Four brothers gathered in silence in the Los Angeles courtroom to hear the jury’s verdict. The decision came after 20 years of legal maneuvering by the brothers — bitter decades filled with accusations of fraud, intimidation and betrayal.

At issue was whether two of the brothers had struck an oral agreement nearly 30 years ago. Such a contract would determine ownership of vast real estate holdings worth billions, one of the highest stakes ever seen in a Los Angeles civil courtroom. One brother swore the contract existed; another denied it ever happened.

What might have been an uplifting story of an immigrant who soared to the pinnacle of American wealth had devolved into a saga embroiling not just the siblings but their mother as well.

And now, in Los Angeles County Superior Court, jurors filed into the courtroom where they had heard the story of a young man who had left his family in India and improbably had made, and possibly lost, a fortune.

It had all started with an opalescent rock.

Shashikant Jogani had a $250 moonstone to sell.

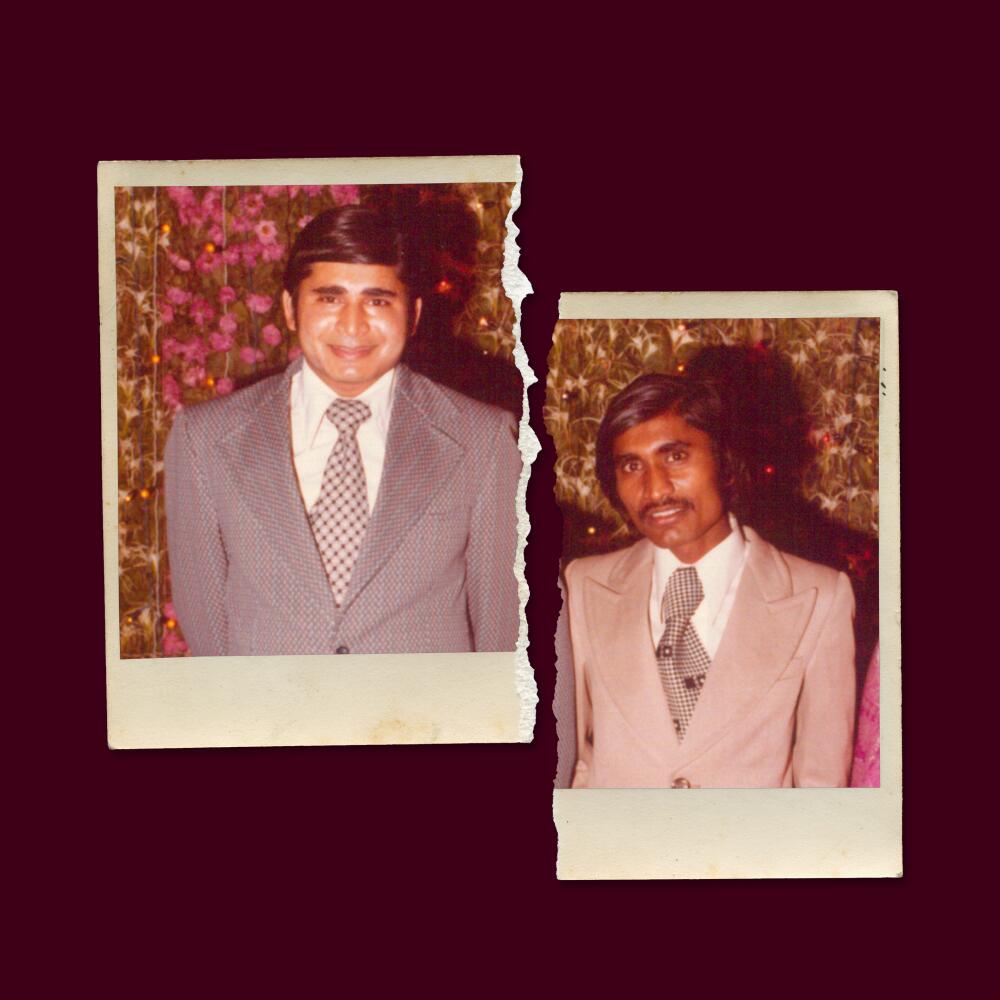

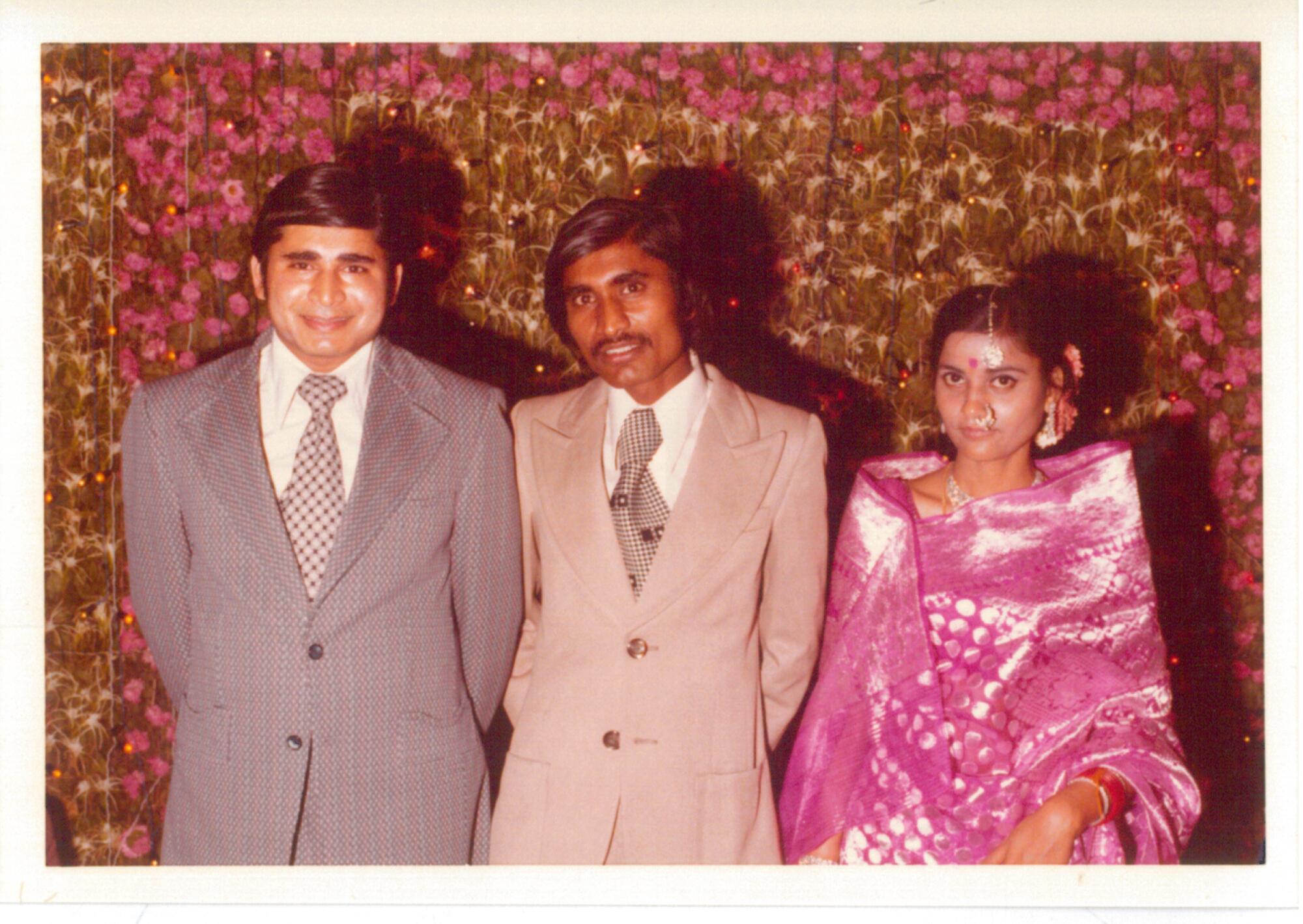

Shashi, as he is known, was attending USC in the early 1970s, the only member of his family to immigrate to the United States from their hometown in the Gujarat state of India. His story and that of his family was recounted in interviews with Shashi, other family members and tens of thousands of pages of court documents.

