- Share via

Not much happens on Kingswood Road without the neighbors noticing.

The one-block street in Sherman Oaks ends in a cul-de-sac, and the people who live in the multimillion-dollar homes along it know each others’ dogs, vehicles and daily routines.

So when they didn’t see Charles Wilding Jr., a shy, single man, for several months in the fall of 2020, neighbors became concerned. And those worries only intensified when a bubbly, young redhead named Caroline Herrling installed herself in Wilding’s house in the 3800 block and began a remodel.

“It was very rare to see anybody at the house,” said Roger Stanard, who has lived next door to Wilding since 2008. “I didn’t know what to make of her.”

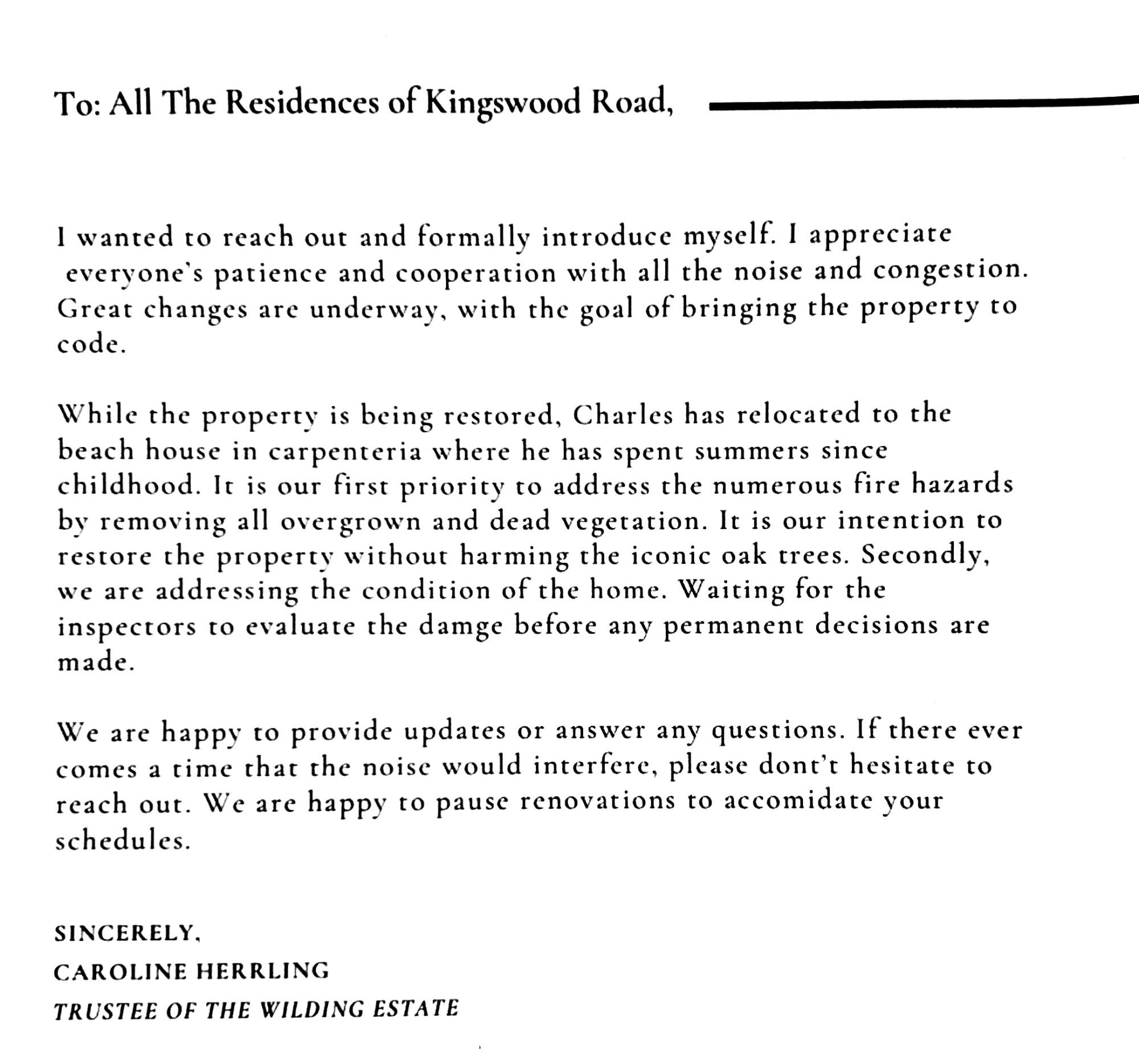

The gossip along the street grew so intense that Herrling circulated a letter reassuring everyone that Wilding was fine. She identified herself as the trustee of the estate and said, “great changes are underway, with the goal of bringing the property to code.

