- Share via

In the spring of 2021, I was riding the high of my first big break. I had just settled into a tiny bungalow in East Hollywood — my first L.A. apartment — when I began fielding calls from a slew of agents, managers and producers about optioning my life story for a script.

At the time, I felt like a hot commodity. The year before, I had become the first Latina to write a Rolling Stone cover story — a pandemic-era profile of Bad Bunny. By January 2021, I published a personal essay in Vogue about growing up tropigoth in 2000s Florida.

As I wrote in a previous edition of the Latinx Files, the seemingly discordant state of being a gloom-and-doom Latina was hardly that complicated to me. As the eldest daughter of Latino parents, I led a double life of sorts: I worked through high school to help out my family, yet still indulged in mischief at the mall, played in bands and experimented with witchcraft like many other American alternateens of the day.

With the launch of De Los, we are trying to explore the contours of Latinidad and what it says about our communities.

The TV pitch for my Y2K-era dramedy seemed bulletproof at the time. After all, the kids are wearing skate pants and listening to Deftones again! But after a few general meetings with non-Latino industry suits, who paired their sparse feedback with curious side-eyes, one prospective collaborator finally professed that my story was just too complex for gringos.

To sell a script, they explained, I would need to whittle down my experiences to either a feel-good immigrant family story, or a teen goth story; a script that showcased both facets of my world, despite being my actual lived experience, was simply not “marketable.”

Though it sounded harsh at first — and extremely telling of why the representation of Latinos in Hollywood remains abysmal — being unmarketable was not the worst thing in the world to happen to me. I self-published enough punk zines in my youth to shrug off the prospect of my life story being unpalatable to outsiders.

Yet as a Latina born and raised in the United States, I took pause at their reticence toward understanding my duality. In 2021, the Pew Research Center reported that nearly 1 in 5 people in the U.S. are Hispanic; more Hispanic people are being born here than immigrating here; and in 2021, 72% of U.S. Latinos ages 5 and older could speak English proficiently, up from 59% in 2000. If people like me are more common than ever before, what’s so hard to understand?

Get Involved

We’ve tried for years to articulate ourselves to outsiders: we’re bilingual, bicultural, “the best of both worlds.” Now, the term circulating across social media is “200-percenters”: a moniker that’s been adopted by young U.S. Latinos, from Becky G to Omar Apollo. Referring to themselves as “100% American and 100% Latino,” 200-percenters are those who were born in the United States yet proudly represent their Latin American heritage. It’s a quick, snackable descriptor for the many ethnically challenged among us; there’s no fumbling for the right words to describe nor validate your existence. We’re all sides of ourselves, all the time. (“Somos de los dos lados,” goes our motto here at De Los.)

Now, imagine my disappointment when I came to find the term “200-percenter” itself was a work of marketing, concocted in the lab of media conglomerate NBCUniversal Telemundo Enterprises. “They share the values of both cultures, are bilingual, and flawlessly jump between cultures,” reads the company’s definition of the 200-percenter. “This also makes them a valuable asset to companies who need to reach out to more diverse audiences every day.”

Arlene Dávila, professor and founder of the Latinx Project at New York University, is not buying it. “This is what marketers do,” she said to The Times. “They develop new labels for some new thing that they invented to sell... But we’re not some special new group. We’ve been here, and we’re no more complicated than anyone else. It’s fetishism.”

In her 2001 book, “Latinos Inc.: The Marketing and Making of a People,” Dávila warned of such cynical campaigns to define Latinos in marketing terms, pushed by “a global media industry that continues to dismiss Latinos as mere consumers rather than as active stakeholders who are worthy of jobs, opportunities, participation, and equity in these highly profitable cultural industries.”

The word “Latino,” as we know it, describes a loosely allied archipelago of nations once colonized by Spain and Portugal — each claiming its own cultural practices and dialects distinguished by borders. Dávila explains that once Latinos came to be in the U.S. — or, in the case of Puerto Rico and what used to be Northern Mexico, violently absorbed by it — Latinos of all nationalities were homogenized into one ethnic group.

Learning Spanish wasn’t part of a quest for identity. I was proud of this fact; that I was pursuing fluency on my own terms and not for cultural credibility.

Then, Latinos were racialized: not by their varying colors and phenotypes, but by the fact that they spoke Spanish. (Sorry, Brazilians!) This is how we ended up with Spaniards like Antonio Banderas playing Latin Americans in film, people rallying to use “Hispanic” as a race on census forms, and the problem of our representation being left to Spanish-language media to resolve. So long as companies like TelevisaUnivision got us covered — while famously marginalizing Latinos who are visibly Black, Indigenous and Asian — those making decisions in English-language media still believe they don’t have to.

“The reason why things haven’t changed in 20 years is because the racism hasn’t changed,” says Dávila. “We could make up 80% of the country. But insofar as we live in a racist world where Latinos are still regarded as a culture away from the culture — because being multicultural is not seen as American — we will continue to have this problem.”

