his drinking and some erratic behavior.

In 2021, Robert Girardi’s lawyer filed in court a Long Beach psychiatrist’s diagnosis for Tom Girardi that said he had “Alzheimer’s disease with late onset,” citing memory loss, delusions and “severely disorganized thinking.”

Even prosecutors at the State Bar had suspicions, noting that the Alzheimer’s diagnosis came “only after [Girardi] became enmeshed in mounting legal troubles and as he is facing imminent State Bar discipline.”

Prosecutors’ skepticism fanned the flames of public doubt, and my own.

The voicemails, meanwhile, continued, like this one from July 2021: “My name is Tom Girardi, the guy that you defame all the time.”

By that point, more than a hundred creditors had lined up. Many alleged exactly what Girardi professed to abhor: that he had stolen their settlements and left a trail of excuses and lies to fend them off.

A Times investigation draws on newly revealed records about Tom Girardi’s legal practice, opening a window onto the secretive world of private judges.

In early 2023, Girardi was indicted in Los Angeles and Illinois on federal fraud charges, triggering a more fulsome — and public — examination of his cognition.

His defense lawyers sought to have him declared unfit for trial, kicking off a months-long process to assess his mental competency.

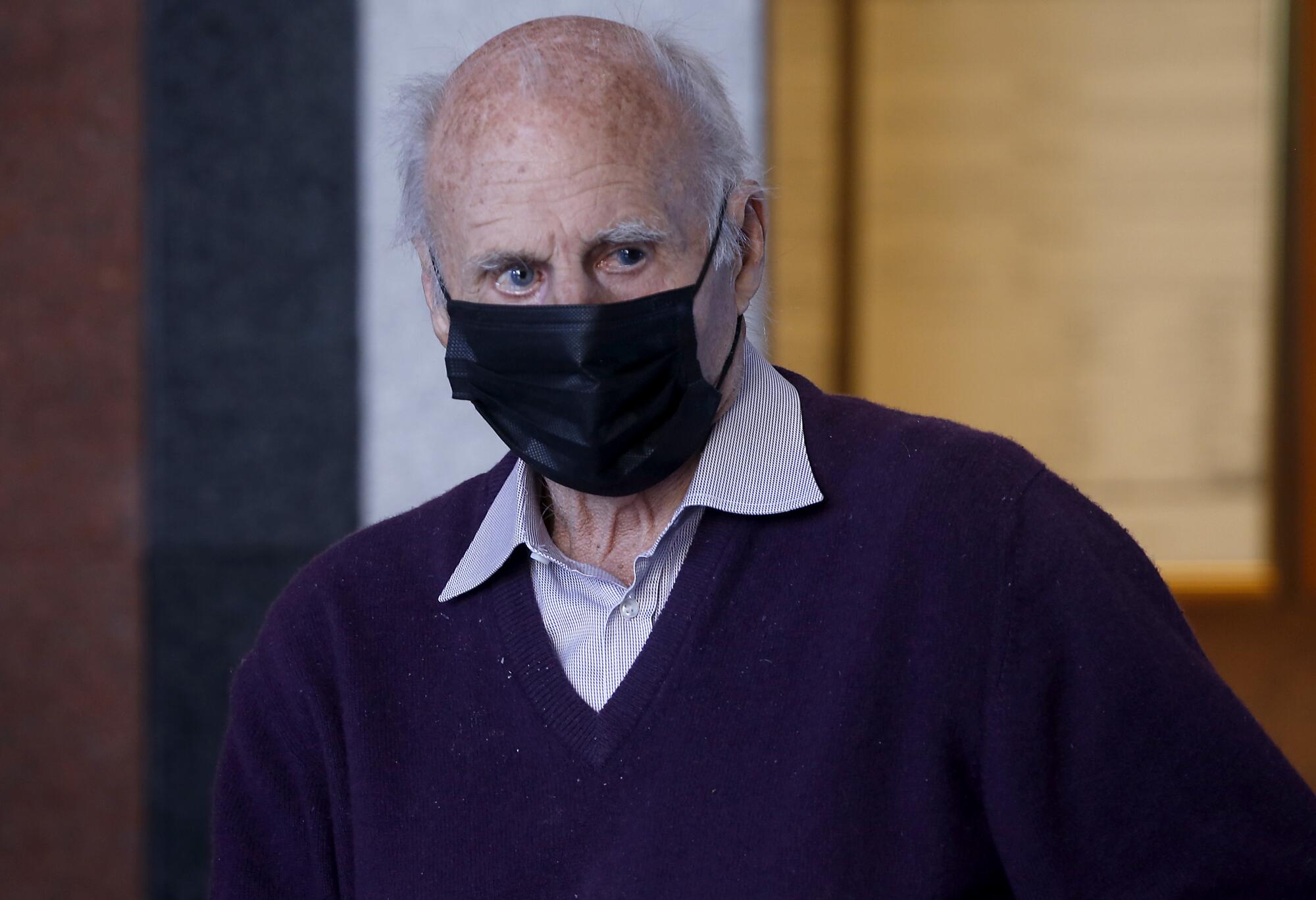

In a multiday hearing last summer, a parade of medical experts testified in downtown L.A. about the state of Girardi’s mind.

Girardi’s own experts said he had little short-term memory, could not care for himself, believed he was still a lawyer despite his disbarment, and thought he lived in his Pasadena home when he had for years been staying in assisted living facilities.

The government, meanwhile, offered experts who acknowledged Girardi had some cognitive impairment but insisted he was malingering, or feigning, the scope of his decline. They pointed to inconsistencies, such as his claim that he didn’t know his third wife, Erika Girardi, despite answering her phone call during one evaluation and remembering she was traveling to Spain that day.

Another government expert opined that his inability to remember was selective and beneficial to his case. The same expert pointed out that Girardi “began wearing the same burgundy sweater to all evaluations,” even “actively searching for the sweater in the dirty clothes if needed,” according to court records — a sign of a functioning memory.

Judge Josephine Staton ultimately sided with the prosecutors and agreed that Girardi was competent, issuing a ruling this Jan. 2 that although he had “mild-to-moderate” impairment, he was “exaggerating his symptoms and partially malingering.”

In her ruling, Staton also pointed to voicemails from Girardi in 2020 and 2021. It was clear, she said, that he understood he was being accused of fraud, including in his voicemails to fellow attorneys on the Indonesian case in which he offered to reach a settlement.

The judge also pointed to voicemails he left with former colleagues in 2021, “often suggesting they start a new practice together,” a move that “demonstrated that Defendant understood that [his law firm] Girardi Keese was no longer operating.”

Reading over the judge’s ruling, I reconsidered the voicemails he had left for me over the years and regretted that I hadn’t made them public earlier. They had once seemed partly the expression of an octogenarian’s cognitive decline. Now, they took on greater significance.

Girardi remains out of custody in an assisted living facility. His former chief financial officer, Chris Kamon, has meanwhile been held without bail for more than a year.

For both men, trial is scheduled for May.

Girardi has continued to call the paper — hundreds of times in 2022, and eight times in 2023.

Around Jan. 26, 2022, he left a particularly memorable string of messages.

Around that time, the State Bar had disclosed that it was investigating whether insiders at the agency had helped Girardi elude discipline — an inquiry that we promptly covered in the newspaper. In the 48 hours after that revelation, Girardi left more than a dozen voicemails at The Times. He labeled an unspecified article “felonious” and said Ryan and I were “disgusting.”

“You’re miserable and rotten,” he said, “and I think a jury is going to agree with me.”

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.