“While the property is being restored, Charles has relocated to the beach house in carpenteria where he has spent summers since childhood,” Herrling wrote.

But as the residents of Kingswood Road would eventually discover, none of that was true.

For one thing, Wilding was dead.

::

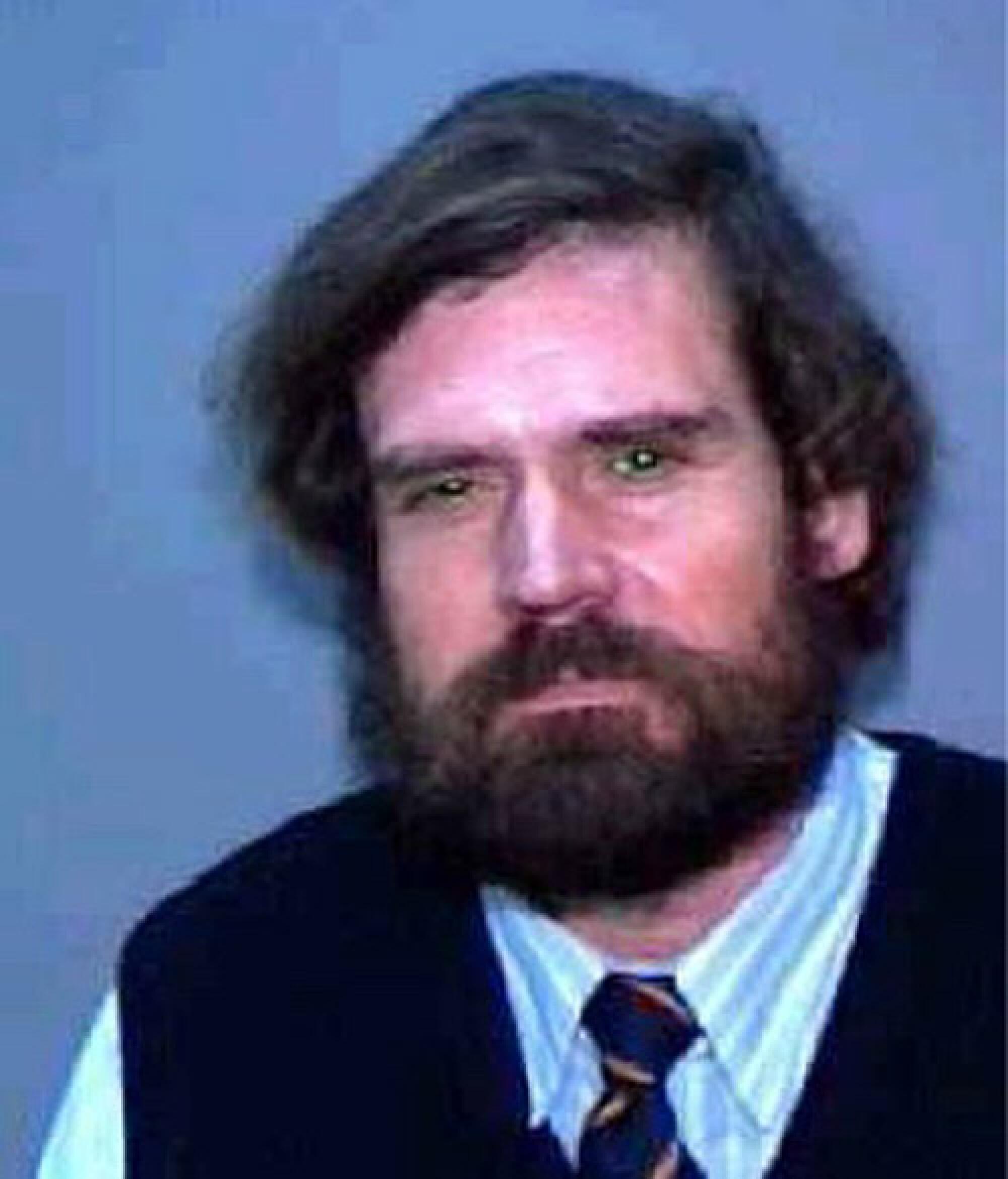

Wilding had lived in the two-bedroom brick home on Kingswood since he was born in 1951. Neighbors recalled him playing with kids along the oak-tree-lined street. A shy boy, they said, he’d avert his brown eyes when someone greeted him.

