Student loan borrowers can slash their monthly payments — for now. Here’s what to know

- Share via

Student loan borrowers enrolled in a new federal repayment plan could see their monthly payments cut in half in the near future, thanks to a last-minute reprieve by a federal appeals court.

At the moment, though, the legal wrangling is sowing confusion throughout the student-aid system, with millions of borrowers’ monthly payments thrown into doubt. And the relief granted by the court was only temporary, so the Saving on a Valuable Education plan, or SAVE, may not be able to offer reduced payments in the long run.

“It is nearly impossible to know what to do at this point,” said Persis Yu, deputy executive director of the Student Borrower Protection Center. “Where we are is just not fair for student loan borrowers.”

The Education Department continues to work on a separate rule that would offer debt relief to an estimated 30 million student borrowers. But that effort will almost certainly wind up in court as well.

Here’s the latest on where things stand for borrowers with federal student loans.

What’s happening with student loans?

First and foremost, the only program affected by the legal turmoil is the SAVE plan, which is available just for federal student loans. Private loans and other loan repayment programs continue to operate as usual.

The SAVE plan was designed to lower monthly payments and, for borrowers who took out smaller loans, forgive debts sooner. Both of those efforts have been challenged in court by Republican officials from several states.

SAVE allows borrowers to make monthly payments based on their income, not on the amount they borrowed. In exchange, most borrowers have to continue paying considerably longer than they would under a standard plan, in which debts are paid off over 10 years. Under SAVE, the typical borrower makes payments for 20 years on undergraduate loans and for 25 years on graduate school loans. Then, any unpaid balance is forgiven.

As of July 1, monthly payments on undergraduate loans for those enrolled in the SAVE plan were scheduled to be cut in half, dropping from 10% of their discretionary income to 5%. But in early June, the Education Department informed borrowers whose next payments were due in the first half of July that they would be put into forbearance for one month while their monthly bills were recalculated. Their next payment would be due in August and, for undergraduate loans, based on 5% of their discretionary income.

Last week a federal judge in Kansas issued a temporary injunction, barring the Education Department from cutting the repayment rate to 5%. The department responded by telling 3 million additional SAVE participants that they, too, would be put into forbearance until August while their monthly payments were re-recalculated. Unlike the other borrowers in forbearance, though, these borrowers would have their repayment periods extended by a month, according to Natalia Abrams, president and founder of the Student Debt Crisis Center.

Then on Sunday, a divided three-judge panel of the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals put the injunction on hold pending the department’s appeal. It’s impossible to predict how long the relief will last because even if the department wins on appeal, the case could move on to the U.S. Supreme Court for possible reversal.

What should borrowers in the SAVE plan do?

SAVE plan borrowers who’ve received notices that they are in temporary forbearance will stay in forbearance until August. Some SAVE plan participants, however, had already received bills from their loan servicer for July that reflected the 5% repayment rate. These borrowers will need to make their payments this month, the department says.

The SAVE plan borrowers least affected by the legal back-and-forth are the estimated 4.5 million whose incomes are so low, their monthly payments are $0.

Borrowers unsure of where they stand should first log into studentaid.gov to see whether they’re enrolled in the SAVE plan. If they are, the next step would be to ask their loan servicer — whose contact information should also be available at studentaid.gov — when their next payment is due and how much they owe.

That could be hard to do, given how many other borrowers are also trying to contact their servicers. “From what I have heard, it is hard to get through,” Yu said. “If they can find out the information online, that is probably the ideal solution.”

Otherwise, she said, SAVE participants will need to wait for more information from the Education Department and their loan servicer, as uncomfortable as that may be.

Can borrowers in other plans sign up for SAVE?

Yes. The department temporarily closed its online application portal after the injunctions were issued, but loan servicers continue to accept the downloadable application form that the department makes available on studentaid.gov. Abrams said the department expects to reopen its online application portal soon.

In addition to payments based on 5% of discretionary income, the plan gives borrowers more breathing room by raising the amount of income considered nondiscretionary by 50%. And if the reduced monthly payment isn’t large enough to cover the interest that would accrue on the loan, the SAVE plan waives the excess interest charges rather than adding them to the borrower’s debt.

What about debt relief?

A federal judge in Missouri issued a temporary injunction last week against a provision of the SAVE plan that would have forgiven the unpaid balance after 10 years of repayments for anyone who borrowed no more than $12,000 in undergraduate loans. (Loan forgiveness would have been delayed by one year’s worth of payments for each additional $1,000 borrowed.)

That injunction was not covered by the appeals court’s stay.

