- Share via

Alanis Ruiz Guevara was 8 years old when she was sent home from her private school in Ponce, Puerto Rico, for wearing cornrow braids.

“I was so scared and I felt so bad,” Ruiz Guevara said, who identifies as Afro-descendant. “I felt like there was something wrong with my hair.”

Now 25 years old, her experience is the driving force behind a new bill in Puerto Rico that prohibits discrimination against natural hair and protective hairstyles in both private and public institutions.

“Puerto Rico needs legislation that protects people who wish to wear their hair naturally or in African styles, which is a personal decision that has nothing to do with our creative, intellectual, or professional performance,” said Ruiz Guevara in a statement following the measure’s approval last Wednesday.

A new wave of Afro-Latina entrepreneurs are embracing their natural hair and creating products that cater to curly and textured hair.

Puerto Rican Gov. Pedro Pierluisi signed Senate Bill 1282 ordering all establishments to adjust their regulations to highlight this public policy, but efforts to implement the bill have been in the making for more than three years.

Following the incident in grade school, Ruiz Guevara said she used relaxers to straighten her curls. Recent studies show that chemicals in hair-straightening products have been linked to cancer.

“Then when I started straightening my hair, my classmates would say that it smelled like chemicals,” Ruiz Guevara said.

However, upon joining in a youth program by Colectivo Ilé and Revista étnica called Afro-Juventudes, which promotes anti-racism learning for Afro-descendant youth on the island, she realized bias against textured hair was a collective experience that needed to be addressed at a more systemic level.

“It was something that other people also were struggling with on the island and had even worse experiences than I had,” Ruiz Guevara said.

Latinidad can be expressed in multiple ways, and these Latinx entrepreneurs are using their nail art businesses to showcase their culture.

The youth program is also where she learned of the CROWN Act, which stands for “Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair.” The California law prohibits discrimination based on protective styles and textures. Though it failed to gain federal approval, it has inspired similar codification in 26 states.

“I realized that it would be really nice to have a project like this in Puerto Rico,” Ruiz Guevara said, who at the time was studying political science.

As an intern with Jóse Bernardo Márquez of the Puerto Rican House of Representatives in 2021, Ruiz Guevara introduced a similar petition inspired by the CROWN Act known as the “Law Against Hair Discrimination,” but the measure was left at a standstill for two years.

“I realized we needed to do something because otherwise the project is just going to die there,” Ruiz Guevara said.

Undefeated, Ruiz Guevarra revamped her proposal with the help of Mentes Puerto Rico en Acción, an initiative that helps young people create social projects on the island, where she now works as a coordinator. At the same time, she formed an anti-racism activist group called Colectiva de Resistencia Cimarrona, to address systemic racism and promote the bill.

From body to birth workers, and life coaches to spiritual guides, the Latinx community abounds with healing arts practitioners offering relief.

In updating her petition, Ruiz Guevarra used U.S. data regarding hair discrimination gathered from the CROWN movement to strengthen her Puerto Rican proposal.

Among the statistics used was that 80% of Black women in the U.S are more likely to change their natural hair to meet social norms or expectations at work. The petition also used empirical evidence gathered in Social Psychological and Personality Science magazine that proved a bias against natural Black hairstyles in the workplace.

The proposal eventually garnered attention from Sen. Ana Irma Rivera Lassén, the island’s first Black female senator. Alongside Sen. Rafael Bernabe Riefkohl, she reintroduced the ban against hair discrimination in August 2023.

Its revival initially sparked debate from local government officials at a January hearing who felt that the island’s laws already prevented discrimination, alongside Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. The idea was also met with pushback at public hearings, mainly from private corporations and institutions, said Ruiz Guevarra, but it ultimately opened the door for more public conversations regarding race.

“There’s a lot of people that don’t think there’s a problem mainly because they haven’t experienced it,” Ruiz Guevara said. “We haven’t had these conversations regarding this type of discrimination that at the end of the day is rooted in racism.”

