Latinx Files: When the anti-tourism movement hits close to home

- Share via

Periodically, the Latinx Files will feature a guest writer. This week, we’ve asked De Los contributing columnist Alex Zaragoza to fill in. If you have not subscribed to our weekly newsletter, you can do so here.

Recently, a friend who is white headed to Mexico City on vacation to meet up with another friend who was living there for a month as one of the growing population of “digital nomads” taking over the city. I told her to enjoy herself, but to be aware that there’s loud, and quite frankly understandable, backlash against American tourists in the country’s capital.

Over the years, gentrification has created untenable conditions for locals being priced out of their neighborhoods — this on top of the many issues that have long been present (corruption, police violence, organized crime, gender-based violence and femicide among them) in the country. While tourists blissfully peruse and extol the Michelin-star restaurants, designer stores and cool coffee shops, people are struggling.

More and more, the tourism industry is being seen as a blight and harbinger of problems for locals in Mexico, and that sentiment is being reflected elsewhere. Just this month, protesters in Barcelona squirted travelers with water guns as a call against the effects of mass tourism in the city. Chief among them were rising housing costs.

The comments on that news story included “Shameful,” “Never bite the hand that feeds you” and “Don’t abuse or harass innocent people.” God forbid your tapas get wet while locals demand the right to live a dignified life in their own city.

As I was telling my friend this, I realized I was basically giving myself the same reminder as my partner and I planned a trip to another destination plagued by the same issues facing Mexico City: Oaxaca de Juárez.

You’re reading Latinx Files

Fidel Martinez delves into the latest stories that capture the multitudes within the American Latinx community.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Among the aromatic panaderias, boisterous calendas and brightly-hued walls of post-colonial buildings were messages from the most frustrated, forgotten and marginalized people who call the picturesque city home: “A México su cultura y su gente se les RESPETA,” read one wall. Other taggings cut right to the point, with one reading, “Odio al gringo.” Another demanded that gringos “F— off.”

Already one of Mexico’s most visited cities, Oaxaca has experienced a 77% rise in tourists nationally and from outside of the country since 2020, according to the Oaxaca-based research organization the Center for Social Studies and Public Opinion. The post-pandemic-lockdown travel boom hit the city hard, and the research organization also reports that rents in the city center more than doubled in the last five years. Many who lived in these neighborhoods for generations have been forced out into areas that lack proper infrastructure, affecting their livelihoods.

In January, a protest organized by local activists in Oaxaca decried over-tourism, which they claim results in a type of gentrification that’s whitewashing the local culture and raising prices. Airbnb rentals are a major sticking point.

I nodded in agreement as I read the tags on pink and orange-painted walls, even as I walked the streets alongside my gringo boyfriend, displaying an act of cognitive dissonance that I’ve been unpacking for days. While we moved respectfully with acknowledgment of these issues, our presence could still constitute an act of complicity against an important resistance that I agree with. After all, I grew up in Tijuana, a city that has been affected by tourism on a cultural and systemic level.

León Lory Langle curates experiences for tourists in Oaxaca. The 45-year-old was born in Mexico City but relocated with his family when he was 9. He spent years working as a bartender before the COVID-19 pandemic led him to his current line of work. We met Langle on a daylong mezcal tour, during which his love of the region, deep knowledge of the agave-based spirit and his rooted personal connections made his enthusiasm infectious. The dude gets wildly giddy over agave plants.

As he sees it, Oaxaca has always been a destination. Vilifying tourists doesn’t sit right with Langle because he claims it’s locals who are raising the prices.

“It’s a complicated topic,” he said, after letting out a lengthy oof. “At the end of the day, the tourists will pay. Yes, all these problems and topics, it’s not just because of the tourists. It’s different factors that will create a movement.”

Langle argues that locals choose to raise the price of their rentals, or rent out their homes in the city center to companies that charge a higher rate. Everybody is making money, he says.

“It’s easier to blame foreigners than Mexicans,” he said. “In a tiny city, it makes sense. Pretty much everybody knows everybody. The majority are family. You don’t want to fight with your family. It’s easier to blame tourism.”

Pech, a trans tattoo artist born and raised in Oaxaca, doesn’t believe locals should shoulder all the blame.

“It’s not like this increase [in cost] that people who own cafes or other businesses are doing are going to realistically change the influx of gentrification,” they said. “In reality, it’s the responsibility of the state to create regulations. Gentrification responds to a structural system. It’s more than just raising prices. It’s a capitalist system.”

Pech points to the upcoming Guelaguetza celebration as one source of their frustrations. The annual festival highlighting local Indigenous cuisine and culture is a major tourist event.

