Documentary examines how what the U.S. did -- and did not do -- helped shape the Holocaust

- Share via

Documentarian Ken Burns says he could be given a thousand years to live and he’d never run out of topics to examine in American history. But of the Emmy-nominated “The U.S. and the Holocaust,” directed with Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein — an unflinching three-part exploration of how America responded during that horrific time — Burns says, “I won’t work on a more important film.”

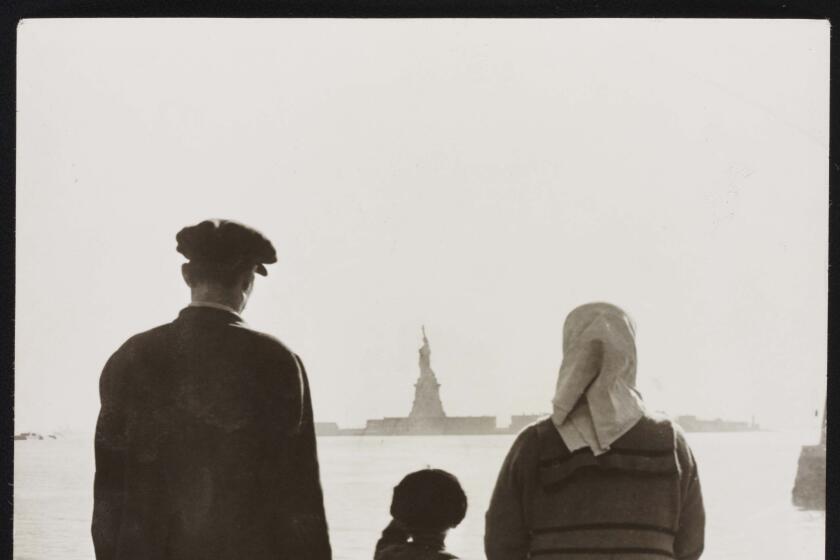

After their “The War” (about World War II) and “The Roosevelts: An Intimate History” inspired a need for clarification as to what Americans thought, did and didn’t do about the Holocaust, the trio opted for a deep dive follow-up that would parallel the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s similarly themed exhibition. What Burns, Novick and Botstein soon realized, though, was that a sweeping, freshly researched retelling of the persecution of European Jews would be just as essential to their ever-lengthening film as detailing the xenophobia, racism and political decisions that made American inaction toward refugees so tragically consequential.

“I thought I knew a fair amount about the history,” says Novick, who also co-produced. “But the more we dug into it, the more we realized we didn’t know that much, and we learned the parallels and complexities of what was going on in Europe versus what’s going on here.”

Filmmaker Ken Burns’ latest documentary series, ‘The U.S. and the Holocaust,’ draws parallels to the recent rise in American nationalism and antisemitism.

Botstein, a longtime Burns/Novick producer earning her first directing credit for “The U.S. and the Holocaust,” remembers trepidation at revisiting the Holocaust as a documentary subject, until the film revealed itself as eerily resonant with today’s anti-immigration climate, “and how a wildly civilized democracy can crumble very quickly,” she says. “I think it morphs into a film about immigration refugee policy. The Holocaust is a devastating, hugely important way to think about it.”

Burns cites two factual parallels as guiding the film’s historical narrative. “There’s the pervasive anti-Semitism of the country,” he says. “Henry Ford thinking Jews were responsible for the death of Abraham Lincoln. The fact that [a majority of Americans] didn’t want to let anybody in, even after they saw the movies at the end of the war of the gas chambers. That hurt me deeply. Where was our soul? Our conscience?”

The other he calls “the metronomic terror” of the Holocaust. Burns says the oft-cited descriptor “6 million” has no meaning anymore, that conveying the size and scope of the killing necessitated particularizing it: family stories told by survivors, where some make it to other countries, but most don’t. “You say, ‘Two out of every three died,’ or you look at a newsreel of an attractive young Jewish woman looking out a window, her parents join her for a second, and you realize, two of those three people are gone,” says Burns. “What was the lost potentiality? What symphonies weren’t written? What cures weren’t found? What children weren’t raised with love?”

Even Anne Frank’s father, Otto, couldn’t get his family into America, another of the film’s eye-opening revelations. “Otto was well-to-do, he had contacts in the United States, he wasn’t going to be a burden on the state,” Burns says. “And he still couldn’t get in. She could be alive today.”

It was also crucial for the filmmakers to portray Franklin D. Roosevelt’s role in the country’s turning away of refugees as more nuanced, and look at the big picture of rising isolationism, the Depression’s wake, and a stingy Congress about the humanitarian crisis. “It’s incredibly complicated,” Botstein says. “He’s a political being. It’s definitely not anyone’s best moment, but to wildly dismiss him makes no sense, either.”

Burns says holding Roosevelt’s feet to the fire ultimately led to an admiration of his realpolitik, that staying in power — not doing things he believed in — eventually made a difference. “You go back and forth [on him], but in Episode 3, when he gives approval to the War Refugee Board, the single greatest organization for saving human beings in the entire history of the Second World War? That’s not a bad thing.”

A brain trust as storied and thoughtful as the Burns/Novick/Botstein team has long been an asset in today’s documentary landscape. But production on “The U.S. and the Holocaust” became stressful when Burns, absorbing the anti-democratic swerve in America during the chaos surrounding the 2020 election and the Jan. 6 insurrection, felt the film should be finished one year earlier than scheduled. [PBS premiered it last fall.] “We needed to get this out,” Burns says, citing Mark Twain’s observation that history may not repeat itself, but it often rhymes. “When we began this in 2015, it was a different United States. But it needed to be part of a national conversation about authoritarianism and these painful rhymes in history.”

Pretending the U.S. was on the sidelines won’t make us a stronger nation, but taking responsibility will.

On top of that, all three filmmakers agree it’s a disturbing time to be unearthing past wrongs in the effort to forge a better future, when of late the very teaching of accurate history itself is being attacked.

“Jefferson said we’re disposed to suffer evils while evils are sufferable, so this is going to take extra effort,” Burns says. “And it seems we have obstacles set before us now, people saying, ‘Don’t worry about slavery. Don’t worry. We’ll make your trains run on time.’ And that’s the road to authoritarianism. That’s why a vigorous, open, debated, suffered, joyful history is our birthright.”

Novick says the response to their film across the political spectrum has been reassuring. But she stresses, “We’re not going to put our thumb on the scales, as Ken always says. We’re going to try to understand what happened. And that can be a really positive force. These are uncomfortable truths, and we have to face them. And if you don’t think people should know this? All the more reason why we’re going to make sure people do.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.