LAPD officer kept shooting after suspect was down, but court says law protects her

- Share via

Ruling on one of the most controversial and closely watched LAPD shootings in recent years, a federal appellate court said Thursday that the legal doctrine of qualified immunity protects officer Toni McBride from federal claims in the fatal 2020 shooting of Daniel Hernandez.

McBride is shielded by the law regardless of whether she used excessive force when shooting Hernandez six times, the last two when he was already badly wounded and on the ground, the court said.

“[A]lthough a reasonable jury could find that the force employed by McBride was excessive, she is nonetheless entitled to qualified immunity,” Judge Daniel P. Collins wrote for the unanimous three-judge panel of the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

McBride shot Hernandez after she and other officers arrived at a chaotic scene where Hernandez, on methamphetamine, had crashed his truck into multiple other vehicles and was brandishing a box cutter — which he refused to put down as he walked toward the officers, despite their commands for him to do so.

McBride fired in three volleys of two shots each — all in less than seven seconds. She fired the first volley as Hernandez advanced toward her, making him fall to the ground; the second as he got back to his hands and knees; and the third as he rolled on the ground.

McBride was cleared of any criminal wrongdoing, but the Hernandez family sued in civil court, seeking damages based on the claim that McBride’s actions had violated Hernandez’s rights.

After the U.S. Supreme Court ruling on modern gun laws, California cited precedents involving enslaved people and other minorities in defending background checks.

Collins, an appointee of then-President Trump, wrote that the family’s claims lacked a “pre-existing precedent” that made it clear that McBride’s actions violated established law. Without a previous case to reference “that squarely governs the factual scenario” of Hernandez’s shooting, Collins wrote, McBride could not be held liable.

The decision — in which Collins was joined by Judge Milan D. Smith Jr., a President George W. Bush appointee, and Judge Kenneth K. Lee, another Trump appointee — upheld an earlier dismissal of the federal claims by a lower court.

Separately, the appellate panel reversed the lower court on the question of whether Hernandez’s family has potentially viable claims of assault, wrongful death and civil rights violations under California law. The lower court had also rejected those claims, but the appellate panel found they could proceed because the final set of shots that McBride fired at Hernandez could be deemed excessive by a reasonable state jury.

“Because the reasonableness of McBride’s final volley of shots presented a question for a trier of fact, the district court erred in dismissing these state law claims based on its determination that McBride’s use of force was reasonable,” Collins wrote.

The ruling will result in a new state case in Los Angeles County Superior Court. In federal court, it further cements qualified immunity across the American West as a powerful shield for police officers who have been accused of excessive force — even when, like McBride, they have been found to have violated police department policies.

Narine Mkrtchyan, an attorney for Hernandez’s now 18-year-old daughter Melanie, said the ruling was a “half victory” for her client given that it preserved her state claims, but a “dangerous” precedent for future excessive force cases overall.

“The judges are really, really tightening on qualified immunity,” she said. “It’s very disheartening. I’m very concerned, seriously, about our civil rights.”

Arnoldo Casillas, an attorney for other Hernandez family members and Hernandez’s estate, said the ruling showed qualified immunity is a “sham for negligent cops,” but that he looks forward to pursuing justice for Hernandez’s family in state court.

McBride’s father, Jamie McBride, a prominent leader of the Los Angeles Police Protective League, the union that represents rank-and-file LAPD officers, said, “anybody with any type of police experience” knows that his daughter’s shooting of Hernandez was completely justified.

