Six music documentaries that will have you singing a new tune

- Share via

This year finds an especially wide and eclectic array of fine documentaries centered on the music world. The Envelope spoke to a medley of directors of awards contenders about their challenges, surprises, methods and more.

‘SUMMER OF SOUL’

In “Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised),” Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, co-founder of hip-hop band the Roots and first-time film director, deftly revisits 1969’s summer-long Harlem Cultural Festival, which featured such blazing talents as Stevie Wonder, Mahalia Jackson and Nina Simone. Thompson spoke by phone from his L.A. hotel room about his joyous film.

With 40 hours of concert footage to work with, how did you zero in on a narrative structure?

“In the beginning, I [thought], ‘Let’s just make this a straight concert film. [But] once we really got deep into 2020 … and the more that the news we were living in was parallel to what was happening 50 years ago, I realized that I had my connection [to a narrative].”

How did you put your special Questlove musical stamp on the film?

My producer, Joseph Patel, said, “What would you do if this was a DJ gig?”… So I asked myself, “What do I want to leave people with?” I wanted them to leave on fire… I [also] knew the first five minutes had to be like, “Oh, my God, the drummer from the Roots did this thing?” The answer came in the form of that drum solo by Stevie Wonder.

Any surprises about the concert as you went along?

I found out that Aretha Franklin was an 11th-hour no-show. Jimi Hendrix tried to get on the bill … but got rejected. Also, the [festival’s] final week was never recorded because the camera crew had already been hired to shoot the pilot to “Sesame Street.”

‘BILLIE EILISH’

Veteran filmmaker R.J. Cutler turns his cameras on one of the planet’s biggest — and youngest — pop stars in “Billie Eilish: The World’s a Little Blurry.” He chatted by phone from his Melrose Avenue office about capturing Eilish amid her stratospheric rise.

What was your greatest challenge making this film?

The challenge is always the same in vérité … to earn and maintain the trust of your subject.

Cinematically, how did you approach the musical performances?

I was interested in a shooting style that harked back to [musical documentaries] “Don’t Look Back” and “Gimme Shelter.” The way those performances were filmed … the intimacy is what we were aiming for … being in the moment with Billie and understanding her emotionally.

How much creative input did Eilish have?

I had final cut. But there’s also a fundamental understanding that one has as a vérité filmmaker: The story doesn’t belong to me. This is Billie’s life, not my life. I’m very respectful of that.

What was Billie’s response when she saw the movie?

She said, “I didn’t think anyone could possibly understand what I was going through. And that’s what this film shows.” It’s one of the greatest compliments a filmmaker can get in a situation like this.

‘KAREN DALTON’

