A new look at a Watts uprising report shows what we haven’t learned about racism in America

- Share via

On the Shelf

The Essential Kerner Commission Report

Edited by Jelani Cobb and Matthew Guariglia

Liveright: 320 pages, $18

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

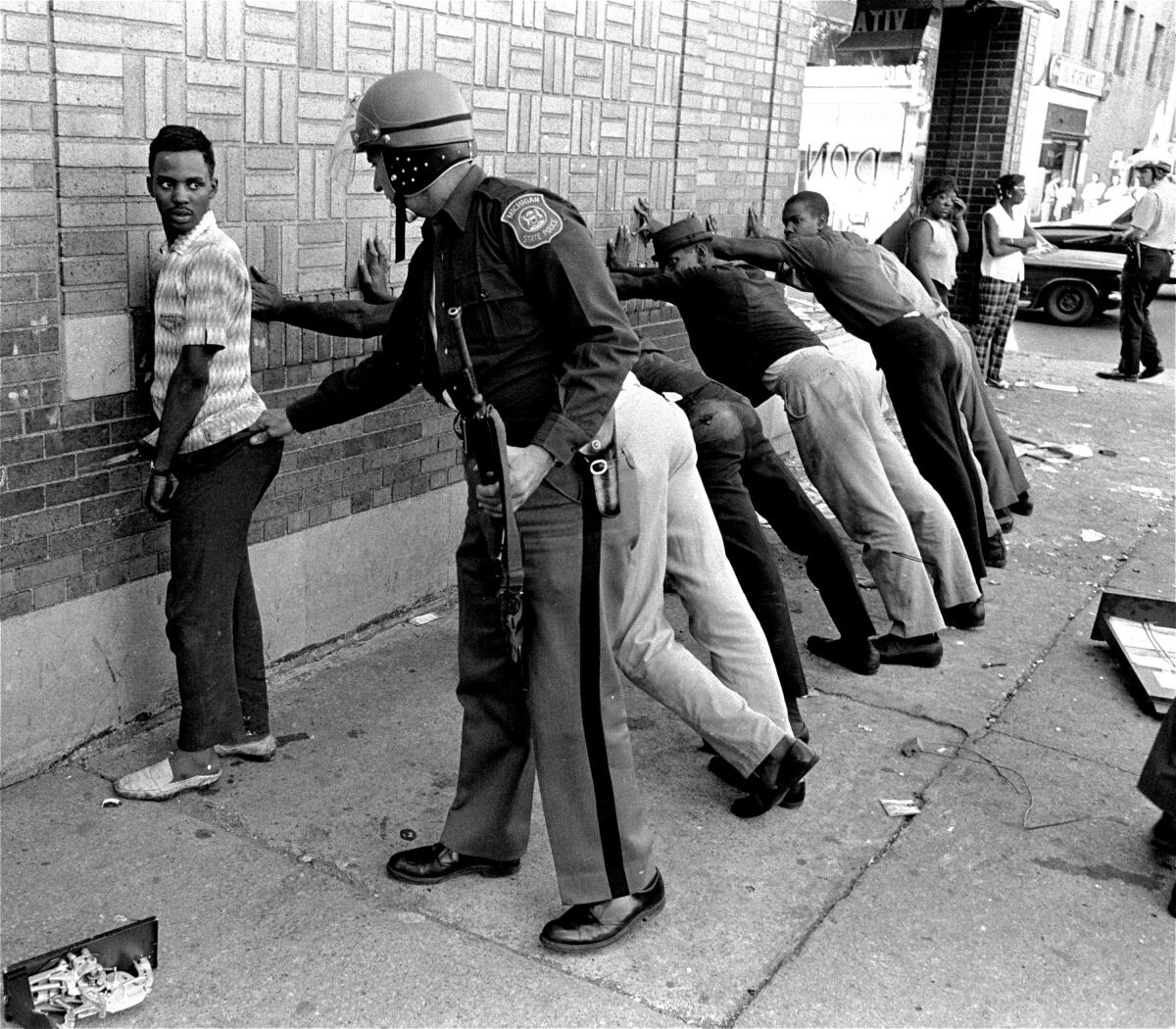

On the evening of Aug. 11, 1965, five days after then-President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act, police in Los Angeles pulled over 21-year-old Marquette Frye on suspicion of reckless driving. In the ensuing argument, the white police struck Frye in view of residents, who responded by throwing things at the officers. The confrontation metastasized into six days of civil unrest that left 34 people dead and large swaths of South L.A. in ruins.

In response to what happened in Watts and dozens of other disturbances between 1964 and 1967, LBJ formed the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders — popularly known as the Kerner Commission after its chairman, Illinois Gov. Otto Kerner Jr. — to examine what happened and why and to figure out how to prevent it from recurring.

In the 53 years since the Kerner Commission issued its report, awareness of its findings has ebbed and flowed in the public consciousness. At times, it’s been treated as something of a Rosetta Stone in the debate about race in America — especially since the 50th anniversary of its publication in 2018 and after George Floyd’s murder last year.