The firstborn of five sons and three daughters, Shashi was their father’s favorite, a model student who, according to family members, always got what he wanted.

Shashi worked night shifts at the Alexandria Hotel downtown, making $1.60 an hour, enough to buy him a pizza and Coke every day and cover his split of the $60 rent for an apartment he shared with a roommate. He was working to pay back his father and others for the tuition money he had been lent to attend school in Los Angeles.

But a friend in India had sent him a small treasure: the moonstone. Send me back $250 and keep the profit, the friend said. Shashi went to the California Jewelry Mart and sold the gem for $550.

He had no idea this little sale would be the first in a long career of flipping assets that would turn him into a megamillionaire diamond dealer and real estate baron.

While Shashi was making his way in Los Angeles, one of his younger brothers, Haresh Jogani, was learning the diamond trade in India. Unlike Shashi, Haresh struggled in school and dropped out at 14 to work in a diamond-processing factory near his family’s home in Palanpur. He worked 14- to 16-hour days — unpaid, in order to learn the craft — shaping diamonds on a lathe.

Haresh soon moved to the city of Surat to work in another diamond factory. He lived on the third floor of the factory, cutting 30 diamonds per day and sleeping on a bedsheet on the floor. He was still 14 when he began managing numerous employees in their 20s.

Haresh learned the trade quickly and at 15 decided to strike out on his own, descending into the hardscrabble diamond market on Dhanji Street in Mumbai in 1966. He bought and sold diamonds on the street, tucking cash into a secret pocket to keep his money safe.

Like his older brother, Haresh slowly developed his business into a behemoth and brought on the other three Jogani brothers, Rajesh, Shailesh and Chetan, according to the other brothers. He worked in Mumbai and Tel Aviv, dealing millions in diamonds.