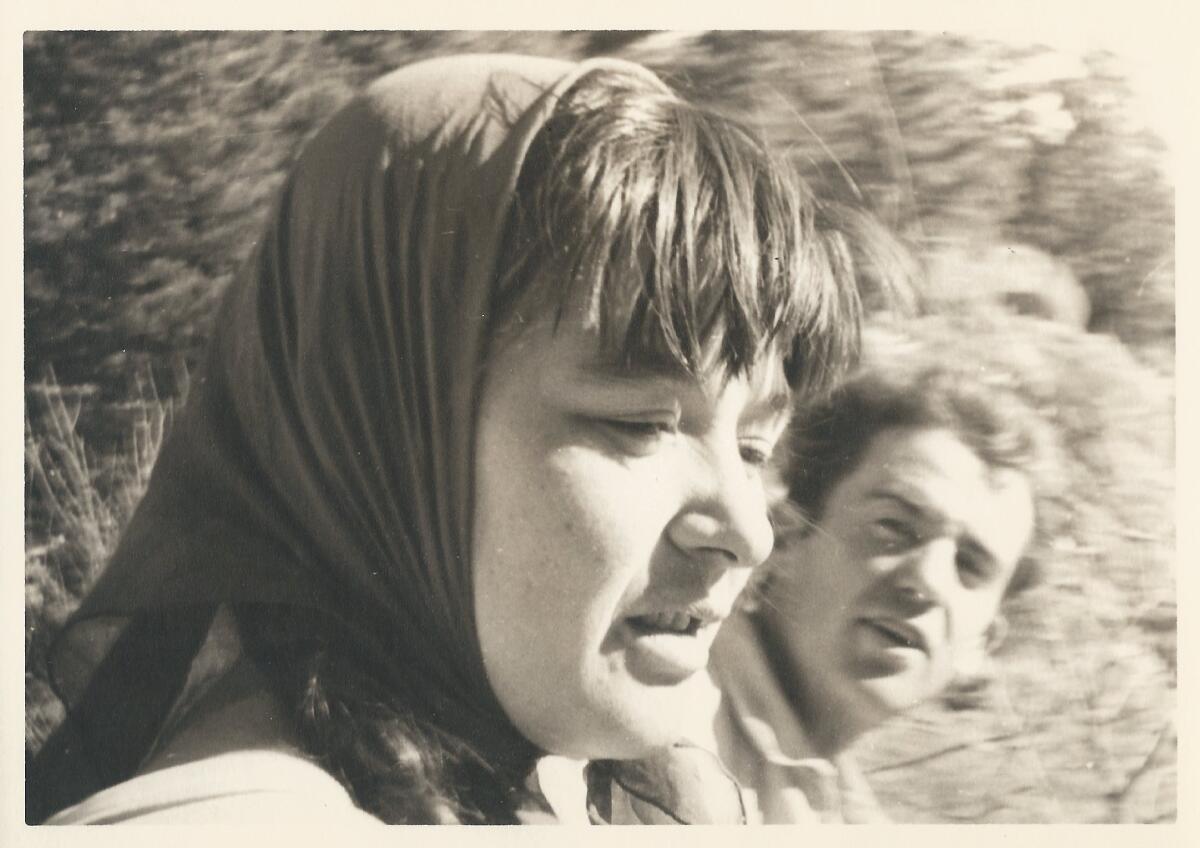

Karen Dalton made her mark on the 1960s New York music scene with her bluesy folk tunes and distinctive vocals, but her unconventional ways and drug addiction led her into obscurity and an early death. Co-directors Robert Yapkowitz and Richard Peete called in from New York to shed light on their “passion project,” “Karen Dalton: In My Own Time.”

What was the hardest part of telling Karen’s story?

Peete: That Karen is dead and we couldn’t interview her and give her a voice.

Yapkowitz: Karen lived a very nomadic life; the information is very fragmented. We came to the conclusion that we were going to embrace the gaps and not try to imagine what we don’t know and try to celebrate what we do know.

Most surprising thing you discovered about Karen?

Peete: That she was so charismatic. That she had high energy and was playful. On the internet, all you hear [is] that she was a tragic figure and all these sad moments of her life.

How did Karen’s music affect your stylistic approach?

Yapkowitz: There’s this hypnotic, almost fluidity to Karen’s music and we really wanted the film to be in sync with that. We just thought it would help bring you closer to her.

What didn’t you want the film to be?

Peete: We didn’t want to just make a film about Karen that was filled with contemporary musicians … just talking about how much they liked her. We had to try to find new approaches to telling the story with what [limited] elements we had.

