For Jane Smiley in the year 2020, tough times call for furry tales

- Share via

On the Shelf

Perestroika in Paris

By Jane Smiley

Knopf: 288 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

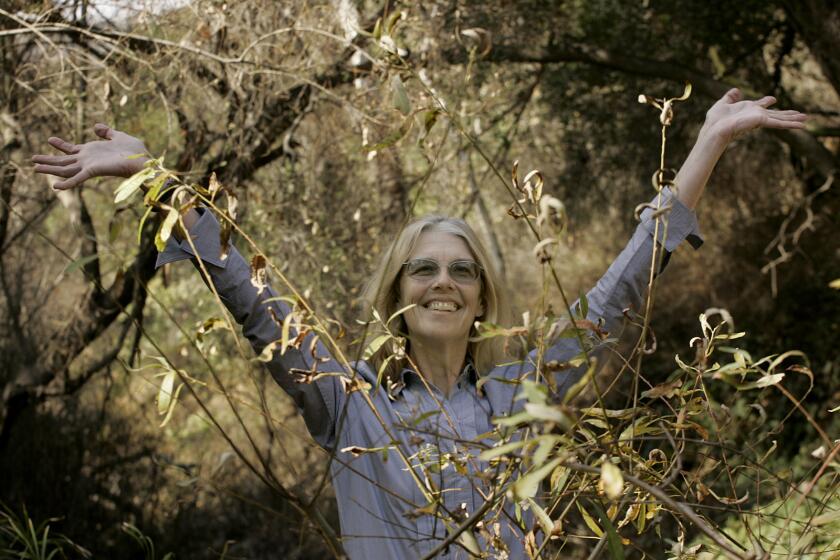

Jane Smiley earned a Pulitzer Prize for recasting “King Lear” as a modern tragedy on an Iowa farm and a National Book Award nomination for “Some Luck,” the first book in a century-spanning American trilogy. In other words, Smiley is a serious writer. But she doesn’t take herself too seriously as a person. She laughs frequently and heartily as she shares stories of life chez Smiley.

“I used to sit and strum my banjo, which I don’t do very well, and my Jack Russell terrier would come running in and start barking and then do a little howling,” Smiley says on a phone call from Carmel Valley, where she relocated in 1996 after many years in Iowa. “My German short-haired pointer, who was incredibly graceful and lovely but would lay on the couch and look like she was in despair, would then stare at me from across the room and join in with the most beautiful howl.”

This anecdote clarifies the inspiration for a German short-haired pointer named Frida, one of two heroines in Smiley’s latest book, “Perestroika in Paris.” The novel has nothing to do with the Soviet thaw of the late ’80s; it is built instead on the unlikely friendship between Frida and a racehorse named Perestroika.

Smiley, who has ridden horses since childhood, writes about them frequently in essays, novels like “Horse Heaven” and young adult books like “The Georges and the Jewels.”

What makes this book unique, though, is that while “Perestroika” has several important human characters — most notably a young, lonely boy named Etienne who befriends the horse (nicknamed Paras) — Smiley mostly writes from inside the animal’s minds:: Frida and Perestroika; a raven named Raoul; a mallard couple named Sid and Nancy; and a young rat named Kurt.

Over the last three months, 17 writers provided diaries to the Times of their days in isolation, followed by weeks of protest. This is their story.

While Smiley has spoken publicly of her disdain for the outgoing president and his party, the book is no “Animal Farm”-style allegory. In fact, it is wholly apolitical. In an era beset by polarization and even violent tribalism, it feels like a gift to find a novel in which characters of different species — with different desires and instincts — come together to build a community.

“It feels like a good time to be thinking about the things in this book, about kindness and trying to get by,” Smiley says.

Her Hollywood agent cautioned Smiley that the absence of a villain would kill any possible film deals. “But I didn’t want a bad guy in it,” she says. “Instead, there are real issues, for the boy and the horse and dog, about their future.”