The opening sentence has endured: “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal.” But the 440-page report is hard to digest; what’s always been missing is a concise version. This week, New Yorker writer Jelani Cobb and UC Berkeley historian Matthew Guariglia publish what they hope is the Goldilocks edit (not too long or short), “The Essential Kerner Commission Report.”

Walter Mosley, Luis Rodriguez, the coiner of #BlackLivesMatter and others sketch a hopeful future for L.A. and the U.S. after George Floyd protests.

In a brisk introduction, the pair make the case for the report as a landmark document in American history, placing it alongside the more widely read findings of the Warren and 9/11 commissions. What distinguishes Kerner — and in their minds makes it so important — is that it’s more than a postmortem on a single tragedy like President John F. Kennedy’s assassination or Al Qaeda’s atrocity; it tackles the root causes of a persistent social ill.

Cobb and Guariglia situate Kerner in the broad sweep of post-World War II America, smartly positioning it as the apex of an evolving racial liberalism that began with Gunnar Myrdal‘s seminal study, “An American Dilemma,” which strongly influenced its thinking. Myrdal brought into the mainstream the idea that the “Negro problem” was really a problem of white racism, while contrasting it with the “American Creed,” a set of values like democracy, opportunity and fairness. In a broad sense, the civil-rights movement was an attempt to resolve Myrdal’s “dilemma” by highlighting the gap between the creed and racial reality.

The editors make the case that the Kerner report should stand alongside the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, the War on Poverty and the Fair Housing Act as “cornerstones” of 1960s liberalism. In many ways, as they note, the last half-century has been a long retreat from those ideas. But their key point is that police abuses like Floyd’s murder are the inevitable result of failing to act on the commission’s recommendations: Our problems are born not of ignorance but of a lack of will. Reworking the famous Santayana quote, they write, “Kerner establishes that it is possible for us to be entirely cognizant of history and repeat it anyway.”

The report itself remains remarkably salient and readable. Cobb’s and Guaraglia’s edits draw attention to misconceptions regarding the key players in civil unrest then and now: police, protestors and the media. On policing, the report does a great job of detailing how police-community confrontations were “merely a spark” inciting unrest by embedding officer misconduct within larger structural inequalities — segregated neighborhoods, substandard housing and low-paying (or no) jobs.

Howard University students and faculty welcome Nikole Hannah-Jones, believing she will benefit both the university and the journalism she fights for.

The findings destigmatize the protestors and their grievances. In the white imagination, participants were stereotyped as criminals and the “uneducated underclass” and their actions as nihilistic and antiwhite. But in truth, while the majority of those categorized as “rioters” were Black males in their late teens to early 20s, in other ways they betrayed stereotypes. They were slightly better educated and more politically engaged than their peers; they were also more likely to live in the most crowded, segregated and impoverished neighborhoods. And they were focused on substantive issues. According to the commission, their three “first level” grievances were police practices, lack of good jobs and inadequate housing.

“The Essential Kerner Commission Report” also puts renewed focus on the media. The criticisms are familiar today: not enough diversity in journalism, an overemphasis on the drama of the moment versus an understanding of the underlying causes and a tendency to cover certain neighborhoods only when they are on fire. While reinforcing the connection between systemic inequality and civil unrest, this section of the report shows why the press had failed at that very task.

Although the edits are helpful, the editors could have been more transparent about their process. They are vague on their reasoning: “We have judiciously trimmed the material here to retain the most vital of these suggestions and excise those that are overly specific… repetitive or… less immediately pertinent to contemporary readers.”

There are some interesting choices that would have benefitted from more explanation. For example, given the recent debates about the 1619 Project and how the history of race is taught in schools, why omit the chapter on the history of race and protest going all the way back to the founding?

A Q&A section at the end fills in some gaps about what happened after the report’s release: Why didn’t Black residents just move out of blighted neighborhoods? Did the report discuss defunding the police? Has there been progress since it came out? This chapter is too short. I wouldn’t have complained if both the introduction and the Q&A were half again as long, providing just a bit more context.

Annette Gordon-Reed, Ayad Akhtar, Héctor Tobar, Martha Minow, David Kaye and Jonathan Rauch discuss the Jan. 6 riot and what we do about it.

In grad school, my mentor, the late, great Joe Miller, used to say that any really good title had to work on multiple levels. Cobb and Guariglia fulfill that directive with one word. This book is essential in the sense of containing the fundamental parts. But it is also essential in the sense of being an extremely important, even necessary, read. At a moment when the facts of history themselves are being undermined, when the Supreme Court has deemed civil-rights protection no longer necessary and the myth of white innocence has gained renewed traction, the Kerner Commission Report remains essential reading — discouragingly so.

Lewis is the author of “The Shadows of Youth: The Remarkable Journey of the Civil Rights Generation,” among other books.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.