How the West was won — and lost — by women: A new history revises the record

- Share via

On the Shelf

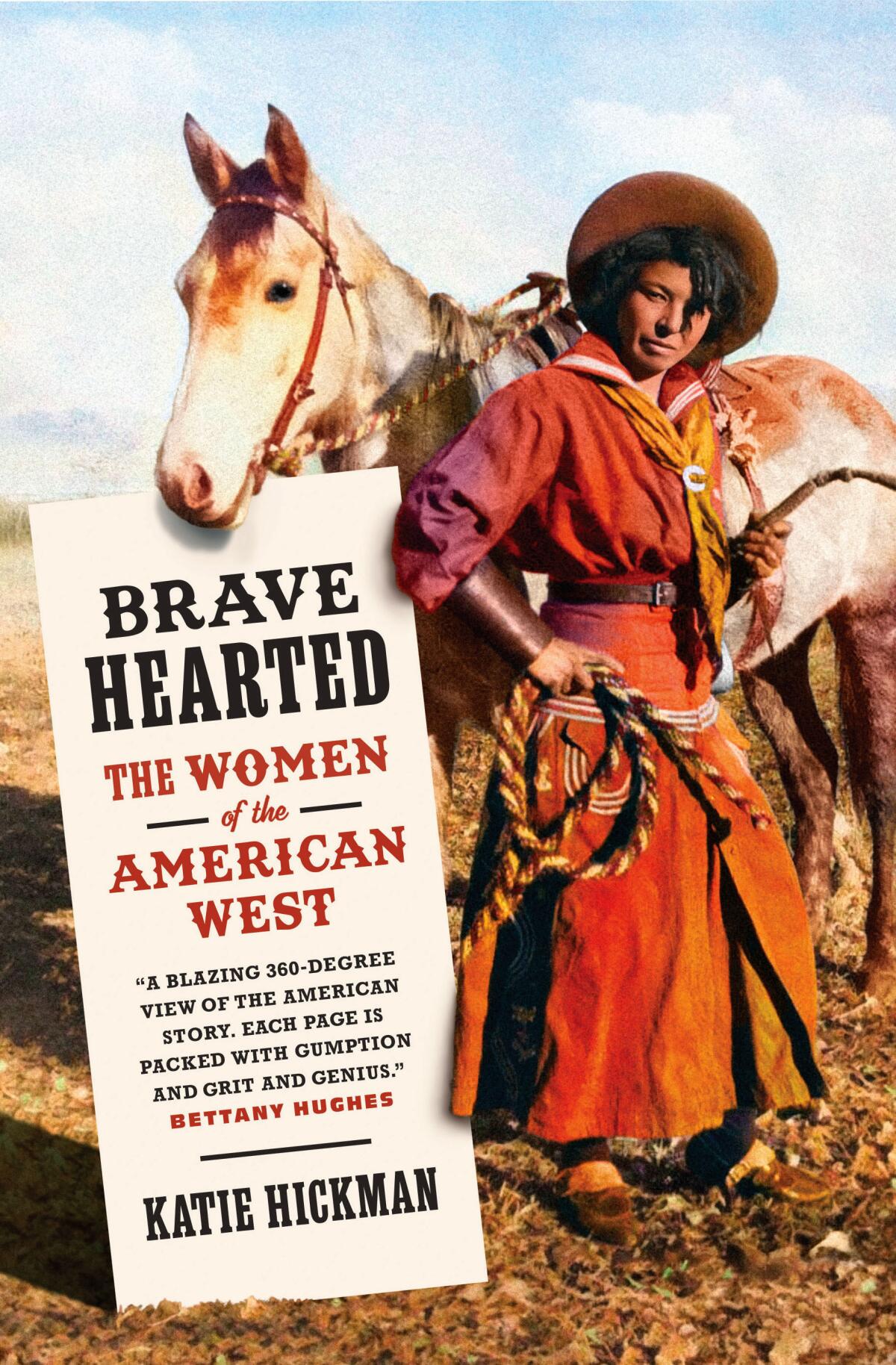

Brave Hearted: The Women of the American West

By Katie Hickman

Spiegel & Grau: 400 pages, $32

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

It’s hard to imagine a future in which the myth of the American West isn’t dominated by white men. It’s harder yet to imagine a moment when dismantling it is more important than it is today, as a kind of manifest destiny drives everything from pipeline permits to SpaceX moon flights. Even revisionist westerns that puncture the romance of settler colonialism (“Meek’s Cutoff,” “The Power of the Dog”) sideline Mexicans (the first cowboys), African Americans (who also rode West on wagon trains) and, most confoundingly, Native Americans.

Katie Hickman’s riveting new history, “Brave Hearted: The Women of the American West,” works to correct this imbalance by foregrounding the historical experiences of Western women — Black, white, Mexican, indigenous, mixed race and Chinese. It covers the period from 1836, when Presbyterian missionaries Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spaulding, the first “westering” women, set out with their husbands for Oregon country, to 1890, when the U.S. Census Bureau pronounced the frontier closed.

By then, half a billion dollars’ worth of gold had been hammered out of the earth, buffalo had been hunted to virtual extinction, Native children were being de-patriated in boarding schools and the massacre of entire Sioux families at Wounded Knee Creek in South Dakota marked the harrowing last gasp of “expansion.”

Hickman organizes her mosaic narrative by place (mines and forts, sites and territories, a half-baked utopian colony) and travel routes (the Oregon-California and Mormon trails; the cutoffs that sent some pour souls, like the famed Donner-Reed party, on catastrophic shortcuts).

The women she spotlights met various fates, few of them happy. Whitman, who left the day after marrying a fellow missionary she barely knew, was later killed by the people to whom they proselytized. Others succumbed to typhoid, cholera, exposure, starvation or sheer madness en route. One weary pioneer hopped down and refused to continue; when her husband finally left her behind, she overtook his party, circled back and set his wagon on fire.