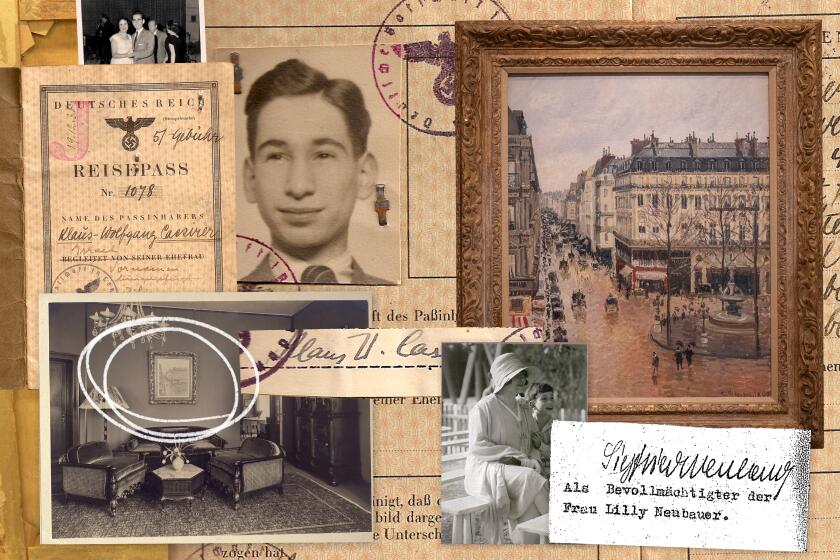

A Jewish family’s quest to reclaim a masterpiece painting stolen by the Nazis takes them across oceans and continents, into courts and back through time.

He praised her actions and rejected the finding of the Los Angeles Police Commission that she had violated department policy not with the first four shots, but with her final two. An independent forensic pathologist retained by Hernandez’s family theorized it was those last shots that killed Hernandez.

McBride noted that Hernandez was on drugs and had ignored police commands.

“You can’t fix stupid,” he said, of Hernandez’s actions.

McBride said his daughter would not be commenting on the latest court decision. The LAPD also declined to comment. Attorneys representing the younger McBride and the city did not respond to a request for comment.

McBride, a social media influencer and “Top Shot” police academy graduate who touts her prowess with firearms in online videos from shooting ranges, shot Hernandez on April 22, 2020 — about a month before George Floyd was killed by a Minneapolis police officer. The Hernandez shooting sparked protests in L.A. and became one of many cases cited by activists at the larger demonstrations in the months that followed.

The incident was captured by McBride’s body camera and by witnesses with smartphones.

Then-Chief Michel Moore defended McBride’s actions, but the civilian Police Commission ruled in December 2020 that her last two shots violated department policy. California Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta’s office later sided with Moore and cleared McBride of wrongdoing.

The appellate panel on Monday found that McBride’s first two volleys of shots were justified, but that the final two shots “present a much closer question” — and could be interpreted differently by reasonable jurors.

That wasn’t enough to clear McBride’s qualified immunity protections in federal court, the panel ruled, but was enough to justify another look in state court, where qualified immunity doesn’t apply.

Joanna Schwartz, a UCLA law professor, said it was “precisely the kind of case that should be decided by a jury,” given the dispute over the final shots.

Adam Vena’s claim that California took his child because he wouldn’t accept the child is transgender went viral. The case is far more complicated than that.

And yet, “what qualified immunity did in this case,” Schwartz said, was remove that decision from a federal jury, even “after the judges had concluded that a reasonable jury could have found that this conduct was unconstitutional.”

Schwartz said the decision was “emblematic” of two major problems with qualified immunity.

First is the idea that, to get around it, the Hernandez family would have had to put forward a previous case in which a court had ruled that another officer’s actions in a “virtually identical” set of circumstances were unconstitutional, Schwartz said.

“Those prior cases are hard to find simply because the same things don’t happen in precisely the same ways,” Schwartz said.

Second is the notion that such a prior decision would have served as a warning for McBride and other officers.

That is absurd, Schwartz said, because it “bears no relationship to how officers are actually trained.”

“They don’t read hundreds or thousands of cases and then recall the facts and holdings of those cases while they are doing their jobs,” she said. “Officers are trained about the general contours of the law — like the notion that you are not supposed to use deadly force against a person who is not a threat.”

It is that concept that McBride’s actions should be judged against, Schwartz said, not the “illogical” construct of qualified immunity.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.