Now, I can’t help but see the marketing everywhere. You know those jokes about kids who eat Takis for lunch in high school? It’s not just a time-honored tradition of U.S. Latinas — it’s marketing. The jokes about using Vick’s Vaporub to fight COVID-19? Also marketing. J Balvin bookending his songs with “Latino gang”? Marketing. The memes about getting smacked by your mom with a chancla? They sound like marketing, but they’re really just childhood traumas bubbling up to the surface.

Without being loyal consumers — whether of Patrón, of Goya, or bootleg Selena merch on Etsy — how can we distinguish our own identity as U.S. Latinos?

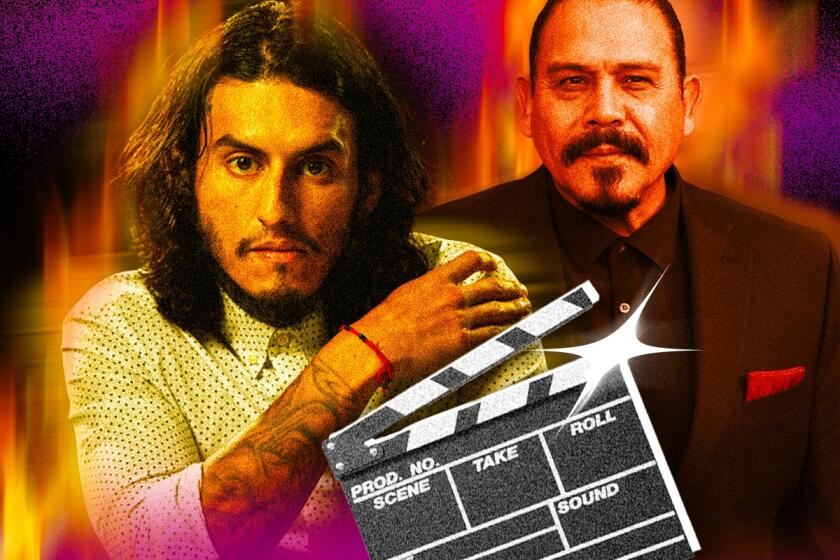

Why playing the stereotypical Latino role as a criminal is not a problem for some Hollywood actors.

Attempts have been made to mainstream us in Hollywood, but deep down, it feels like we’re still not even trusted to tell our own stories to their fullest. As soon as shows like “Los Espookys,” “Gentefied” and “One Day at a Time” showed the promise of a burgeoning Latino renaissance in the States, they were canceled. In one particularly stone cold case, HBO scrubbed “The Gordita Chronicles” — a beloved show executive-produced by Zoe Saldana and Eva Longoria — entirely from its platform, due to what a spokesperson described only as a “programming shift.”

The music industry has been much more encouraging. Many of the acts I’ve written about, such as Fuerza Regida, Grupo Frontera and Eslabon Armado, have remixed and revolutionized regional Mexican music from within the States; as Zack de la Rocha once did for rock, and DJ Charlie Chase did for hip-hop.

Yet online, feedback to U.S. Latino projects is peppered with an acutely venomous cruelty that dismisses our experiences, our Spanglish and other cultural hybridisms as “gringaderas,” which render us inauthentic in comparison to those born and raised in Latin America.

Meanwhile, gringos are eager to whip out their yardsticks and measure our cultural authenticity using the “spicy” 20th century-era marketing of Latinidad as a metric — or worse, they’ll cite whomever they partied with while studying abroad that one cuh-raaaazy summer in South America.

“Many Latinos, from the Afro-Puerto Rican to the Blaxican or part-Asian, feel they don’t fully belong anywhere. This sense of unbelonging is, in fact, what binds us,” wrote my colleague Jean Guerrero in a recent interview with Héctor Tobar, author of “Our Migrant Souls.”

Yet what also binds Latinos in the U.S., albeit less romantically, is geopolitics: We were brought together by the brutalities of European conquest, then later U.S. imperialism, and economic migration. “Latinos [are] a group of people who do have a shared experience... of mixing, of journeys, of surviving empire,” said Tobar. Love it or hate it, this makes for a fascinating, nebulous ether where even people as diametrically opposed as progressive Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) and conservative Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) share space — even if they don’t share viewpoints.

And though we may not be able to sell one distinct, unified culture to outsiders, what we do have is heart. I sense our connection in the spirit of activists fighting for the humanity of migrants and refugees — many of whom are, or could have been, our parents and grandparents. I hear it in the way someone else’s mother, recognizing the history in my face, calls me “mija.” I see it in the way we tend to quietly look out for one another at school, in the workplace or on public transportation, or the way we all lose our minds to the same songs at concerts. It’s these scenarios that give me hope, or at least something substantial to hold on to, as we work to redefine ourselves apart from consumer habits.

Maybe we U.S. Latines will never be fully marketable to people who refuse to understand us as anything but foreigners, even in our own birthplaces. Maybe that means I’ll never get to realize my dreams of making a totally twisted, A24 art-house film about my travails as a vampire freak in tropical paradise.

But if stories like mine can short-circuit the Hot Cheetos Industrial Complex and birth something honest and refreshing? Stories where the plot is developed beyond establishing that we exist? Stories where we get to be people?

Then I’m down to crash the system.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.