- Share via

One day at the beginning of summer, I was walking around Plaza Las Americas in Puerto Rico on my day off from work, when out of the corner of my eye I spotted a strange and fabulous-looking mannequin standing guard at the entrance of an antique shop. He seemed out of place at the mall, dressed in a floor-length royal purple cape that could have easily been either from the medieval ages or outer space, with chunky gold and turquoise jewels dripping off his neck.

At the Sears megastore 15 feet away, a steady trickle of afternoon shoppers streamed in and out, too busy with their bags and conversations to give the mannequin any attention.

I might have kept walking too, but I love costumes, drama. So I stepped closer, the cape pulling me in like a UFO beam. My fingertips buzzed as they grazed the rich, velvety fabric, while privately I wondered what the outfit cost. That’s when I saw it. On a plain yellow Post-it note stuck to the mannequin’s face, someone had casually written the five most incredible words:

CAPA DEL ASTROLOGO WALTER MERCADO.

I read the note again, and then again, a nervous, choking kind of laugh escaping my mouth. I felt like that lady who discovered the Virgin Mary’s face on a grilled cheese in the ‘90s. “Can anyone else see this?” I wanted to stop and ask everyone passing by. It didn’t make sense. The Walter Mercado’s cape! At the mall! How? And what?

I stumbled into the antique shop in a daze and soon found myself asking those same questions over and over. It wasn’t just a single cape. There was a closet’s worth. One with fur trimming and amber buttons that glowed under the warm overhead light, another with heart patterns made out of milky pearls. And aside from the capes, there were several tall glass cases filled to the brim with various of Walter’s possessions: perfumes still in their plastic wrapping, jewelry boxes, brooches, spiritual texts, at least three framed photos of the Hindu god Ganesh.

Maybe it was because of the name of the antique shop, Epoca de Abuelos, that I immediately thought of my abuela, a deeply religious Catholic woman who nevertheless refused to miss a single Mercado appearance on TV. This was in the 1990s, when he had a horoscope segment on the daily news, interrupting stories of rising crime and government corruption to give guidance to viewers from his gilded throne.

Back then, I didn’t understand Mercado’s impact on the average Latinx household. To me, he was simply the cool astrologer guy who dressed like a wizard.

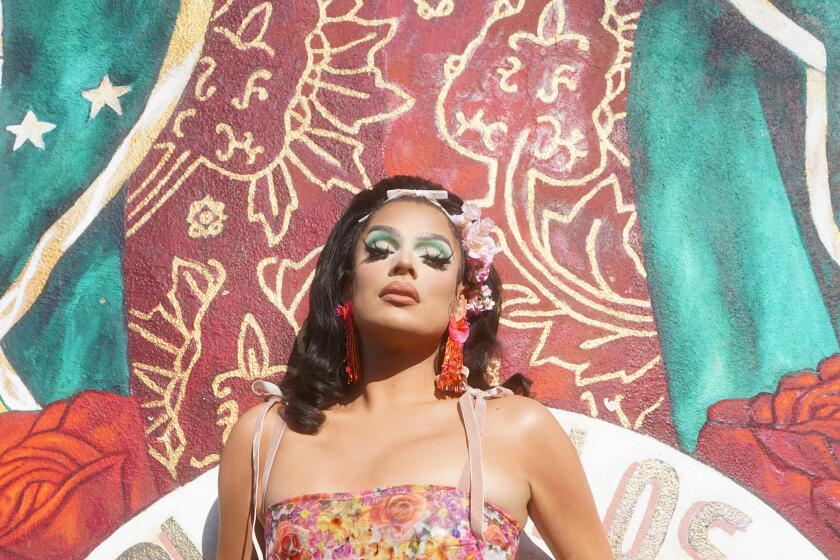

The co-host of ‘Drag Race Mexico’ sat down with columnist Suzy Exposito to discuss her illustrious television career, her Chicana pride and the freedom of being nonbinary.

Much can be said about Mercado, who was also known by the stage name Shanti Ananda. He was an international icon, according to some estimates reaching an audience of more than 120 million people at the peak of his career. A trailblazer, bringing his brand of mysticism and worldly spirituality into countless Catholic household.

A businessman, with books, DVDs, audiotapes, zodiac-themed soaps and, at one point, even a dating website under his belt.

But what I remember most fondly about him were the looks he pulled: appearing on screen every day in a gorgeous new cape, hands decked out with shiny rings he waved in hypnotic circles to cast spells on viewers, his white-blond hair feathered around him like a halo.

Though Mercado never claimed to be queer — a master at dodging labels, “I have sexuality with the wind,” he once famously said — for years, I found hope not in his horoscopes, but in his mere existence. He may not have pronounced himself gay, but as a child I believed that if my Jesucristo-adoring abuela wasn’t bothered by a man wearing a little mascara, maybe one day she wouldn’t be bothered by the secret I carried in my own heart.

A decade later, as I wandered around the shop admiring Mercado’s belongings, in awe of their fierceness and unapologetic glamour, I felt the same thing I did when I watched him on TV as a kid: safe.

