Andrew Holleran should be a giant of queer literature. His new novel on aging proves it

- Share via

On the Shelf

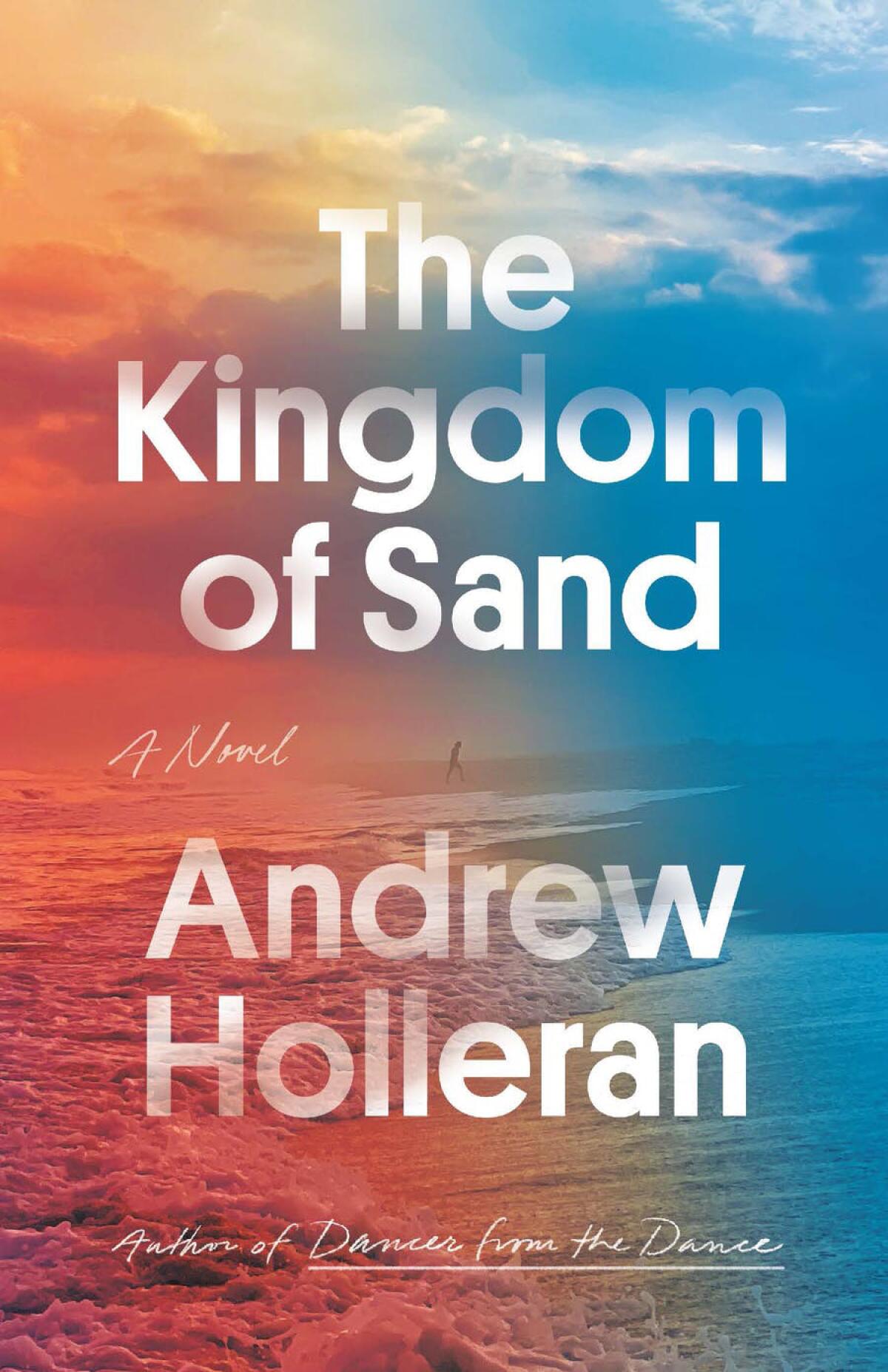

The Kingdom of Sand

By Andrew Holleran

FSG: 272 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Andrew Holleran’s fifth novel, “The Kingdom of Sand,” announces its theme early. “This story is about the things we accumulate during a lifetime but cannot bear to part with before we die,” its unnamed narrator explains. Which is to say that it continues the project Holleran began four decades ago: elegant, contemplative works obsessed with matters of intimacy and loss.

