The graphic memoir of an Apple Valley ‘Afro-Punk’ mirrors cross-racial journeys like mine

- Share via

On the Shelf

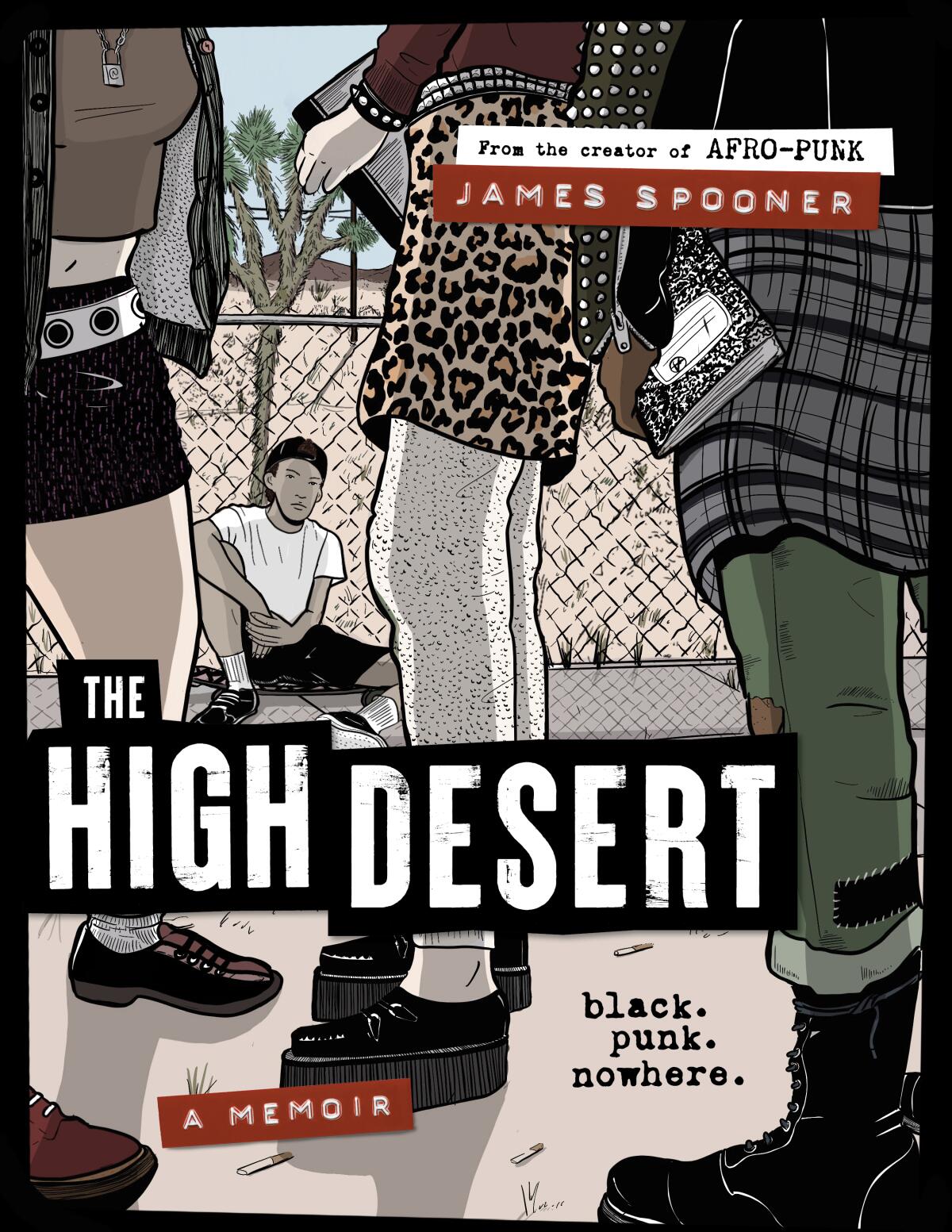

The High Desert: Black. Punk. Nowhere

By James Spooner

Harper: 368 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

There’s a poignantly vulnerable moment depicted in “The High Desert,” James Spooner’s memoir set in turn-of-the-‘80s Apple Valley, Calif. The author, a biracial high schooler who has embraced punk rock culture, is on the phone with his white pal, Melody.

