John Darnielle: musician, novelist, ethicist of the lurid

- Share via

On the Shelf

Devil House

By John Darnielle

MCD/FSG: 416 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Depending on how you measure it, the roots of John Darnielle’s third novel, “Devil House,” date back to 2004, the ’80s era of Satanic panic or the late 14th century.

The book’s main narrator, Gage, is a true-crime author who’s headed to the Bay Area for a feat of stunt reportage: He’s working on a book about a 1986 double murder in an abandoned porn shop, and he’s purchased the property to better capture its aura. That’s where 2004 comes in: It’s when Darnielle, the novelist and frontman for indie rock group the Mountain Goats, spotted a ramshackle porn shop in his current hometown of Durham, N.C. Homemade sign, vaguely creepy name: Monster XXX. When the building was demolished a few years later, he got to thinking about disappeared pasts and lost stories.

“You could put a lot of life [as a novelist] into an edifice whose existence can no longer even be demonstrated,” Darnielle says via phone from Durham. “The germ of the book was having driven past a weird porn store that looked like somebody’s hobby.”

The novel shifts this milieu to Milpitas in Silicon Valley; the store becomes the abandoned Adult Monster X, which is commandeered by a group of teens who turn its stockpile of smut into an epic art project. When the building’s owner and potential buyer are murdered onsite, gossip circulates around pentagrams, occult rituals and wayward teens. The book also takes a detour to San Luis Obispo, where Gage wrote about a wrongly convicted high school teacher who defended herself against a robbery by two of her students. Both cases circle a running theme: panicked and spurious stories that get youth culture very wrong.

Darnielle spent part of his childhood in both cities, and the novel continues his fixation on the ’70s and ’80s culture he grew up with. His debut novel, the National Book Award-longlisted “Wolf in White Van” (2014), turned on a correspondence role-playing game, and “Universal Harvester” (2017) was set in an old-school video store. His intention throughout his work is not so much to indulge in “Stranger Things”-style nostalgia, he says, as it is to capture the moment in our lives when we see the world cleanly.

When the longlist for the National Book Awards was announced last week, it had the usual suspects – books by previous winner Richard Powers and two Pulitzer winners, Jane Smiley and Marilynne Robinson.

“When I go digging for images, I’m looking for the time when those images had the most newness for me,” he says. “So the ’70s and ’80s are usually going to be where I’m digging for reference points.”

It was during his California childhood that he began watching the splatter films that fuel much of “Devil House” — abuse and dismemberment play not-small roles in the story. “Devil House” can be read as the psychic runoff from that experience, equal parts attraction and repulsion. “I didn’t want to have a collection of true-crime books, but I couldn’t resist finding out about the lurid details,” he says. “I was Catholic until my family divorced, so I have a little of that ‘Be attracted to this thing that will make you later feel ashamed’ in me. But I’d ask, what am I accomplishing for myself by drowning myself in this stuff?”

Gage too wrestles with that question, so Darnielle gets to have it both ways: “Devil House” has all the gross-out hallmarks of horror and true crime while also questioning the moral implications of the genres. Along the way, the book takes another byway into Arthurian legend, the better to explore Gage’s weakening grip on the line between myth and reality.

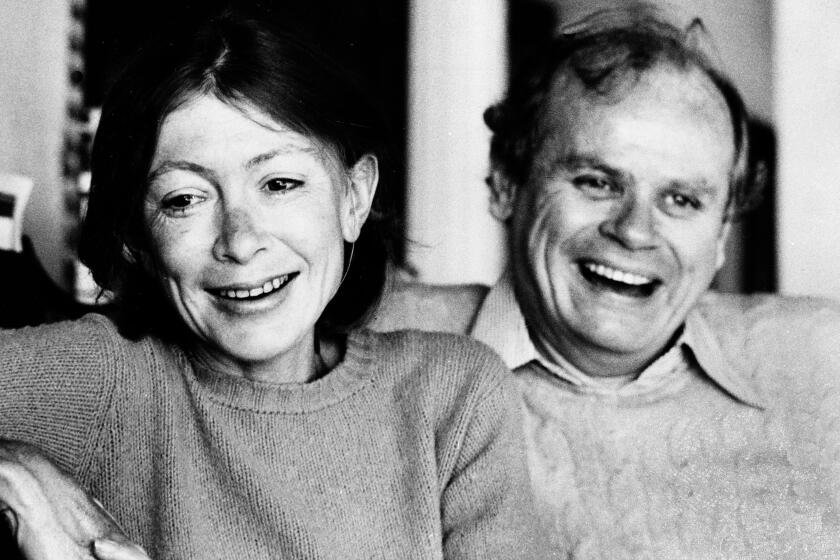

Darnielle, like Gage, is obsessive enough about the topic that he says he spent an inordinate amount of time arriving at the right font for a section set in Ye Olde Times. (He takes a moment to look it up: Claudius.) But he’s obsessive about literature in general — perhaps no surprise to those who know him from his highly literate songwriting for the Mountain Goats. In conversation, he enthuses about a stack of recent works in translation, including Croatian author Miljenko Jergovic’s 1,000-page epic, “Kin,” and explains his college thesis on Joan Didion, which he then ably connects to “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.” (“My theory was that ‘Play It as It Lays’ is a work of tragedy. … A real tragedy involves something terrible striking somebody who could have seen it coming had he known how to read the signs.”)

As an undergraduate at Pitzer College in Claremont, Darnielle studied “The Canterbury Tales”; his new novel is dedicated to the professor who taught it, Barry Sanders. “It changed my life — his Chaucer course was absolutely the most illuminating thing for me,” Darnielle says.

The admiration is mutual. Sanders, a literary scholar, retired from Pitzer in 2005 and now is the founding executive co-director of the Oregon Institute for Creative Research. He recalls Darnielle as one of his strongest students.

“John took to ‘The Canterbury Tales’ like no other student I’ve ever had,” he says. “He had one foot in the 14th century and another in the 20th century. It delighted him. I think he was keeping notes before that, but that’s when he really began in earnest to write music and prose and poetry. One could see immediately that he had a gift.”

Joan Didion, who died Thursday, left a seismic impact on the literary world and her home state of California.

“Devil House” arrives on the heels of a peculiar moment in Darnielle’s career: Last fall TikTok users en masse began posting videos of dances to “No Children,” a sardonic breakup song the Mountain Goats released in 2002. For a flicker of a moment, Darnielle (or at least the song) was famous-famous, not just indie-rock-famous, and the group launched a tongue-in-cheek (and ultimately failed) campaign to replace a COVID-quarantined Ed Sheeran on “Saturday Night Live.” But Darnielle was loath to do much more than observe his viral moment bemusedly. No special run of T-shirts. No TikTok dance of his own.

“I have some fairly antiquated ideas about propriety,” he says. “It would’ve taken the fun out of something that was literally 100% organic.”

As with TikTok, so with novels. Running through “Devil House” is a dilemma that was always on the author’s mind as he wrote it: What gets shared with the public — whether true crime or viral moments or lurid horror novels — always runs the risk of exploitation.

“If a book says ‘Devil House’ on the cover, you should be ready for some violence,” he says. “I don’t want to go so far as to say people shouldn’t write things that will bother people. That’s fine. But I do think that if we’re telling stories,” it never hurts to ask, “What will the effect of having told this story be? Who might suffer if I tell a story?”

“Devil House” delivers the pleasures of a good horror novel. But it bears the weight of those questions too.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

From ‘Unsolved Mysteries’ to ‘I’ll Be Gone in the Dark,’ true crime is ubiquitous on TV. But it may not be as impactful as its cultural footprint suggests.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.