This election year has been so fraught with outsize storylines that reading the news can feel like reading a thick novel. An assassination attempt on a presidential candidate. A late-game withdrawal by a sitting president, followed by the immediate ascension of his successor. We live, as the old expression wishes (or curses) us, in interesting times.

Not to be outdone, the Emmy season is packed with its own political intrigues, and not just the kind that generally accompany jockeying for awards. As the country prepares to select a new president, it seems fitting that some of the most nominated series are fueled by the art, strategy and down-and-dirty combat of politics. On TV, as in life, it’s a full-contact sport that requires subterfuge and constant toggling between public and private identities. In the most extreme cases, as in the most garlanded show of the year, politics are a matter of life and death.

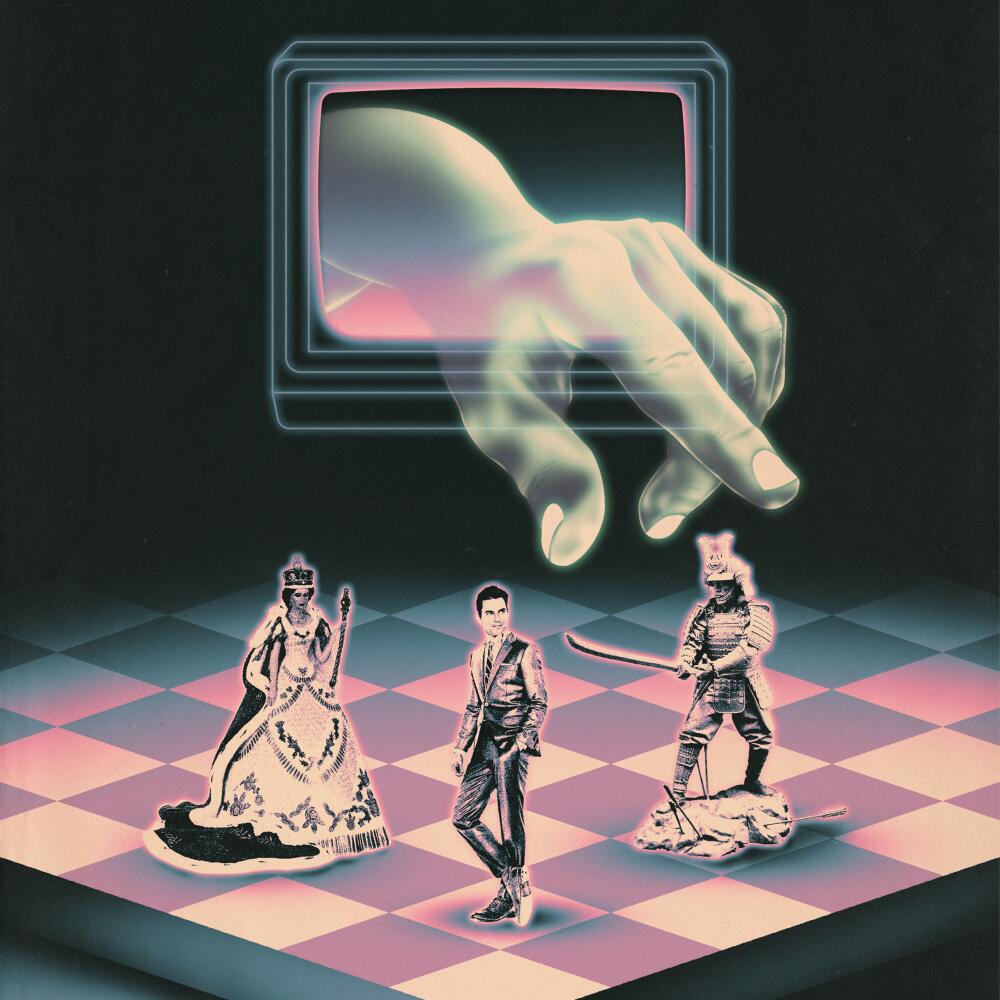

The political gamesmanship in “Shōgun” is so intricate you might need a scorecard, or at least a good recapper, to follow along. Nominated for 26 Emmys, FX’s gorgeous drama about power struggles in feudal Japan revolves around Lord Yoshii Toranaga (Emmy nominee and series producer Hiroyuki Sanada), a brilliant warlord seen as a threat by his fellow members on the Council of Regents. Toranaga’s rival regents conceive a plot to squeeze him out of the Council and consolidate their power. But Toranaga has an ace in the hole. His name is John Blackthorne (Cosmo Jarvis), an English anjin (or pilot) who has washed ashore in Japan. Blackthorne becomes Toranaga’s most valuable pawn in the ensuing game of three-dimensional chess.