“For that, there are resources,” they said. “It’s a whole month of parties because supposedly it brings in an outpouring of money from tourism. But that’s not money that the public sees.”

The event is steeped in hypocrisy, Pech said, arguing that Indigenous populations are routinely pushed off their lands, killed or imprisoned, becoming the victims of state violence. To put their culture for sale at a price that is inaccessible is infuriating.

“It makes me sad,” they said. “Seeing how much the place that I grew up in is changing in a way that’s more commercialized. I also feel anger.”

Growing up in Tijuana, I saw how much catering was done for tourists. There were many days where we woke up to no running water, relying on baby wipes to clean ourselves. Those troubles didn’t befall the hotels in the area. How much service we are expected to provide to the gringo builds resentment, especially when that comes with ridicule, mistreatment and a political system that targets us in inhumane ways — accommodation to the point of dehumanization.

And while I love to blame the gringos for everything (and they have much to be blamed for), this is also a local class issue. Middle- and upper-class residents also have this expectation of service, and those who perform those services are exactly who you might imagine: poor people, Indigenous people, darker-skinned people. Classism and racism are as abundant in Mexico as a hoarse throat at a Luis Miguel concert, or a mug shaped like a breast at a mercado de artesanias crawling with people wearing Tevas.

Despite my upbringing and fluent tongue, it’s dawned on me that as a white Mexican with some (not a lot of) disposable income and social capital, I might also be contributing to the problem. I also hold a genuine belief that we are better human beings when we embrace other cultures and places. These two seemingly incongruous ideas beg the following questions: How can we still explore the world without hurting anyone? How do we move about ethically?

“We aren’t against travel, but we are against tourism,” activist Andrea Bel.Arruti told Bloomberg after anti-gentrification protests were held in Oaxaca earlier this year. “What we’re against is tourism as a capitalist economic system that is based on a colonial model of extractivism of peoples’ resources, knowledge, ways of living and culture, where they are not the people that are befitting from this model.”

Some places perhaps should be left alone. However, Pech made the simple suggestions of being mindful of where your dollars are spent when traveling and always listening to locals.

As for me, taking a squirt from a water gun is the least I can do if it means supporting the most affected fighting for their rights.

— Alex Zaragoza

Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Stories we read this week that we think you should read

From L.A. Times

Daymé Arocena is bringing a Black woman’s voice to Latin pop

Daymé Arocena needed some space from jazz, the genre that helped her find her voice and jump-started her career, after leaving Cuba. Earlier this year, she released “Alkemi,” a Latin pop album that centers her experiences as a Black woman. Arocena spoke to De Los about how Beyoncé’s “Black is King” and an unexpected relocation to Puerto Rico shook her from her funk and helped her rediscover her spark.

And if you’d like to watch Arocena perform, she will be headlining a free concert on Saturday in downtown Los Angeles. Co-presented by De Los and Grand Performances, the show will be hosted by KCRW’s DJ Wyldeflower and will include a live performance from special guest Pan Dulce, featuring Alan Lightner. You can RSVP for the event here.

Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and a revelation about a rare LACMA portrait

For years, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art had labeled a rare portrait of Frida Kahlo as being from 1939. That recently — and quietly — changed after Times art critic Christopher Knight found an early photograph of the portrait in the Smithsonian American Art Museum archive that dates to 1935. Given the context of the two Mexican painters’ lives and relationship, Knight writes that the earlier date gives a new meaning to the piece.

Reparations for Chavez Ravine families? Not so fast, say some descendants

In March, Assemblymember Wendy Carrillo (D-Los Angeles) introduced the Chavez Ravine Accountability Act into the state Legislature. If passed, the bill would require the city of Los Angeles to erect a monument in honor of the families displaced from the area that eventually became home to Dodger Stadium. Assembly Bill 1950 would also establish a task force to look into the prospect of paying reparations to the descendants of these families. But not everyone wants restitution. For his latest column, Gustavo Arellano spoke with some descendants who would rather have their families’ stories told.

‘The Afterlife of Mal Caldera’ and other books by Latino authors we’re reading this month

For the July edition of “De Los Reads,” contributor Roxsy Lin spoke to Nadi Reed Perez about her debut novel, “The Afterlife of Mal Cabrera.” The book tells the story of the titular Mal, who navigates between the world of the living and the afterlife.

From elsewhere

Congressman Joaquin Castro calls for Latino film suggestions for National Film Registry

The office of Rep. Joaquin Castro (D-Texas) is once again accepting nominations for Latino films that should be considered for selection into the National Film Registry at the Library of Congress. As the chair of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, Castro was instrumental in the induction of “Selena” (1997), “The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez” (1982) and “Alambrista!” (1977). Out of the current 875 films in the registry, only 5% are Latino-focused stories. Story from Variety.