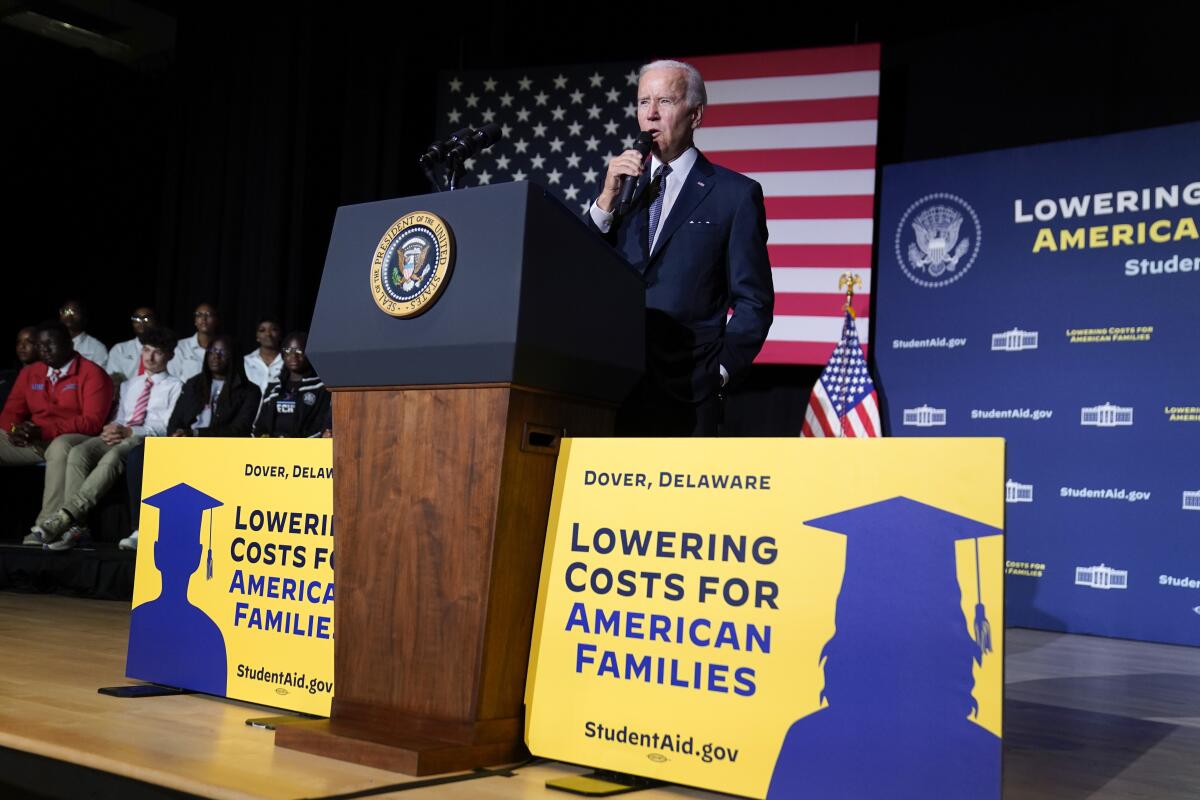

Separately, the Biden administration is finalizing a proposed rule that would cancel the debts for borrowers who’d been repaying their undergraduate loans for at least 20 years, or their graduate school loans for at least 25 years. Significantly, the rule would also reduce or eliminate the unpaid interest charges accrued by about 25 million borrowers, including all the unpaid interest by borrowers in income-driven repayment plans.

Although many of the people who filed comments on the rule supported it, Yu said, not all did. Opponents of Biden’s student debt relief measures have argued that it’s not fair to shift the cost of college onto taxpayers, many of whom made sacrifices to pay off their student loans.

Still, Yu said, even people who’ve paid off their loans “overwhelmingly support debt cancellation” because they understand how burdensome college costs have become and the struggles that borrowers face. “Young folks are unable now to start families, to buy homes, to start businesses, and that’s not what we want for future generations,” she said.

When the administration laid out its plans for student debt relief in April, it also said it would seek to partially or fully cancel the debt of borrowers who were experiencing financial hardship in repaying their federal loans. The administration has yet to propose a rule to implement that change, however, prompting more than 220 groups representing borrowers, workers, veterans, people with disabilities and consumers to submit a letter to the Education Department on Monday urging it to move ahead immediately.

“Tens of millions of borrowers were robbed of sweeping relief when the conservative majority of the Supreme Court struck down President Biden’s original debt relief program,” the letter says. The hardship rule “represents a glimmer of hope for the millions of borrowers and their families who have been forced to wait for nearly two years for much-needed relief,” it adds.

Abrams said that thousands of people have also written the White House to urge action now on the hardship proposal. If the rulemaking process starts too late this year, she said, implementation of the final rule would be delayed until next year — when Biden may no longer be president.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.