Michael McClure, the poet whose roar helped launch the ’60s, dies at 87

- Share via

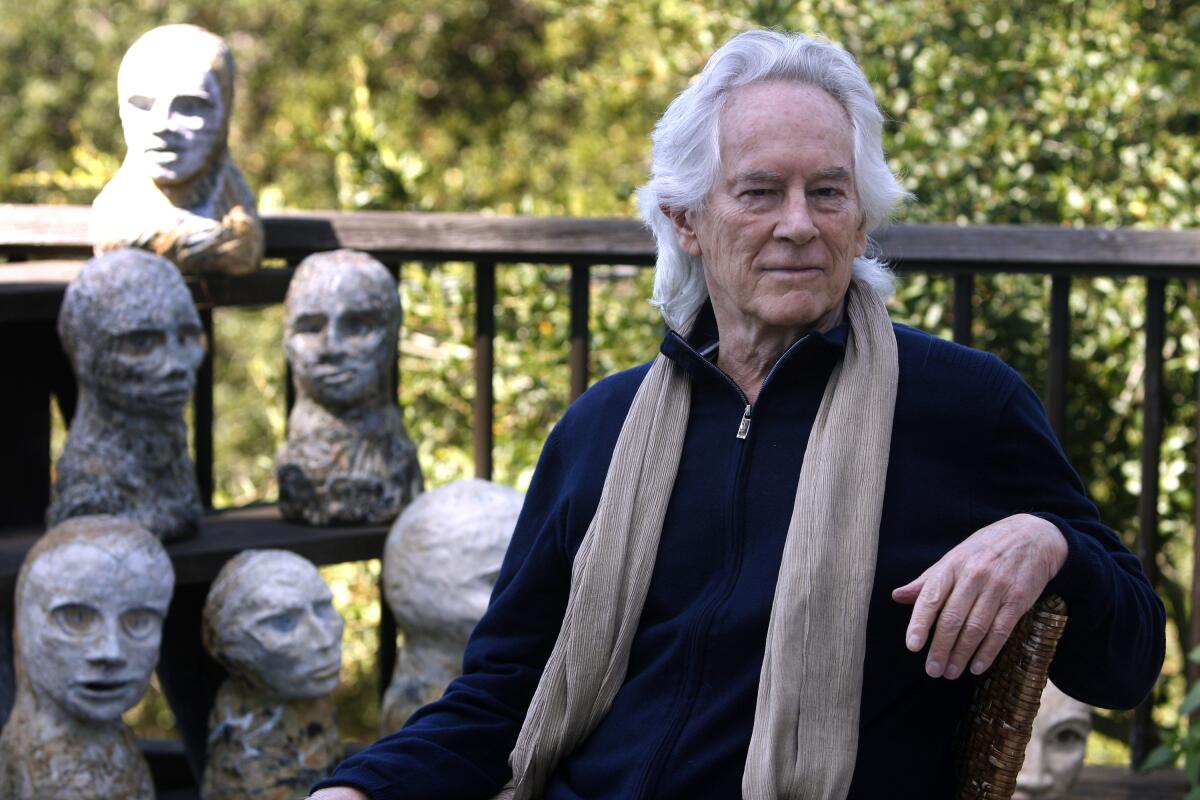

With his steely eyes and long, flowing hair, the poet Michael McClure somewhat resembled a lion, a creature with which he felt an affinity.

As he wrote in his 1963 poem “The Child,” “Who were the lion men with faces of fur / and manes / who bent by my crib to bless me?”

In 1966, McClure went so far as to read one of his poems to lions at the San Francisco Zoo. “Grahhr!” the free-spirited poet repeatedly roars at the beasts in a video documenting the event. He holds his book in one hand while another is stretched heavenward, not unlike a preacher’s. The lions roar back, though it’s unclear if McClure’s captive audience is more agitated than moved by the work.

McClure, who died May 4 at 87 after suffering a stroke last year, was a countercultural figure who was present, Zelig-like, at key moments in San Francisco’s Beat heyday and beyond.

As the late actor Dennis Hopper once said, “Without McClure’s roar there would have been no Sixties.”

A native of Kansas who found his true home in California, McClure mingled with actors and singers, not just writers. The Times once called him a “role model” for Jim Morrison. The poet also collaborated with Ray Manzarek, the late keyboardist for the Doors. With singers Janis Joplin and Bob Neuwirth, McClure wrote the song “Mercedes Benz,” in which Joplin sings, “Oh, Lord, won’t you buy me a Mercedes Benz? My friends all have Porsches; I must make amends.”

On screen, McClure appeared in Martin Scorsese’s seminal 1978 concert film “The Last Waltz” — perhaps the only rock documentary in which a poet reads lines by the Middle English author Geoffrey Chaucer. There were acting roles too: McClure played a Hell’s Angel in Norman Mailer’s “Beyond the Law” (1968) and had a cameo in Peter Fonda’s “The Hired Hand” (1971).

“He was so good-looking, he should have been a movie star instead of a poet,” Lawrence Ferlinghetti told The Times by phone. Ferlinghetti added that McClure’s death “was such a surprise because I always thought of him as being so young.” Ferlinghetti, the poet and co-founder of City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco, turned 101 in March.

Ferlinghetti said he met McClure in the 1950s, when the latter was in his early 20s. “He showed up from Wichita, with a couple of other poets from Wichita,” Ferlinghetti said. “And that’s the first I had ever heard of Wichita,” he added with a laugh.

On Oct. 7, 1955, McClure gave his first-ever poetry reading at the now-defunct Six Gallery in San Francisco. His fame grew because of another poet in attendance: It’s where Allen Ginsberg gave his first reading of his ground-breaking poem “Howl.” The last remaining living poet who read there is Gary Snyder, who turns 90 on May 8. Ferlinghetti attended, but didn’t read.

“I didn’t know Michael very well,” Ferlinghetti said. “He lived across the bay [in Oakland], so I had very little contact with Michael. He lived in another world.”

McClure had the good fortune, though, to be at City Lights in 1965 with Ginsberg and musicians Bob Dylan and Robbie Robertson. Black-and-white photographs of the gathering only added to McClure’s aura. This cool cat in a natty vest, cigarette in hand, was in the right place at the right time.

Ferlinghetti supported the Beats, publishing their works, including “Howl and Other Poems,” but he doesn’t consider himself a Beat poet. He said the same about McClure.

“He sort of joined the Beats,” Ferlinghetti said. “He felt an affinity with the Beat poets, but I really didn’t see it.” City Lights did publish McClure’s work, most recently “Mephistos and Other Poems” (2016). They also republished McClure’s 1964 collection “Ghost Tantras” in 2013. Ginsberg, in his singular phrasing, praised McClure’s work as “a blob of protoplasmic energy.”

A Buddhist, McClure experimented with poems that were self-conscious of the form itself. “My mind is fingers holding a pen,” he once wrote. His work was inspired, too, by the hills in Oakland where he hiked with his wife, the sculptor Amy Evans McClure. The poems helped fuel the eco-poetics movement, which addresses environmental concerns.

McClure was forever curious about other forms of writing, publishing essay collections, novels and plays. But he was a poet first.

“There is no way that you can read a poem by Michael McClure,” author Juvenal Acosta has said, “without experiencing some kind of connection with something primal and cosmic.”

McClure would have agreed.

“Poetry is a muscular principal,” said the man who incorporated lion roars into his lines. “There is no logic but sequences of feeling.”

McMurtrie is the former books editor of the San Francisco Chronicle.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.