“Would you ever date a Black guy?” the 16-year-old Spooner asks. Melody offers a muddled, evasive response (“You know I’m not like that … I mean, I’m taking a sabbatical from boys for a while”). Suspecting he’s been friend-zoned because of his race, Spooner makes a painful admission to himself:

“Sometimes I wish I was white.”

This awkward exchange gives you an idea of how deftly “The High Desert,” released in May, chronicles the complexities of life for Black teens growing up in mixed neighborhoods. Written and impressively illustrated by Spooner, the graphic memoir finds the author exploring the identity crisis that eventually inspired him to launch Afro-Punk, a sort of international arts collective for Black rockers. Initially earning acclaim for his 2003 documentary “Afro-Punk,” Spooner is perhaps most widely known as co-founder of the annual music festival under the same name.

Though Spooner’s memoir unfolds in a remote California town, “The High Desert” struck a deep personal chord for this former Hoosier. Much like Spooner, I swam against the tide of racial expectations in 1970s Indiana: a Black teen with a passion for white rock acts like Led Zeppelin, Queen and Yes. During a recent telephone interview, Spooner and I compared notes about our experiences. Though our journeys aren’t identical, we learned our stories share one crucial commonality — we both embraced white rock culture as a means of survival.

Alison Bechdel talks about her ‘fitness memoir,’ ‘The Secret to Superhuman Strength,’ the first book in 9 years from the pioneering graphic memoirist.

For my part, rock represented a subconscious attempt to stay sane while growing up in post-civil-rights-era Gary, Ind. For Spooner, white punk was a defensive strategy, a way of fitting into Apple Valley High while negotiating the town’s brutal white supremacists. “When I was a kid and I said I wanted to be white … ultimately, I was saying I don’t want to have the problems Black people have in this country,” Spooner said. “I wanted to be able to go to school without thinking about my race. I wanted my features to be seen as beautiful by the mainstream, meaning the white girls at my school.”

Like most coming-of-age books, “The High Desert” is the saga of a square peg. What differentiates Spooner’s memoir is its bold confrontation of race. The son of a Black St. Lucian bodybuilder and a white American mother, Spooner grew up as a fly in the buttermilk — slang for a Black person in a predominately white environment. Apple Valley’s teens — a motley mix of identikit “Normals,” progressive punks and racist skinheads — made Spooner resent his ambiguous looks. “At times, there was shame that I wanted to be white,” the author said, “other times there was the shame that I want to look Black.”

In hopes of appearing more threatening to his bigoted aggressors, Spooner adopted a punk image, trading his B-boy garb for a leather jacket and a mohawk — the default uniform of punks. Partial to hardcore bands, Spooner embraced the Sex Pistols’ anti-authoritarian diatribes and Minor Threat’s teetotaling, “straight edge” philosophy. And he declined to join a street gang, the path often taken by urban kids hoping to project instant, fearsome masculinity. “The way punks were portrayed in the media (in the 1980s) made them seem scary,” the author stated. “As annoying as it was having people put (punk) labels on me like ‘devil worshipper,’ it was definitely better than being called a n—.”

I had, in some ways, the polar-opposite experience. While Apple Valley forced Spooner to face the ugliness of white racism, Gary’s rapid downward spiral made me associate Black life with disunity and dysfunction. In 1967, when Richard Hatcher was elected Gary’s first Black mayor, panicked white people fled to the suburbs, quickly transforming a reasonably attractive city into an increasingly squalid hinterland split unevenly between slums and well-kept neighborhoods. As if this disintegration wasn’t heartbreaking enough, I was receiving routine beat-downs from thugs who viewed my patois-free speech and teacher’s pet stature as sucking up. A bully once beat me so bad, he opened a gaping wound on my mouth, as if to keep me from “talking white” ever again.