Asada Fest brings out the world’s best Latino chefs and taqueros to Los Angeles

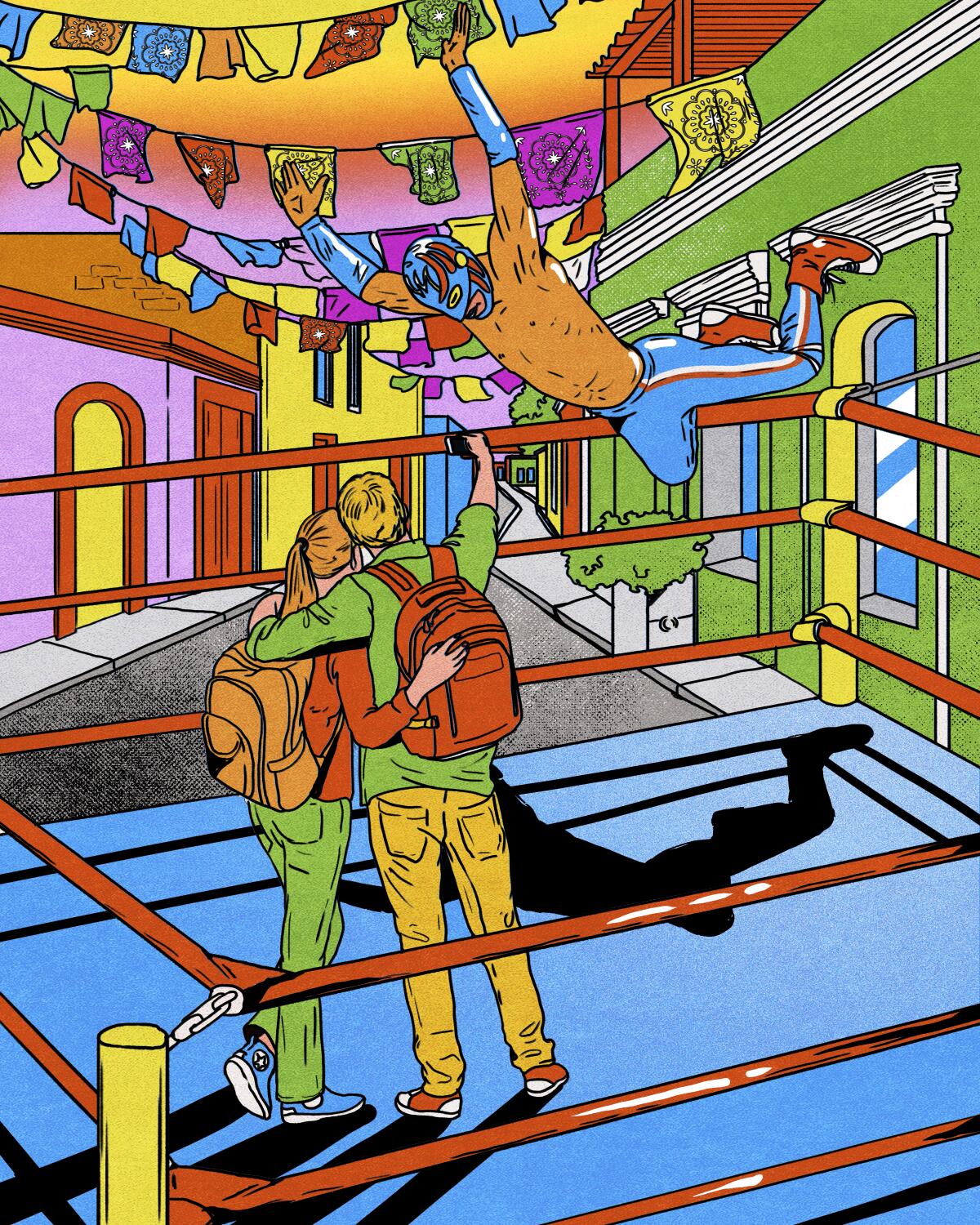

Over the weekend, Northgate’s Mercado Gonzalez hosted its first Asada Fest, bringing together renowned cooks from “Top Chef,” Netflix’s “Taco Chronicles” and Tijuana’s Culinary Arts School to the inaugural event. With tacos, lucha libre and live music, the Costa Mesa market continues to act as a community hub for Southern California’s Latino population. Story from Caló News.

— Cerys Davies

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.