On TV, as in life, politics is a full-contact sport that requires subterfuge.

The strategizing comes to a quietly operatic climax in Episode 8, “The Abyss of Life.” Toranaga has surrendered to his Council enemies and has accepted his fate. Or has he? His loyal cabinet, led by Toda Hiromatsu (Tokuma Nishioka), refuses to believe that their general has given in. Surely, this must be a ruse. Hiromatsu prepares to commit seppuku, or suicide by disembowelment, if Toranaga does indeed plan to surrender. Will Toranaga let his old friend kill himself in order to perpetuate what might be a carefully constructed stratagem? The scenario plays to the series’ greatest strength by wrapping a tense political struggle within purely human drama.

Meanwhile, Netflix’s “The Crown,” bowing out after six seasons with 18 nominations (and a total of 21 wins since its 2016 premiere), continues its smart dramatic study of competing public and private political image. The theme has been crucial since the series began, with the ascension of Queen Elizabeth II (two-time Emmy winner Claire Foy then; Emmy nominee Imelda Staunton now) to the throne. Season 6 focuses largely on the death of Princess Diana (Emmy nominee Elizabeth Debicki), but it also has its share of less lethal royal politics.

For instance, Prince Charles (Emmy nominee Dominic West) seeks his family’s approval of his fiancée, Camilla Parker Bowles (Olivia Williams), even as his retinue encourages him to publicly tarnish his ex-wife, Diana. Future Prime Minister Tony Blair (Bertie Carvel) tries to carve out his own slice of influence with the royals, a dynamic that goes all the way back to Season 1, when aging Prime Minister Winston Churchill (Emmy winner John Lithgow) sought to curry favor with both Elizabeth and her father, King George VI (Jared Harris).

This early Churchill storyline also touched on circumstances that should ring familiar in the U.S. in 2024: an elected leader facing foes who deem him too old to do his job. And it addressed a question that largely defines British politics, and that ran through the entire series: What is the role of an elected official in a society that cares first and foremost about its monarchy?

Finally, and closest to home: fear and loathing in America and in “Fellow Travelers.” The Showtime limited series, which picked up acting nominations for Matt Bomer and Jonathan Bailey, covers decades in the lives of its central characters. But its juiciest political battles are fought in the 1950s, at the height of McCarthyism, an era of brazen opportunism and fear-mongering that still permeates American electoral politics.

Based on the novel by Thomas Mallon, the eight-episode “Fellow Travelers” sets up shop at the intersection of the political and the personal, and asks if the two can ever really be separated. Hawk (Bomer) is an ambitious State Department employee who helps Tim (Bailey) get a job with his hero, Sen. Joseph McCarthy (Chris Bauer, under heavy prosthetics). They begin a tempestuous affair, marked largely by Hawk’s fierce desire to stay in the closet.

Tim, the gay conservative, is a romantic. Hawk, who leans left in his political alliances, is a careerist shark. They both live under a fact of ’50s life: To be out means to be cast out of public life. Later, they live under a dark shadow of ’80s life: the AIDS epidemic.

The public/private schism drives “Fellow Travelers,” which has its own personal connection to the current presidential race in McCarthy’s closeted henchman, Roy Cohn (Will Brill), a onetime mentor to Donald Trump who was disbarred in 1986. The series can be seen as a drama about the cost of selling one’s soul and whether redemption is possible after the transaction is completed.

Politics isn’t pretty in “Fellow Travelers,” which means it has a lot in common with the here and now. You enter the arena at your own risk. You might watch between your fingers. On TV, anyway, you have plenty of options.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.