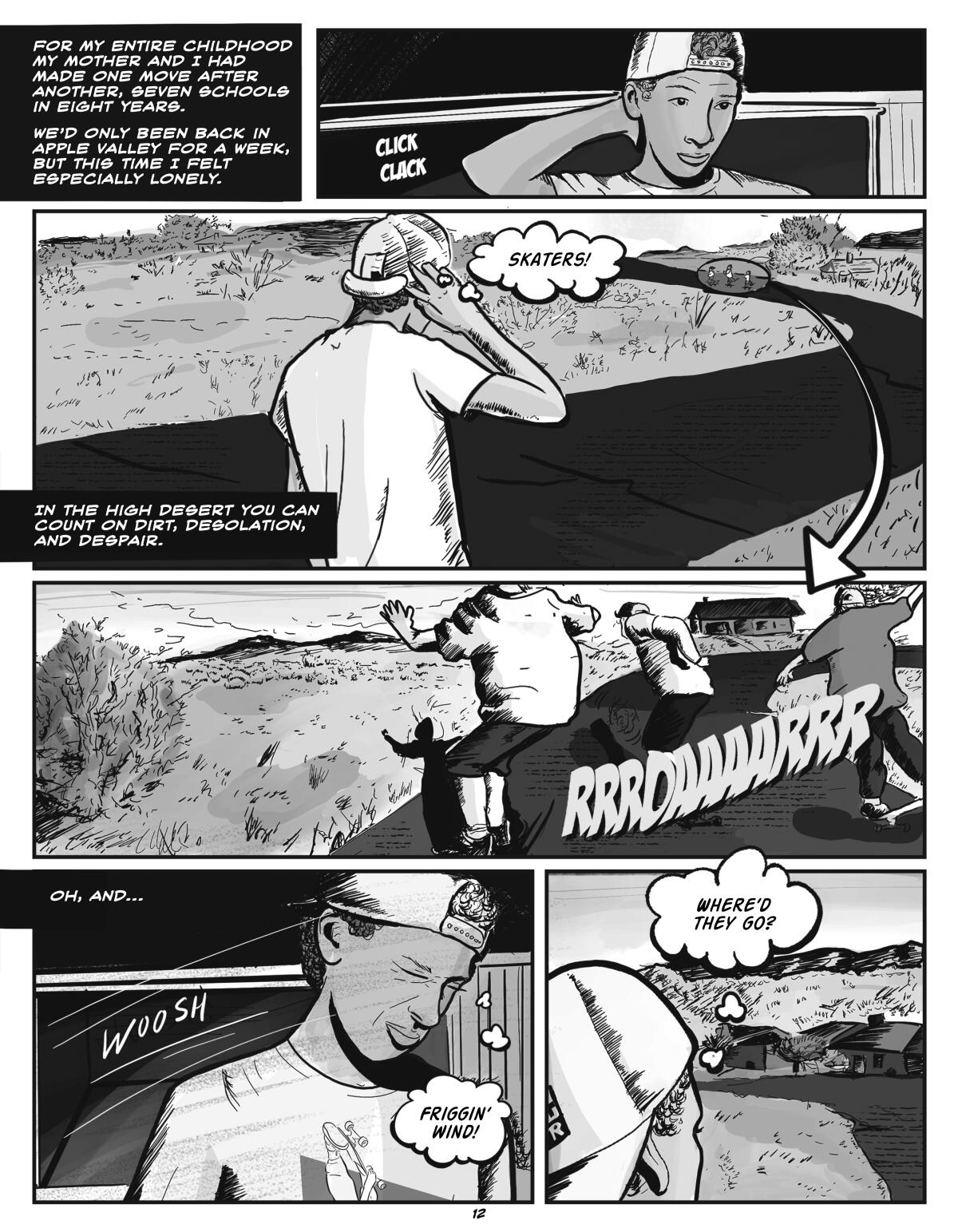

Such experiences can prompt ambivalent emotions toward one’s hometown. “I despise you ‘cause you’re filthy / but I love you ‘cause you’re home,” J.D. Loudermilk sings in the 1959 blues standard “Tobacco Road.” Like Loudermilk’s detested town, Spooner’s Apple Valley is depicted as a derelict wilderness (“in the high desert, you can count on dirt, desolation and despair,” he writes). The threat of sudden, remorseless racial violence hangs over Spooner’s memoir like a shroud. This high desert feels hot and barren — of water, vibrancy and, for Spooner, soul-slaking acceptance and human connection.