His father died when he was a teenager. As decades passed, he continued living with his mother, June Wilding, the two a familiar sight as they headed to the grocery store in their Cadillac on Saturday mornings. Neighbors described Wilding as a “recluse” and a “hermit.”

After his mother’s death in 2017, Wilding became even more withdrawn. Neighbors rarely saw visitors at the house or Wilding outside. They occasionally watched the frail, elderly man walk to a nearby Whole Foods in his puffy jacket and knit cap, which he wore even in summertime.

When neighbors offered him rides to the store, Wilding declined. When one resident offered to lend him electrical tools after an oak branch fell on his property, he said he didn’t need help. When he fell on his driveway and the man across the street rushed over, Wilding politely asked to be left alone.

“It’s hard to get to know a guy like that very well,” said Stanard, whose bedroom window looked down onto Wilding’s driveway.

In the throes of the pandemic, Wilding put up signs around his home saying he had COVID and not to come near. Then, he disappeared completely.

Suddenly Herrling was there, telling neighbors she had met the Wilding family when she and June were docents at the J. Paul Getty Museum. Herrling put dumpsters out on the street and started filling them with everything in Wilding’s home, including kayaks and art projects, one neighbor recalled.

Caroline Herrling pleaded guilty last year to conspiracy to commit wire fraud. Among her victims was Robert Tascon.

Then, a few days before Christmas 2020, a neighbor called police to report that she hadn’t seen Wilding in three months.

When officers responded to Wilding’s home for a welfare check on Dec. 22, Herrling met them in the driveway. She told them she was the trustee for Wilding’s estate, according to a police report. The house was in disarray and had black mold, she told the officers, and she was working to get it back in order. Herrling said Wilding was staying with friends. She couldn’t provide a current address, only a landline number she said was forwarded to his cellphone.

The cops tried the number. No answer.

The officers searched the home, but couldn’t find Wilding, according to the report. They talked to the neighbors, who expressed their concerns.

Herrling gave officers a case number for Adult Protective Services. A caseworker confirmed to police that they were looking into Wilding’s whereabouts but hadn’t made contact with him. The caseworker would later tell police she spoke with someone that same day whom she understood to be Wilding. He repeated Herrling’s line that he was staying in Carpinteria.

Adult Protective Services closed their case on Wilding on Jan. 8, 2021.

::

Nine months later, an anonymous call came in to Mark O’Donnell, a homicide detective supervisor with the LAPD.

The caller told O’Donnell that a man named Charles Wilding was possibly dead, O’Donnell recounted in an affidavit filed in court. His death, the woman said, was not being reported because people were using his identity for financial gain.

The individuals responsible were drug users and dangerous people, the caller said, before providing Wilding’s address. She hinted that Wilding’s death may have been due to foul play. Then she hung up.

O’Donnell had 13 years of experience as a homicide investigator and was no stranger to the bizarre. But nothing, however, was quite like this.

He called Herrling that same day, according to court filings. She gave him a fake number for Wilding. When he called back, he told Herrling to provide a good phone number and address for Wilding by the following day or he’d open a missing persons investigation.

The next day, Herrling called, said she was with Wilding and put him on the line, O’Donnell wrote. The man gave his phone number and an address where he was staying in Simi Valley. O’Donnell asked the man on the line if he knew his Social Security number or his driver’s license number. He didn’t know either.

Within days, O’Donnell visited the address “Wilding” had given him. The man who answered the door said he knew Wilding vaguely but had not seen him in years.

So he went to Herrling’s pricey apartment on Beverly Glen Boulevard. Herrling told O’Donnell that Charles’ mother, June, had named her as a secondary trustee to her son. She claimed Wilding couldn’t carry out the responsibilities of trustee so they fell to her.

“If you have any life experience, and you talk to Carrie, you immediately pick up on her inauthenticity,” O’Donnell told The Times. “I think she tries too hard to be convincing.”

O’Donnell asked for a copy of the trust documents. He saw a receipt on the table for a phone she’d purchased with the number she later gave to police as Wilding’s.

When the detective asked Herrling if he could interview her again that December, she directed him to her attorney, Alex Kessel, O’Donnell said in his affidavit. The lawyer told O’Donnell that Herrling had no further information on Wilding’s whereabouts.