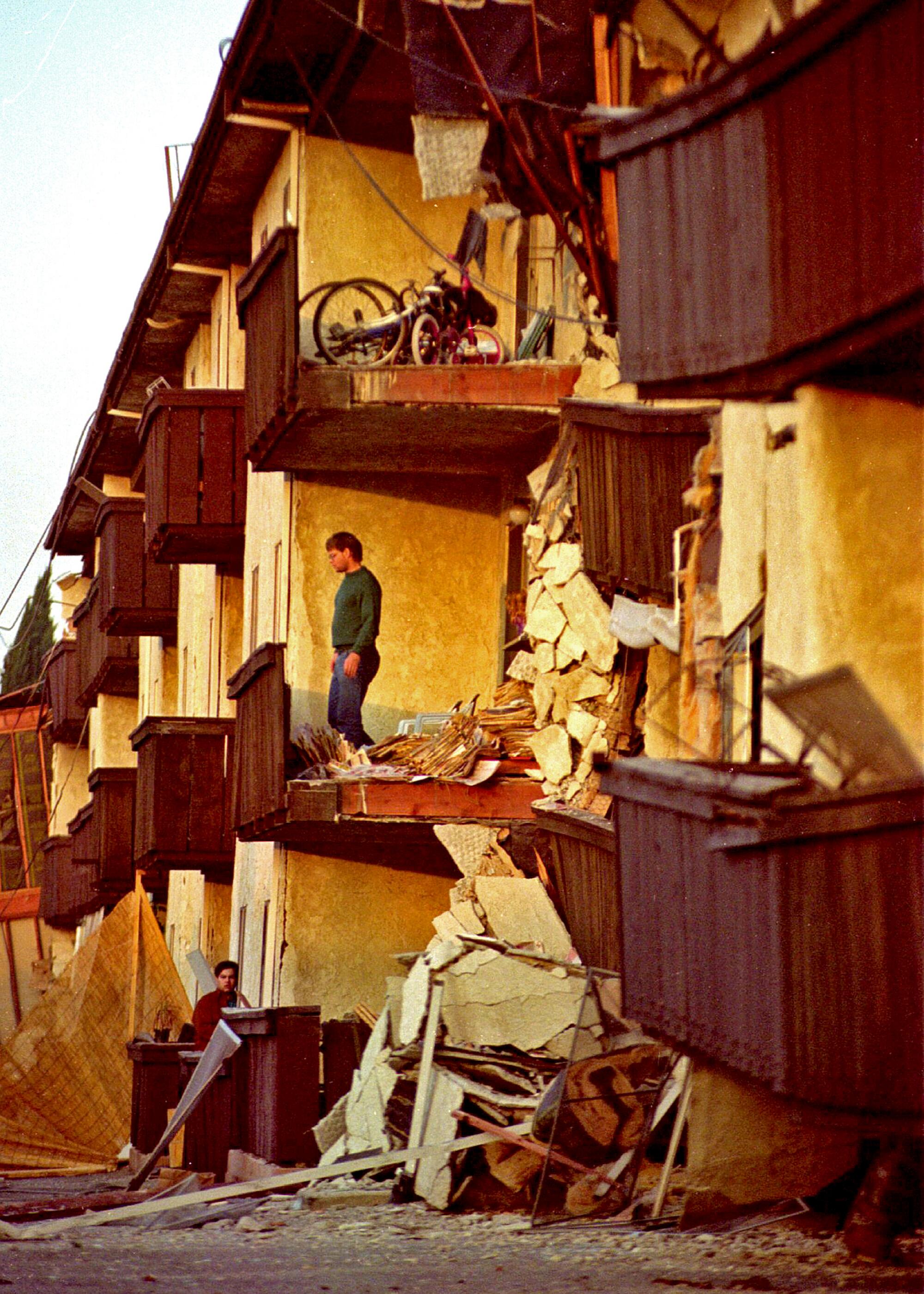

Shashi woke up with a start on Jan. 17, 1994, to the shaking of the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake.

Experts would later conclude that one of his properties, the 164-unit Northridge Meadows complex, was situated atop the epicenter. The first floor of the three-story building collapsed. Friends and family hurried to Northridge Meadows to check on their loved ones, including Jerry Green, who lived in a first-floor apartment.

“My husband was knocking at Jerry’s window on the first floor. My daughter said to him: ‘Dad, this is the second floor, not the first,’” Green’s sister, Sally Sawchuck told The Times days after the earthquake.

In total, 16 of Shashi’s tenants lost their lives.

He was sued by numerous tenants, but a state investigation and his insurance company found that he had not been negligent in his caretaking of the property. In mediation, his insurance company agreed to pay an undisclosed amount to victims’ families.

Shashi had been struggling even before the quake hit. With the end of the Cold War, the once-booming aerospace industry in Los Angeles constricted in the 1990s and renters were leaving the city. Vacancies rose and rents and property values fell. Shashi’s real estate holdings lost more than $100 million in value.

He defaulted on $53 million in mortgages on six different apartment complexes. Much of his portfolio was underwater.

Still, he believed that real estate was a good investment. Though prices were low, they would rise again. He wanted to fix up the buildings, put tenants in them and get back to making money.

But he needed capital to buy back the properties that were now in the possession of banks and trustees. Significant capital. Tens of millions of dollars.

Throughout late 1994 and early 1995, Shashi negotiated with a former competitor who offered to partner with him and give the cash infusion to revive his several companies. The deal was all but signed.

Shashi often discussed his struggles with Haresh, whom he described as the responsible brother who made big decisions for the family. Shashi told Haresh about the potential partnership. Haresh did not understand.

“Why you want to pay interest to somebody else? Why not with the family?” he asked Shashi, according to Shashi’s court testimony.

Here’s what Shashi said happened next.

“Haresh was proposing that all five brothers, including Haresh, would become partners. I will be 50% partner. Four other brothers are going to be 50% partner,” Shashi testified.

The four other brothers would bring the money and Shashi would do the work to rebuild the real estate empire.

As part of the deal, Shashi’s 50% stake in the companies would not be realized until he paid his brothers back for their initial investment plus interest, which at 12% was more than the potential partner had sought. That, Shashi testified, was his understanding.

Because Shashi was the only one with any California real estate knowledge — or United States residency — he was the one who was going to manage the portfolio, he added, even though Haresh and the other brothers would be the full owners until they were paid back.