Standout looks from Afropunk in New York appeared to be inspired by Lil Nas X, HBO’s “Euphoria” and more.

His bitterness is a feeling I know well. As I saw Gary crumble, it never occurred to me that the city’s demise was partly attributable to prejudiced whites who made no attempt to work with their new Black mayor. All my naive eyes could see was Gary’s swift, horrifying descent, and I wanted out.

Gary’s metamorphosis occurred just as I was entering adolescence. As a kid, I enjoyed watching TV shows like “The Partridge Family” and “The Brady Bunch”— teen-oriented Hollywood fluff centered on impossibly earnest characters. Those shows portrayed the life I craved — safe, genial, goody-two-shoes. Even today I marvel at the oft-debated notion that white people have no culture, rooted in the belief that mainstream American phenomena like rock ‘n’ roll, dance music and modern slang are all appropriated from Black people. According to the conventional wisdom, real white culture — WASP-y amusements like golf, buffet dining and classical music — is comically bland.

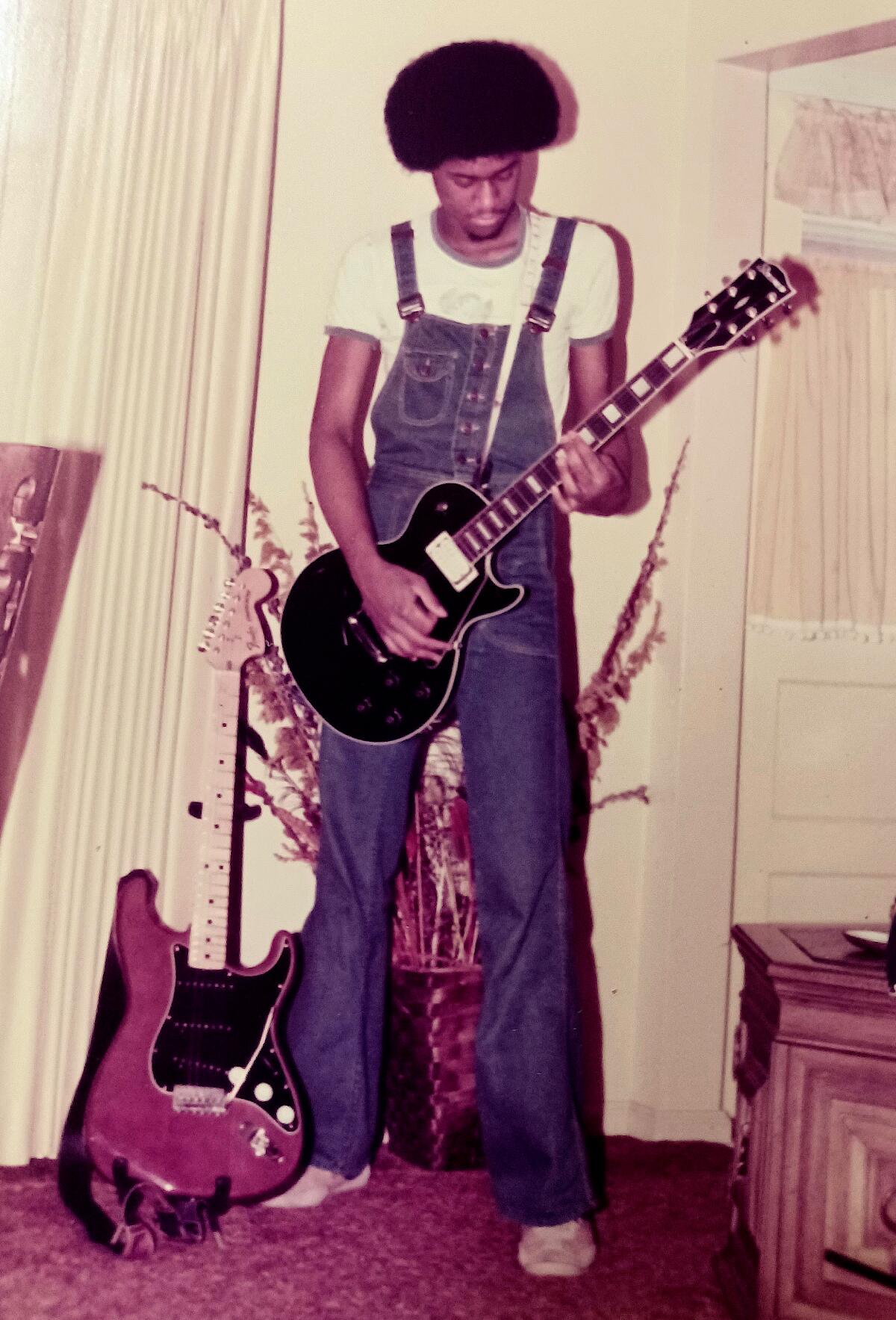

Maybe so, but to a sensitive Black kid rattled by urban life, bland not only seemed appealing; it was positively exotic. I cultivated a taste for the music of white suburbia. Not long after purchasing my first rock album — Grand Funk Railroad’s “E Pluribus Funk” — I quickly began relating as much to white bands like Pink Floyd and Bad Company as to the Jackson 5 and Stevie Wonder. Nights found me embarking on musical safaris into the white wild, tuning in to freeform radio station WXRT, whose playlist ranged from proto-metal and progressive rock to singer-songwriters and hippy-dip folkies like Bob Dylan and Arlo Guthrie. Rock transported me out of perishing Gary, allowing me to fantasize that I was living in the tranquil suburbs. But that yearning for serenity concealed a rage — against my Blackness.

Spooner too admits he lacked the maturity and experience to process his pubescent emotions. Thus, “The High Desert” works as literary hindsight, an ambitious chronicle of a Black kid’s sputtering attempts to crash a white party. According to some behaviorists, becoming white is a frequent fantasy among minorities, though most are too ashamed to admit it. Psychotherapist Sam Louie, who has analyzed many minority patients, says comments like “I wish I was white” are not uncommon. “You don’t hear the voices of those [minorities] who are subjugated to not only external racism, but their own internal self-critic,” Louie wrote in Psychology Today.

