What’s democracy’s greatest threat? One historian has a clear answer

- Share via

On the Shelf

One Person, One Vote: A Surprising History of Gerrymandering in America

By Nick Seabrook

Pantheon: 384 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

There are so many things wrong with our political system: the electoral college, lifetime appointments for Supreme Court justices, the ambiguous wording of certain constitutional amendments. But Nick Seabrook’s “One Person, One Vote” argues that many of America’s problems stem from one eternally timely issue.

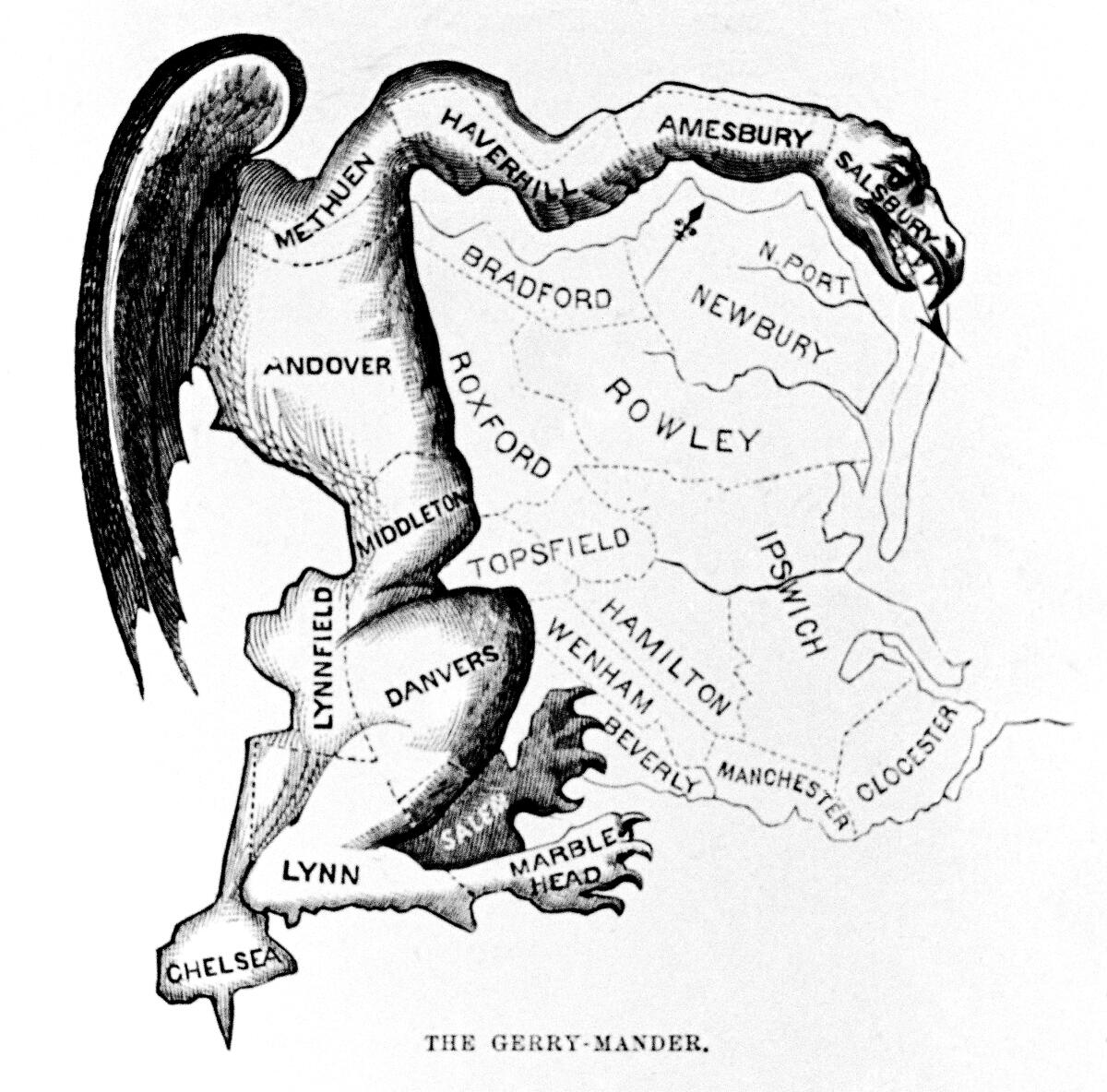

Gerrymandering involves the redrawing of congressional, state and local districts for political gain. It’s done by both sides and has often been used to sideline minority representation, especially in the aftermath of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that removed obstacles that had long prevented Black people from voting in the South.

Seabrook’s title refers to a series of 1960s Supreme Court decisions that required every district to contain roughly the same number of people. But it’s also an ironic title because the increasingly sophisticated process works around that requirement, stretching and squeezing districts to predetermine outcomes and making votes count for less and less.