Shashi and Haresh hammered out the details in person in Shashi’s Glendale townhouse in 1995, Shashi testified.

The deal was similar to the one Shashi had nearly struck, with one major difference: None of it was written down.

One of Shashi’s attorneys told him to get the deal in writing, but he never did. In Gujarati culture, he testified, deals are made on handshakes and oral agreements, especially within a family. Just like his brothers in their diamond business, according to the testimony of Rajesh and Chetan, business was based on trust.

And who could he trust more than family?

Besides, it was Haresh and the other brothers who were taking the risk by giving him more than $10 million, Shashi testified.

From the stand, he recalled telling his lawyer: “They are my brothers and I trust them.”

So he got to work.

One example: an 80-apartment complex in Panorama City he’d once purchased for $2.5 million before losing it in foreclosure. He bought it back at $1.1 million cash.

The apartments he bought were now owned by J.K. Properties, one of several new companies created under the brothers’ agreement, according to Shashi. Though all the brothers had a financial stake in the partnership, the companies were all under Haresh’s name.

Shashi had a simple outlook for making money. Buy a property at a low cost and increase the value with repairs or improvements. Then sell the property for a profit or refinance it at a more favorable interest rate.

Shashi said he eventually bought back dozens of apartment buildings, about 16,000 units. Over time, the portfolio grew to be worth about $1 billion, he testified.

All the work to rebuild was his alone, he testified.

“My brothers don’t know the business. They were in the diamond business. I was doing everything. Haresh was not staying here. The other brothers are overseas. Two brothers are in India. Haresh is in Israel. One brother is in Belgium,” Shashi testified.

In 1999, Shashi had a heart attack.

He realized after the health scare that he needed to pay back his brothers as quickly as possible so that he could begin to build up wealth for his wife and two children if he were to die.

Haresh and the other brothers had invested more than $43 million in the real estate business. In 1999, Shashi started small, paying back $1.5 million, he testified. The next year, Shashi paid back much more, bringing his debt to his brothers down to $14 million.

By late 2001, he testified, Shashi had paid off his debt to his brothers: $70 million, which included the interest.

He expected to be recognized as 50% owner in the companies. In the family’s small Beverly Boulevard offices, Shashi testified, he and Haresh had a confrontation.

He tried to start small, asking Haresh to split between the brothers $2 million that belonged to the companies. Based on the new breakdown of ownership, $1 million should go to Shashi and the other million would be split among the other four brothers.

Haresh refused, Shashi testified. Instead, Haresh offered a $1-million loan Shashi would have to pay back, he testified.

“I lost my mind. I said, ‘I made this empire,’” Shashi testified. “I really felt betrayed. ... I created this empire. I hired all the people. I hired the management company. I purchased all these properties. I refinanced.”

It was the “first time I felt that I should have everything done in writing, being educated in America, how big a mistake I made trusting my brother,” he said.

Rajesh flew to California and mediated the issue over the $2 million — Shashi got his half — but bigger questions remained.

Haresh refused to transfer the 50% stake to Shashi, according to Shashi’s testimony.

By 2003, Shashi decided he had to file a lawsuit — not just against Haresh, but against Rajesh, Shailesh and Chetan as well.

There was a problem. How could he prove the existence of a contract that was never written down when everyone else denied it ever existed?

Haresh told a very different story when he took the stand. There was never any handshake deal, he said, no oral agreement. Haresh Jogani is the 100% owner of J.K. Properties, he testified, and the other California companies that are in his name.

Sure, he testified, he had talked to his brother in 1995 about investing in Los Angeles real estate. Some aspects of the business were in writing. He had hired Shashi as a consultant, and the two had a written consulting agreement.

“He just was a consultant. It’s my corporation. It’s my capital, my business,” Haresh testified.

Other things in writing: declarations from the other three brothers in 2004 denying there had ever been a familial partnership.

“I am not now or have I ever been a partner in a partnership, member of an LLC, or shareholder, director or officer of any corporation or other entity that does business in California,” the declarations said.

Shashi’s lawsuit moved forward slowly, four against one.