The more he dug, the more lies O’Donnell found. Many of the court filings allegedly naming Herrling trustee and beneficiary of the Wilding Family Trust had been falsified or forged. She had allegedly found a will naming Wilding as beneficiary and granting him $1.7 million; it, too, was forged, O’Donnell said.

O’Donnell called Rodney Gould, the attorney who was representing Wilding on the will Herrling had allegedly found. Gould told O’Donnell that he’d only spoken with Wilding by phone and that Herrling said he was in a nursing home. As Gould dug into Herrling and her filings, he discovered forgeries and falsehoods that he shared with the detective.

“I’ve been doing this for years, and it certainly opened my eyes to how diabolical people can be,” Gould said. “It really did make me question everyone and everything.”

As O’Donnell kept digging, he became the point man for Kingswood Road residents. They detailed the unusual activity that had started at Wilding’s home in January 2021, including several people coming and going and multiple vehicles parked on the street at all hours. They provided him with the letter that Herrling had distributed. One turned over license plate numbers he’d jotted down of seedy-looking people who went in and out of the home.

In June 2022, O’Donnell pulled Lyndon Versoza, a postal inspector and an expert in money laundering, onto the case. O’Donnell wanted Versoza’s help looking into the fraud aspect.

“My first step was to look at the bank records,” Versoza said. “It’s the old adage, ‘Follow the money.’”

In searching Herrling’s bank records, Versoza found a wire transfer in September 2021 from the sale of an Encino home that belonged to a man named Robert Tascon. Using forged documents, Herrling had sold the house out from under Tascon for $1.5 million.

The following year, Tascon killed himself.

Herrling used money from the sale to help pay for a home in West Hills. She turned the home into a sober living facility, and she and her boyfriend lived above the garage. The couple later told authorities they only smoked meth out of sight of the addicts they rented rooms to.

As the investigators dug, they continued untangling a criminal web featuring Herrling at the center.

::

Everything about Herrling was a facade, down to the hair she dyed bright red.

She had built a life far from her home state of Wisconsin. She told friends she did varying jobs, managing properties and working for a film director.

Dusty Bowman, who said she was friends with Herrling for nearly 20 years, described her as someone who “knew a lot of things about different subjects.”

“She seemed very grounded for someone living in Hollywood,” 45-year-old Bowman said. “It seemed like she had her s— together.”

Herrling, who said in court documents that she rendered “crisis management and litigation support services,” offered to help Bowman navigate her divorce. Bowman said Herrling later slapped her with a bill for around $100,000, then sued her for nonpayment.

Their friendship devolved into a legal battle. Bowman reported Herrling to the state bar for unauthorized practice of law. Herrling later applied for restraining orders against Bowman. Bowman said it cost her $13,000 to defend herself and that the restraining orders were eventually dropped.

“I thought that she was a very interesting person, I thought that she was fun,” Bowman said. “I didn’t see that she was dangerous.”

In January 2023, investigators obtained a federal warrant to search Herrling’s apartment — which she had been locked out of for not paying rent — and her West Hills home.

They found fake and stolen driver’s licenses and identification cards, credit cards, Social Security cards, birth certificates and passports that weren’t in Herrling’s name, O’Donnell said in his affidavit. They also found pieces of paper on which someone had practiced June Wilding’s signature.

They found psilocybin mushrooms, heroin and methamphetamine. Investigators also recovered 16 guns, including assault rifles, handguns and un-serialized “ghost” guns, according to the affidavit. Many of the guns were loaded, including one in Herrling’s purse. Zip-tied to the closet door were AR-15 guns, receivers, a shotgun and magazines.

Authorities found fake badges for the Drug Enforcement Administration and the Diplomatic Security Service. There was also a badge for a Beverly Hills Police Detective. Herrling told authorities she used the badges as “costume.”

On Herrling’s phone, Versoza wrote in a court filing, he saw screen captures of Google satellite views of affluent areas, which had homes with algae-filled swimming pools marked by pins.

“This identified valuable real estate that had fallen into disuse and may not have been occupied, and therefore was vulnerable to a takeover of the kind she did with Charles Wilding’s property,” he wrote.

Law enforcement agents also found digital spreadsheets that contained tabs with titles such as “Heir Index,” “Heirs Name,” and “Current Balance,” as well as tabs containing property ID numbers. Searches of Herrling’s digital devices revealed online searches for “millionaire” and “Obituary.”