“The number of competitive seats has been declining every decade and is now at its lowest point in probably a hundred years,” Seabrook, a professor at the University of North Florida, said during a recent video chat. Moving forward, the conservative-majority Supreme Court seems set to allow further distortions of the map as states engage in furious lawsuits to settle a new round of redistricting.

In our conversation, Seabrook made clear that practical solutions exist but achievable ones are in short supply. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Annette Gordon-Reed, Ayad Akhtar, Héctor Tobar, Martha Minow, David Kaye and Jonathan Rauch discuss the Jan. 6 riot and what we do about it.

Gun control is just the latest source of frustration with government inaction. Republican members of Congress in safe, gerrymandered districts worry only about being primaried from the right. Is that an additional obstacle to sensible reform?

Yes, but it’s not just gun control. Gerrymandering has magnified the divide between parties and contributes to the disappearance of centrists. So we’re starting to see the likes of Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Boebert winning elections and being secure enough in their seats to do the kinds of things they’ve done. They’re obviously outliers, but they’re indicative of a broader trend. It’s manifested on both sides, but the Republicans are more extreme. It’s only likely to get worse looking in the latest cycle emerging from redistricting. [Districts are redrawn based on a new census at the beginning of every decade.]

Both parties gerrymander. Are the Republicans more willing to discard democratic norms or just better at the process?

I don’t think the Republican Party has been more devious or underhanded, they’ve just had better fortune and timing. They came into power in the 2010 election, winning control of state legislatures right when the technology was there to much more accurately forecast how districts would perform in the future. Now these gerrymanders hold up for an entire decade.

There’s a sense that Democrats have been unilaterally disarming. In California, with Proposition 11, a lot of powerful Democrats — Nancy Pelosi and others — opposed the creation of that commission. Otherwise, imagine how far the Democrats could go in gerrymandering the 55 congressional districts. California alone might have been sufficient to wipe out all other Republican gains.

What to you are most egregious current examples of gerrymandering?

The two worst at the national level are Florida and Texas. They had one bite at the apple in 2010 and learned from that experience. With the new technology, people packed their opponents into a few supermajority seats and made the rest more competitive to maximize the number that your side wins. But what they’ve realized is that if you push things too far you can end up creating too many competitive seats and it’s better to shore up the seats you already hold.

State politics is often overlooked. Is gerrymandering worse there or are we just not paying attention?

It’s both. I wish the national media would pay more attention to gerrymandering of state legislatures. We pay a lot of attention to Congress, but while the GOP may gain seats from gerrymandering in Florida and Texas, the Democrats can do it in Illinois, so it cancels out a bit. But at the state level that’s not the case.

Look at Wisconsin — their [Republicans’] margin in the state legislature has barely dipped below two-thirds since 2010 despite elections where the Democrats won the popular vote overall. So that’s worse in terms of its anti-democratic implications. You have entire state governments uncompetitive for a decade.

Democrats’ strategy to ignite a Senate debate on voting rights begins to wane after Sens. Sinema and Manchin reiterate opposition to changing filibuster rule.

You take the Supreme Court to task for not resolving gerrymandering beginning in the 1990s and use the term “cowardice” regarding Anthony Kennedy’s waffling. Do the specifics of gerrymandering lawsuits matter or are we beholden to the whims of the justices?

Initially, with racial gerrymandering, facts did make a difference. There was stuff that was unbelievably egregious across the South — Alabama redrew the boundaries of Tuskegee to remove all but four African American residents from the city limits. There was a consensus that those things were unconstitutional, but that was the low-hanging fruit.

Then with “one person one vote” we saw more nuanced cases in the 1980s and things start diverging ideologically. Republicans start becoming a lot more skeptical that courts should intervene. In the 1990s we get into majority-minority districts and using redistricting for affirmative action and that’s more controversial.

I’m critical of the conservative majority on the court, but more for their hypocrisy than for the underlying merits of the cases. It’s fine to say redistricting should be race-neutral. But with partisan gerrymanders in the 1990s they’d throw up their hands and say, “It’s really complicated and I don’t know if we have appropriate standards for deciding this,” and on the very same day they’d hand down decisions for racial gerrymandering cases where they had a finely tuned, almost mystical sense of where [it] went too far.

Would open nonpartisan primaries using ranked voting eliminate some of the incentives to gerrymander?

It’s not a panacea, but ranked-choice voting is preferable. But ultimately, the gerrymandering problem won’t be fixed until we take the power away from politicians, as every other country has realized. Allowing political actors to draw the maps is too much temptation for them to resist.

Will politicians give up that power?

Even in red states like Utah and Ohio, when people get the opportunity to vote on initiatives or a referendum, they vote for reform. The problem is getting those questions on the ballot to begin with. But Congress could pass legislation for the House. The recent voting rights acts had reform in their bills, but they haven’t passed yet. If that happens then maybe some momentum starts to build. But it’s hard to get started.

Preferring substance over spectacle, real emotion over grandstanding, the first night of the Jan. 6 hearings successfully grabbed America’s attention.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.