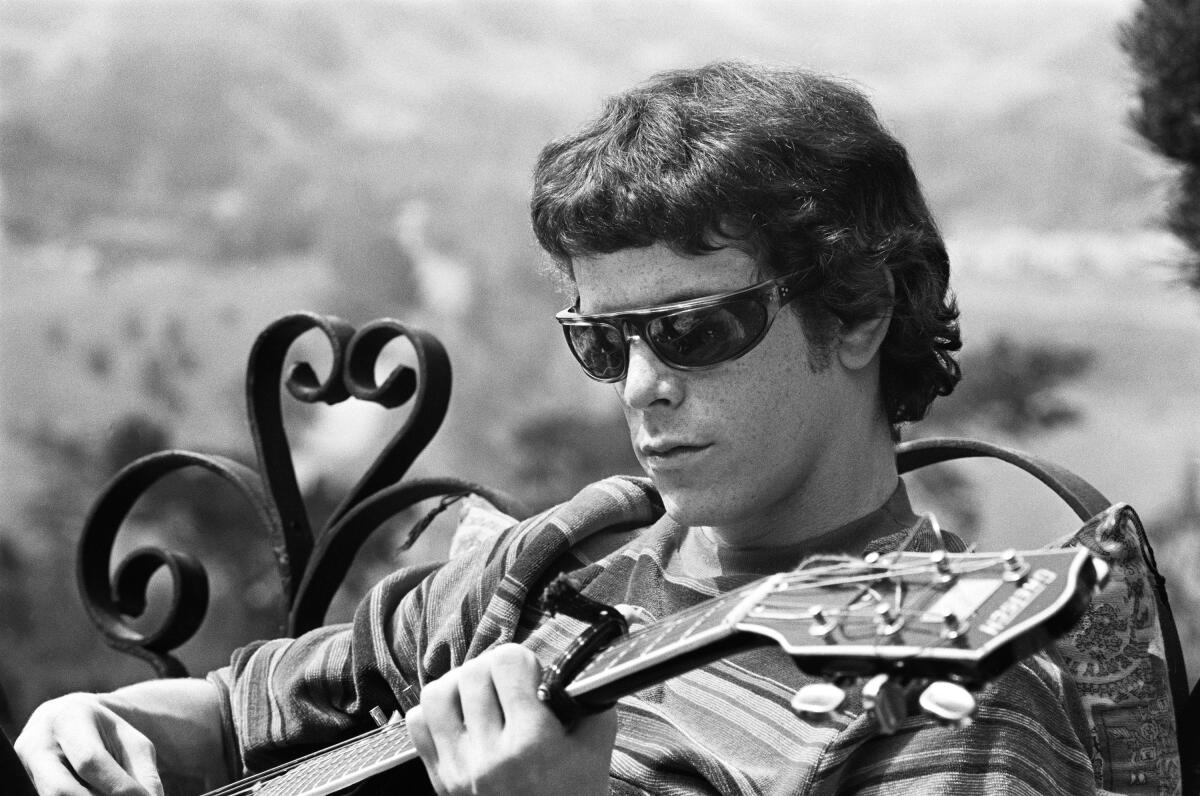

‘THE VELVET UNDERGROUND’

Writer-director Todd Haynes inventively revisits one of the 1960s’ more undervalued yet influential avant-garde rock bands, the Velvet Underground, founded by Lou Reed and John Cale. Haynes spoke by phone from his L.A. hotel room about his kicky, kinetic film, “The Velvet Underground.”

The movie covers such a large canvas. What was your biggest challenge?

With the Velvet Underground as a subject, you don’t have concert footage, you don’t have the traditional promotional materials. It was a total creative opportunity and invitation to say, “Let’s embrace what’s absolutely distinct about this band and make that the language of the filmmaking and the film.”

How did the band’s music affect the vibe of the film?

My mantra was to let the music and the images lead your experience. To make that music feel fresh and have people understand what made it sound different in the time that it came out of — what was risky about it.

With Lou Reed no longer alive to tell his story, what were your impressions of him?

[That] he was a totally contradictory person from the very beginning. He had a lot of aggression and a lot of hostility. He had an insatiable curiosity to explore places and experiences that other artists wouldn’t necessarily explore. [Yet] he was also somebody who wanted to be successful.

How was it to work through so much amazing archival material?

It was such an enjoyable process but also remained overwhelming. I never felt a master of all this material. You’re still a subject whose blind spots are also part of the artistic point of view.

‘LOS HERMANOS/THE BROTHERS’

Producers/co-directors Marcia Jarmel and Ken Schneider follow Cuban-born, classical musician siblings Ilmar Gavilán and Aldo López-Gavilán in “Los Hermanos/The Brothers.” The filmmakers hopped on the phone from the Bay Area to talk about their warm and buoyant portrait.

OK, greatest challenge in a challenging project?

Schneider: The logistics of travel [to and from Cuba] due to our country’s limitations and laws.

Were the brothers at all hesitant to be your subjects?

Jarmel: Ilmar is a kind of natural storyteller, so he was immediately in. Aldo is a more internal person. I think he was a little more cautious about getting involved.

How did their gorgeous music shape your filmic approach?

Jarmel: The music very much was a framing device and we sort of see it as a character in the film. We organized the film something like a musical suite: kind of each beat in the story had its own music.

What would you like audiences to take away from the film?

Schneider: That it’s better to remove than to erect barriers and that where politics fail, culture can succeed.

‘THE SPARKS BROTHERS’

Pairing puckish, ingenious director Edgar Wright with equally clever and distinctive pop duo Ron and Russell Mael (band name: Sparks) was a match made in documentary heaven. Wright Zoomed in from New York City to chat about “The Sparks Brothers,” his dazzling look at these playfully inscrutable musicians.

Given Sparks’ more than 50-year career, how did you begin to lay out their remarkable tale?

I always felt like the best way to do it was to tell the entire story. They never broke up, they kept on going. As you’re telling the story of Sparks you’re seeing the culture change at the same time. And that was really interesting to me.

How did Sparks’ unique music inform the filmmaking?

If there’s something that carries through all of Sparks’ music [it’s] the sense of humor. I felt [the film] should be as enjoyable and entertaining as listening to a Sparks record.

As musicians, the Maels have been famously in control. How were they to collaborate with for a film?

They left me to it. They helped out in the sense of some suggestions of people to talk to [as interview subjects] and in terms of their archive, which they were really helpful in terms of sharing. They were just really accessible.

But they’re also famously enigmatic, no?

There were a few things they didn’t really want to talk about, and I respected that. I think sometimes other musical stories or documentaries get too bogged down in soap opera rather than the art. [The Maels] are all about the work.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.