The same day they executed the search warrant, O’Donnell and Versoza arrested Herrling for wire fraud conspiracy, aggravated identity theft and possession with intent to distribute controlled substances.

::

Within days, investigators arrested Matthew Jason Kroth, a suspected co-conspirator of Herrling. When they searched his truck, they found documents related to June and Charles Wilding.

Kroth told O’Donnell and Versoza that he was an “urban explorer,” which he said meant he targeted and burglarized homes in affluent neighborhoods, according to a criminal complaint. He said he had broken into Wilding’s home and found his body decomposing.

He told investigators he stole jewelry and other valuables from Wilding’s home, according to the complaint. He also said he and others jointly looted the estate and bank accounts tied to Wilding. Kroth said he made off with $140,000.

Herrling pleaded guilty in March 2023 to one count of conspiracy to commit wire fraud. Officials with the U.S. Justice Department said she was part of a nearly $3.9-million scheme.

Kroth pleaded guilty in October to conspiracy to commit wire fraud and possession with intent to distribute methamphetamine.

In a sentencing memo filed in January, Assistant U.S. Atty. Andrew Brown laid out the grisly events that followed Wilding’s death. He wrote that Herrling and co-conspirators removed Wilding’s body from his home and attempted to dissolve it in acid and lye on the rooftop balcony of her apartment. They let it sit for a week, investigators said, occasionally stirring the liquid with a wooden baseball bat.

When that didn’t work, Herrling and her co-conspirators dismembered the body, placed the pieces in vacuum-sealed bags and transported them to the Bay Area, according to the Department of Justice. Brown wrote that Herrling crushed Wilding’s teeth and bones “to make it harder to identify his remains.”

“[Herrling’s] co-conspirators, some of whom had been to prison repeatedly, did not help [Herrling] hack apart Mr. Wilding’s body, a fact she often reminded them of to justify keeping the lion’s share of the fraud proceeds for herself,” Brown wrote. He noted that Herrling purchased corpse smell deodorizer, a cadaver bag, gloves and toxic chemicals in hopes of liquefying Wilding’s body.

Brown wrote that Herrling then turned the trip to the San Francisco Bay “into a mini-vacation,” renting a muscle car for the drive, posing for photographs on the sailboat used to dump Wilding’s remains and returning to L.A. by private jet.

“It takes an exceptionally ruthless person to turn the disposal of a victim of identity theft into a celebration,” Brown wrote.

Wilding’s remains have never been found.

“If not for [Herrling’s] obstructive conduct, an autopsy could have revealed whether Wilding was murdered or died of natural causes,” Brown wrote. “A forensic examination of his purported death scene might also have done so. But [Herrling] made that impossible when she spared no effort in eradicating Charles Wilding and any evidence of his death, removing even the floorboards of his bedroom where he likely died.”

The Wilding home was sold by June’s nephew — who was appointed by the court to administer her estate — for a little under $2 million last year. No one has yet moved in. It’s a case that’s rattled the residents of Kingswood Road.

“This is a street of people that pays attention,” said one neighbor. “If this is what can happen in a neighborhood where people are actually looking out for somebody like him ... it’s wild.”

::

Last Friday, during her sentencing hearing, Herrling sat in the federal courthouse in a tan prison uniform, with her legs shackled. Her hair, now brownish blonde, fell in curls past her shoulders.

The 44-year-old had gained weight since her arrest and forced abstinence from drugs. She gripped black glasses — which were missing a stem — to keep them from falling off her face as she reviewed documents.

Across the table from her were the men who had helped bring her down: O’Donnell, Versoza and Brown.

During the hearing, Herrling’s attorney, Kessel, asked Judge Maame Ewusi-Mensah Frimpong for leniency for his client. Kessel argued that Herrling did not have a prior criminal history, apart from a charge for trespassing, and that she was not a leader or organizer of the scheme.

“I know this issue of a decedent, Mr. Wilding’s body, is relevant and at least is involved in a lot of the issues here, including an appropriate sentence, but there’s never been an allegation at all and no evidence to suggest that my client caused any death of Mr. Wilding,” Kessel told the judge.

Kessel did not respond to The Times’ requests for comment.

Unswayed by Kessel’s arguments, Frimpong sentenced Herrling to 20 years in federal prison.

“Charles Wilding was a man. He was a human being … his life had meaning and purpose,” Frimpong said. Herrling had treated him “like a cash register.”

Herrling will serve decades behind bars. But investigators say one question will likely always remain.

How did Charles Wilding die?

Times staff researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.