But Shashi wasn’t the only one who felt he wasn’t getting his share.

Despite taking Haresh’s side, the other brothers also had similar complaints, according to their mother.

Kamlaben Jogani testified that her sons would complain to her about not getting their split of money from handshake partnerships with Haresh. She eventually told them she thought Haresh would not pay them. More than a decade after Shashi filed suit in 2003, the other brothers decided to switch sides.

Each filed suit against Haresh. While the four brothers were partners in their diamond business, Haresh controlled the money, according to the suits, which alleged he had forced them to sign the declarations writing Shashi out of the real estate deal.

In a suit filed in 2014, Shailesh claimed that Haresh warned Shailesh would be “financially cut off” if he refused to sign the declaration. The others agreed.

“‘If you don’t sign this declaration, then I’m holding your 95% capital,’” Haresh told his youngest brother, Chetan, according to Chetan’s trial testimony. “‘You will not get anything.’”

Kamlaben also changed sides. In an earlier deposition, she had said no deal existed between Shashi and Haresh. In 2017, at more than 90 years old, she said that she had lied. Haresh had threatened not to give money to the three other brothers if she did not obey him, she said.

“Everybody was scared of Haresh,” she testified in the 2017 deposition. “Even me, I would be scared of Haresh.”

At trial, Haresh denied pressuring his brothers and mother into taking his side.

It took 20 years and thousands of pages of briefs and depositions before the case finally got in front of a jury in September 2023.

How long a trial would take was another question. One juror asked if the trial would be done by the end of March.

“If not, we can hand out cyanide,” said attorney Steven Friedman, who with his father, Michael, represented Shashi.

It took five months. More than three dozen witnesses came and went. The trial was paused when the defense team contracted COVID-19. Just under 400 documents were presented as evidence.

Each brother testified except Shailesh, whose son Pinkal testified. Haresh’s defense team filed eight motions for a mistrial and moved to have the judge, Susan Bryant-Deason, disqualified. The defense said that the judge improperly took the side of the other brothers and made unfair rulings against Haresh.

In February, the case was left in the hands of the jury.

The jurors read out the verdicts in the silent courtroom. On one seven-page form, they answered questions about Shashi and Haresh. The first and most fundamental question was clear:

“Did Shashi enter into an oral or implied in fact agreement with Haresh to acquire properties as partners?”

The jury answered: “Yes.”

Jurors awarded Shashi more than $1.7 billion in monetary damages. Then an additional $1.5 billion in punitive damages. In the end, Shashikant Jogani was awarded about $7 billion, which included his 50% stake in the real estate companies he had helped build.

An additional $3.25 billion was awarded to Rajesh and Chetan, who also held partial ownership of the California real estate companies. Shailesh was awarded his stake in the partnership, but no separate damages.

Though the jury has ruled, the family drama has not ended.

“I believe this verdict is the wrong conclusion to the case and that it will not stand,” Haresh told The Times in a statement. “I’m confident in my legal team as they continue to advocate for what is right.”

His attorney, Rick Richmond, added, “The final chapter is far from written. In addition to eventual appellate review, there are several post-trial motions that may dramatically alter this verdict.”

Haresh’s team filed a motion calling for the disqualification of the judge, Bryant-Deason, who they say “zealously” advocated against Haresh at trial.

“She routinely sighed, rolled her eyes, and threw up her hands at Defendant’s counsel, including in front of the jury,” wrote Richmond in a post-trial motion. The motion also claimed she once “yelled at, walked out on, and pantomimed playing a violin” at one of Haresh’s attorneys.

In a response to the motion, Bryant-Deason denied she was biased.

Shashi’s lawyers are trying to find out how much money Haresh has and where he keeps it, but Shashi said the 20-year legal battle was not, at heart, about the money. It was about having his work recognized and his ownership of the company realized.

He still thinks there is a future in which all five brothers make amends. He hasn’t spoken to Haresh in a few years, since they tried to figure out a way to settle the lawsuit pre-trial. But maybe it is time to call up his brother again, he said.

“Haresh, look, whatever happens, happens,” he might say. “I have no grudge against you. ... I forgive you. What else can I say?”

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.