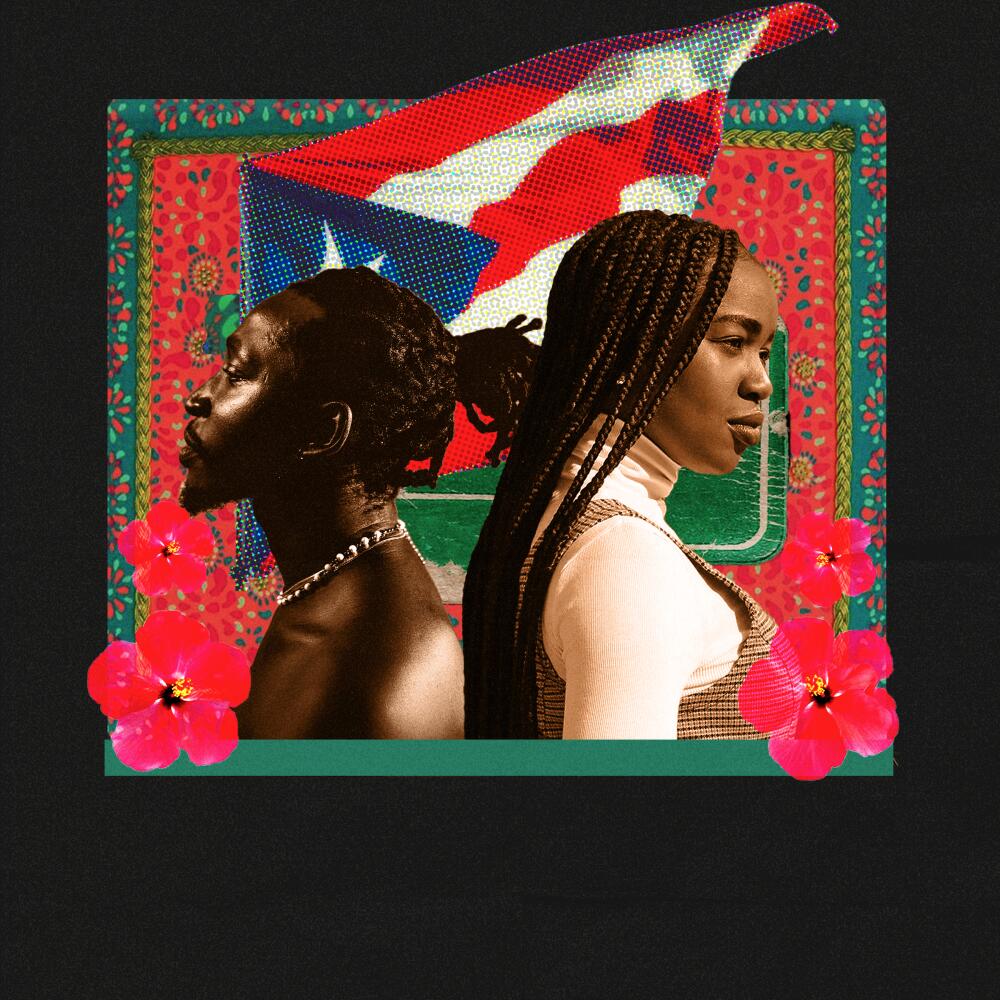

Cuban singer Daymé Arocena embraces the sounds of Latin pop on her newest album, ‘Alkemi,’ making her experiences as an Afro Latina the focus of the project.

Olga Chapman Rivera, communications director at Corredor Afro, one of the 30 organizations that supported the measure to preserve cultural heritage among Afro-descendants, said the reception to the idea was mixed.

“It reveals a reality of the country, that there is still a job that needs to be done to address racism,” Chapman Rivera said. “Race is not a topic that is discussed daily like it is in the U.S.”

Chapman Rivera said there’s a widespread myth in Puerto Rico that everyone is equal parts indigenous Taino, African descendant, and Spaniard.

“What that narrative does is make race invisible to the African part of the country and hides the profound racism,” Chapman Rivera said.

According to the U.S. Census, more than 1.6 million (of 3.2 million) Puerto Ricans identify as being of two or more races and 230,000 identify solely as Black.

Hair plays a major role in how Afro-descendant communities protect and honor their cultural heritage, a perspective that is shifting in Puerto Rico. For example, one shampoo commercial in April indicated how cornrows were historically used to map out escape routes by enslaved individuals.

“Braids have ancestral meaning to us,” Ruiz Guevara said.

Now that the law has been approved by island changemakers following hundreds of calls and letters of support for the statute and a May campaign titled “My Hair Is My Crown,” Ruiz Guevara said the real work starts now in ensuring its implementation and other anti-racism policies.

“It has to begin with creating more policies against discrimination,” she said.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.