Holleran’s debut, 1978’s “Dancer From the Dance,” is among the great post-Stonewall novels, capturing the fading youth of a coterie of gay New York men. His 2006 novel, “Grief,” is a melancholy masterpiece about how so many of those men were cut down by AIDS. His essays and other works of fiction are similarly rooted in the lives of gay men, but his Jamesian powers of observation haven’t translated into major prizes or name recognition. Blame the long waits between books, or a mainstream literary culture that’s often treated LGBTQ fiction as a niche enterprise. Regardless, a Library of America volume would be the least he deserves.

Paul Lisicky’s memoir “Later” encapsulates a quarter-century of queer life

In such a collection, “Sand” would feel like a summation of Holleran’s work, circling tighter than ever around matters of desire and mortality. The narrator has experienced plenty of loss: Living in north central Florida, he catalogs the deaths of his parents, his friends and perhaps his nearing own. While he’s still healthy, he staves off the inevitable by trying too hard — proving his virility by consuming porn and cruising a local boat ramp and video store, hoping for connection. Yet he’s realizing that his pursuits don’t deliver the validation he craves, that there’s little joy in chasing “the same quintet of egg-shaped men in baggy T-shirts.”

That feeling is underscored by the narrator’s friendship with Earl, a man about 20 years his senior. They first met at the boat ramp when the narrator was in his early 40s, and though there was no romantic or erotic spark, they’re content with their casual, platonic relationship. The narrator simply swings by Earl’s to make small talk and watch movies. But if their friendship is cozy, Holleran also makes it slightly funereal. Earl’s home is an airless, tidily ordered sanctum of records and movies fussily cataloged on index cards. “As long as I went there, I never saw Earl once open the vertical blinds that covered the sliding glass doors that led outside. It was as if Nature did not exist; only Art.”

A world filled with art but no nature is, well, unnatural. And Holleran slowly gives the relationship an increasingly otherworldly, creepy vibe. One of Earl’s bathrooms is closed because it’s constantly attracting cockroaches. Earl is quiet and diffident, except to express surprisingly right-wing politics. The increasing presence of a handyman raises suspicions. The titles of their classic movie selections grow darkly suggestive: “Quo Vadis,” “Psycho,” “I Want to Live!”

The tension in the two men’s “shared loneliness together” has little to do with plot — it’s clear from the start that everybody is headed in one direction, underground. Rather, the suspense is over how — and whether — the narrator is going to confront his and Earl’s mortality. The narrator has lost both his parents and left most of his close friendships behind in New York; he clings to Earl out of a fear of intimacy he only half-acknowledges. “It seemed to me that [Earl] had buried himself alive like the man in the story by Edgar Allan Poe,” he writes, oblivious to the shovel in his own hands.

Our regularly updating 2022 Pride guide to culture will feature novels and memoirs from LGBTQ icons, must-see TV series, music, movies and much more.

“The Kingdom of Sand” isn’t persistently mordant, but its humor is inevitably of the black-comic sort. “You have to let people in your life. Someone has to pick you up after your colonoscopy!” one lunch-friend implores. “When Life is behind you, you can eat whatever you want because you’re on your way out,” the narrator notes. He inverts the opening of “Pride and Prejudice,” creating a sharp joke of it: “It is a fact seldom observed that after a certain age a single man is a creature no one has any place for.”

It’s rare to find fiction that takes this kind of dying of the light as its subject and doesn’t make its heroes feel either pathetic or polished with a gleam of false dignity. Philip Roth’s 2006 novel, “Everyman” — with its classic line, “old age isn’t a battle, it’s a massacre” — gets closest to the mood Holleran is trying to capture.

Aging, frailty and death are universal themes. But Holleran also understands them as particular to a culture trained on (as the title of his 1995 novel put it) the beauty of men. “The cliche that homosexuals are such aesthetes that images of old age tend to horrify them is not entirely untrue,” the narrator observes. “How else do we explain the age segregation in gay bars?” Toward the novel’s end, the narrator cruises a Walgreens with relentless, eager eyes — what other place keeps nightclub hours in a town like this, for a man like him?

Is it poignant or pathetic to be in that predicament? Are options foreclosed on him by society — especially a retrograde Florida town — or did the narrator cut off options all on his own? Holleran, like his narrator, dwells less on causes than feelings — impending death as a sensory experience. At one point, he finds an exquisite metaphor for it in a fireworks display. The losses, like the spectacle’s first explosions, come slowly at first, then relentlessly, culminating “in a sort of orgasm—and then, when the individual flames had spiraled down to the earth and there was nothing but wisps of smoke riding into the air, the darkness you get only in a small town in the country would return.” This sad, beautiful book captures the sensations Holleran’s characters are chasing — as well as the darkness that inevitably comes for them, and us.

Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller on their podcast and book, “Bad Gays,” and rethinking queer history through the lens of imperfect people.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.