A week or so after I first learned about his capes, I took my friend Jose, who also goes by the name Paca, to the mall. Though only in his mid-20s, Paca is my friend who reminds me most of Mercado. A rabid collector of thrifted ‘80s blazers with built-in shoulder pads and anything sequined, he works at a drug rehab center, where, like Walter, he shares his infectious zest for life with people needing a little extra love and support, all the while looking like a character out of an old-school novela. I can’t count how many times I’ve seen my friend get stopped in the street by a former patient, with whom he always has a minute to share a cigarette and dirty joke.

The inclusion of a Colombian American drag queen has put the National Museum of the American Latino in jeopardy.

“Who am I to judge anyone?” Paca frequently says, shimmying his giant shoulder pads and blowing smoke out of his glossy lips. He’s one of my favorite people in the world.

We’d decided to make a big day of visiting the capes, making a pit stop at a coffee stand inside the mall before heading over. This was as meaningful to us as any religious mecca, so we took our time. We sat for an hour, sipping on cafecitos like a pair of tías, talking about Mercado and what he meant to us. Paca had a story like mine: in his childhood home, the moment Mercado’s segment started on the news, his family dropped everything and rushed over to the TV.

We eventually made our way to Epoca de Abuelos. The two of us wandered around the shop gasping as we inspected Mercado’s objects: the gold coins, the rings, the bangles. When the coast was clear, Paca smiled mischievously, slid one of the capes off a mannequin and put it on.

“Ugh, I need it!” he sighed, doing a twirl. “I mean, I have to have it!”

Watching him, I knew Mercado would have wanted Paca to have it too — but the price tag listed the cape at over $800. We checked the others. $1,000. $1,300. They were way out of our budgets, yet at the same time, they still seemed slightly cheap to me. These weren’t just any capes, after all. They were Mercado’s! The lady with the Virgin Mary grilled cheese sold it on EBay for $28,000. Surely Mercado’s capes were worth more than a sandwich. I found a couple of them in the back of the shop, hanging on a rack inside blue trash bags. Did his legacy not mean anything? I asked Paca, who shrugged, took the cape off and simply said, “One day.…”

Over the next few months, I continued visiting Mercado, sometimes bringing a cafecito along, paying my respects as I would at a relative’s grave. Other times, I’d hop in before heading to a movie at the theater down the hall, just to say hi. On one of those visits, the shopkeeper, a stylish older man with white hair and gold glasses, approached me to see whether I needed help.

My curiosity got the best of me, and I asked him how he came to be in possession of Mercado’s objects. The owner nodded politely, as though he’d been asked that before, and said he used to clean Mercado’s fish tanks when the astrologer was alive. He spent a good amount of time at his house and got to know him and his family well. When Mercado died, one of his nieces reached out to him wondering whether he’d be able to help sell a few of his items from his estate.

I admitted to the shopkeeper how torn I felt. On one hand, it was cool that any Puerto Rican could walk into the mall and have access to such treasured items. On the other, didn’t the legend deserve to have his things preserved in a museum with security or something?

Buried underneath that question was the one I really wanted to ask: Were Mercado’s things being treated so casually because the astrologer had, well, “sexuality with the wind”?

Get the Latinx Files newsletter

Stories that capture the multitudes within the American Latinx community.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Many of the capes, the shopkeeper happily informed me, had indeed been sold to museums where they would be displayed in positions of honor; the capes I’d seen in the blue bags were, in fact, awaiting to be sent to Las Vegas. What I saw at his shop were the stuff nobody had purchased yet since Mercado’s death in 2019. But, yes, he agreed, Walter’s things are special.

He told me about a woman who’d been walking by the store one day and came to a sudden stop, not knowing why, later realizing that it was Mercado’s energy calling out to her. About a santero from Caguas who swept in to purchase Mercado’s meditation altar. And another customer who’d bought several of Mercado’s perfumes. “They’re years old, probably expired,” the shopkeeper said, “but he came in here looking for more, and you know what? They still smell good.”

I asked him if I could see a ruby brooch I’d had my eye on for some time. As I held it, the shopkeeper must have understood how important Mercado was to me, because he let me have it at the discounted price of $40. That day, I left the shop feeling grateful to have a small piece of Mercado’s legacy that I can carry with me, to give me courage when I’m down and hope to cut through all the bleak news days. But a legacy is more than a physical object, more than a costume. Mercado’s real legacy lives on in the people he touched, who are a little freer today because he refused to let anyone dull his shine when he was alive.

I called Paca. It was barely 4 o’clock, but I was in the mood for cocktails.

My friend giggled into the receiver. “Who am I to judge?”

The two of us spent the night dancing at a gay bar. At one point, I thought about the words Mercado used to end his segments with: Les deseo paz, mucha paz, pero sobre todo, mucho mucho amor. My heart ached a bit, feeling the loss over again, but I feel better knowing that his wish came true. I had peace, lots of peace, but more than anything, lots and lots of love.

Edgar Gomez is a Florida-born writer with roots in Nicaragua and Puerto Rico. They are the author of “High-Risk Homosexual,” winner of a 2023 American Book Award, a Stonewall Israel-Fishman Nonfiction Book Honor Award and the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Memoir. Their second book, a memoir about growing up poor in early 2000s Florida titled “Alligator Tears,” will be out in 2025 from Crown. They live in Queens, N.Y. Find them across social media @OtroEdgarGomez.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.