Blaine Harden grew up on the story of the “Whitman Massacre” as a foundation myth of the Pacific Northwest. In “Murder at the Mission,” he debunks it.

Perhaps no woman in these pages inspires more awe than Biddy Mason, one of the first African American women to go West. Born into slavery, she was “given” as a wedding present to a Georgia plantation owner and his wife, who answered Brigham Young’s call to build his desert Zion in 1848. She joined a wagon train of 56 travelers, 34 of them enslaved. During the seven-month journey, Mason nursed her baby, tended to her two other children, served as a midwife and herded her enslavers’ livestock across plains and prairie, mountains and desert. When the family moved to California, in 1851, she secured her freedom after a harrowing legal battle.

For the record:

12:54 p.m. Oct. 25, 2022An earlier version of this review said Biddy Mason co-founded L.A.’s First Methodist Episcopal Church. She was a co-founder of L.A.’s First African Methodist Episcopal Church.

“It is almost impossible,” Hickman writes, “to imagine the courage” it took to do this, especially as an illiterate woman born without so much as a surname. Mason became a successful midwife, philanthropist and co-founder of L.A.’s First African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Like the enslaved, Chinese girls and women trafficked to San Francisco had no say in their journey. They were crammed onto ships starting in the 1860s, and some jumped to their deaths in the sea on learning their fates. (Just like the Texas educators who recently proposed calling slavery “involuntary relocation,” 19th century authorities dubbed Chinese sex trafficking “involuntary immigration.”)

Hickman quotes a heart-rending “agreement paper” for a prostitute named Yut Kim that spells out the terms of her labor, often addressing not the woman but her body: “If ... any man wishes to redeem her body, she shall make satisfactory arrangements with the mistress.”) Though some female Chinese immigrants found jobs in domestic labor or industry, the majority (72% by the 1870 census count) were sex workers. And some, like the famous madam Ah Toy, “took full advantage of the opportunities offered by the vice trade.”

Of course, plenty of women were Westerners long before outsiders appeared on their land. We meet Northern Paiute Sarah Winnemucca, whose grandfather, a tribal leader, considered white men his “brothers” until they began “killing everybody that came in their way” and set fire to the tribe’s winter supplies. Brulé Lakota member Red Cormorant Woman was one of hundreds of Native American women who married French fur traders. Her daughter Susan Bordeaux wrote about how local tribes lived in harmony with the traders, attending weekly dances together at Wyoming’s Fort Laramie, until the onset of the gold rush, which she called “a living avalanche sweeping before it all that the Indian prized.”

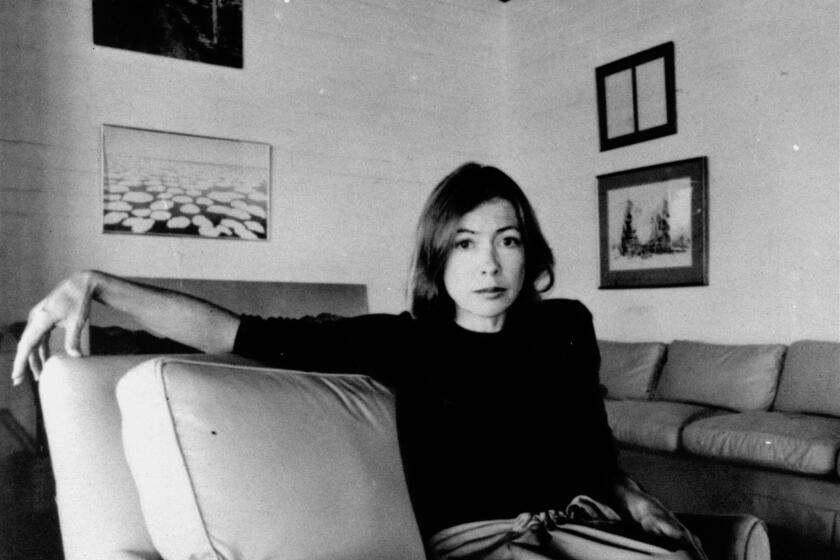

Joan Didion continues to resonate in California, even with a generation nothing like her.

Hickman’s writing is exquisite; her background as a novelist brings these women into dramatic relief. She has a keen eye for detail (a pioneer mother sews and packs shirts for her young son to wear West, “if he lives”). At the start of the California rush, she writes, “it must have seemed as though the entire [Feather] river ran with gold.” Stagecoach drivers were “rock stars of their generation. Famously ruthless, hairy, and hard-drinking, these kings of the road were both revered and feared by their passengers in equal measure.”

And yet, the logic of whom she includes is perplexing. Some of these women’s sagas are already well-documented, including that of celebrity captive Olive Oatman (whose biography I wrote in 2009, and whose experience as a Mohave adoptee was hardly typical). The Donner-Reed party debacle is so well worn it’s almost a punchline. With a clearer through-line, these stories might offer a stronger antidote to the calcified mythology that gave us “Gunsmoke” and “Yellowstone” or, failing that, a better sense of how they helped shape our national identity.

Even so, this is an irresistible crazy quilt of Western history. A meticulous scholar, Hickman draws on diaries and memoirs to immerse us in these women’s lives and offer important correctives. “Brave Hearted” is an alternate history of a frontier that was home for some and a fantasy for others — a liminal space that existed in fact and folklore long after the Census Bureau decided it was gone.

Mifflin is a professor at the City University of New York and the author of “Looking for Miss America.”

McMurtry, who died last week, made it his mission to redefine Texas as a crucible of modern conflicts. His early novels succeeded stunningly.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.