My own inner critic notwithstanding, I harbor few regrets about engaging white culture. As with Spooner, rock music helped preserve my sanity during a stressful adolescence. It also gave me a vocation: My knowledge of rock recordings like, say, Queen’s 1975 masterstroke “A Night at the Opera,” helped give me the range required to stand out in a crowded field of pop culture pundits.

James Spooner noticed that black punk rockers face unique acceptance issues. He asked around.

On the rare occasion when I do experience guilt over my wannabe-white teen fantasies, it’s usually accompanied by a laugh. Because when I listen to many of my favorite albums from the ‘70s — Aerosmith’s “Toys in the Attic,” Deep Purple’s “Burn,” Humble Pie’s “Smokin’” — I’m struck by how Black they sound. Here I thought I was rebelling against my race, when I was actually listening to the reverberations of my own culture, like an electric guitar feeding back its signal.

A similar revelation strikes Spooner in “The High Desert.” Noting that Elvis Presley never composed an original tune and that Led Zeppelin outright ”plagiarized” Black blues artists, the author triumphantly writes: “Rock ‘n’ roll is a Black American legacy. Punk music is Black music.”

Indeed, when one considers Black culture’s century-long sway over the world, it becomes clear that racial fantasizing runs both ways. Ever since the early 20th century, when the Jazz Age ushered in youth culture, a veritable white horde — Bix Beiderbecke, Elvis, the Rolling Stones, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Eminem, Post Malone and countless others — have strained every piston trying to talk, dress and perform with Black authenticity.

James Spooner and I weren’t the first guys to try and escape our skins. We certainly won’t be the last.

Britt is an award-winning writer and essayist.

A guide to the literary geography of Los Angeles: A comprehensive bookstore map, writers’ meetups, place histories, an author survey, essays and more.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.