“Perestroika” was conceived in a more hopeful year, 2009, but Smiley was unsure about writing from the animals’ perspectives. She focused instead on her trilogy, which concluded with “Golden Age” in 2015. But when she eventually returned to “Perestroika,” her husband, who gives daily feedback on her writing, “totally adored” it. “So I went to my publisher and said, ‘This might be a good one to distract people from the you-know-what-else is going on.’”

The novel gets going when Paras’ curiosity prompts her to nudge an unlocked gate and wander off. Her explorations land her in a park within sight of the Eiffel Tower, where Frida takes the horse under her wing, so to speak. Frida’s owner, a nomadic busker, died, leaving her forlorn; unlike a horse, a dog craves friendship. Frida shows Paras how to stay hidden from most humans and uses her street savvy to help keep Paras fed. The shopkeepers with whom they interact are, like Etienne, completely oblivious of the creatures’ complex inner lives.

“I wanted the animals to communicate, and the one I most wanted to fit in was the rat,” Smiley says. “Rats, as the rat knows, have a bad rap, but the more you learn about them the more interesting they are. I hope people empathize with the rat.”

This unusual tale is Smiley’s 32nd book and her 22nd since 2000. She traces the variety and volume of her work to an early passion for books. “I had a flashlight and would read under the covers and loved the sense of private engagement with the book,” she says.

Jane Smiley is an author who doesn’t shy away from ambitious literary projects.

In eighth grade, Smiley began taking Latin, which sparked an interest in its affect on English through Norman French; by the time she was at Vassar, she was fascinated by Old English, and in graduate school at the University of Iowa she studied Old Norse.

Her mother was another important influence; after divorcing Smiley’s father when Smiley was 2, she became a newspaper reporter. “She was an example, someone who has a typewriter on the dining table and has deadlines and bangs out the story she has to write,” Smiley says.

And then there’s Diet Coke, the final key to her prolific pace. “About three years ago I said, ‘It’s time to quit. I don’t drink coffee, but I just decided to deal with it. I tried all kinds of tea but they didn’t work. It wasn’t that I didn’t have any energy, it’s that I felt like I was in a state of existential despair ... which immediately went away as soon as I drank another Diet Coke.”

At UC Riverside, Smiley teaches a pragmatic approach to writing. The goal is to be wholly nonjudgmental on the first draft. “I’m not someone who writes lots and lots of words per day. Usually it’s about 1,000 or 1,200,” she says. “I’m going slow enough to pay attention but going fast enough to have energy.” After that, it’s time to turn on “your reader brain” and edit.

Smiley sees each novel as a different kind of puzzle. With “A Thousand Acres,” she mapped out the story to adhere as closely as possible to “King Lear,” but in writing her academia satire “Moo” she followed the story where it went — while maintaining a grid to keep track of her sprawling cast. “When I felt a character was getting lost I’d have a party, and bring them all back in.”

For “Perestroika in Paris,” Smiley wanted to let the animals’ story roam free, but she couldn’t entirely ignore the humans. “I asked myself if a horse could go unnoticed in Paris, and that brought up Pierre, the grounds manager, and then I had to give him a point of view and that led to Etienne. And then in winter, the horse had to have something to eat, so I added the baker, Anais, who feeds him.”

The 25th Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, Stories & Ideas kicks off this weekend. Due to the pandemic, this year’s series of free events will be virtual. Here’s everything you need to know about how to tune in.

In subsequent drafts, she also addressed her editor’s note about Etienne’s uncertain future by deepening the character of his great-grandmother, who frets about whether she is doing right by him. Still, the novel ultimately rides on Frida and, especially, Paras.

Smiley sees horses not only as a deep inspiration for her writing, but also a conduit for sharpening people’s empathy. “Riding horses, especially thoroughbreds, you have to try to sense the energy in their body, what they like or don’t like,” she says. “You have to understand the world as they are seeing it.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.