They posed as master and slave: The dramatic escape story behind a pathbreaking book

- Share via

On the Shelf

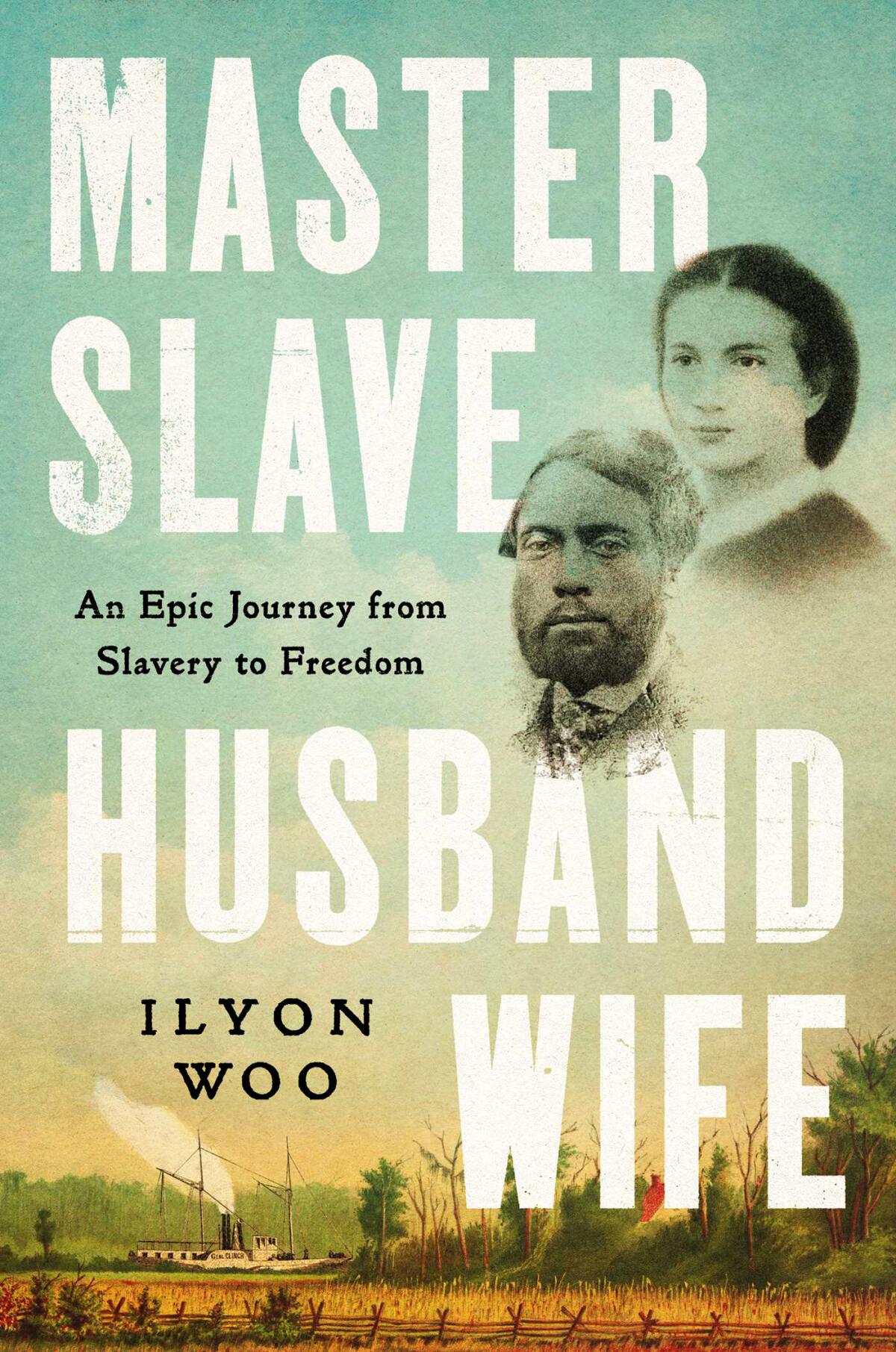

Master Slave Husband Wife: An Epic Journey from Slavery to Freedom

By Ilyon Woo

Simon & Schuster: 416 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Frederick Douglass has been a household name for more than 170 years. Harriet Tubman’s relentless bravery has her headed for enshrinement on the $20 bill. Sojourner Truth is an icon for her work as both an abolitionist and a feminist.

But beyond that trio of revered figures, the list of formerly enslaved Black people whose stories are remembered today is vanishingly small. Hollywood rescued Solomon Northup (“12 Years a Slave”) and Joseph Cinqué (“Amistad”) from relative oblivion. And now Ilyon Woo shines the spotlight on the saga of Ellen and William Craft in her riveting book, “Master Slave Husband Wife.”

Ellen, whose father was a slaver, was white enough to pass, but as a woman she could not easily travel unaccompanied in 1848. So this skilled seamstress created an outfit that enabled her to pose as a wealthy but ailing young man who needed constant tending to by his slave — William. After they slipped away from their plantations, this fiction enabled the Crafts to travel more than 1,000 miles over land and water from Georgia to the North. But instead of settling into the tranquility of freedom, they became nationally famous abolitionists, even as the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 put a target on their backs.

Imani Perry, a Princeton University professor and author of the personal history “South to America,” says it’s important that Americans learn to think beyond Douglass, Tubman and Truth. “The more stories we have of successful emancipation, the more complex our picture is of American history,” she says. “The Crafts’ story shows the ingenuity and intellectual sophistication required to escape the clutches of slavery. And the idea that they became abolitionists at great risk is hugely important, showing the idea of linked fate.”

This dramatic episode has not been completely lost; the Crafts told much of it themselves in a memoir, “Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom,” and there have been academic works and even a children’s book. But Woo’s version, while rigorously researched, aims to make their journey accessible for a wider audience.

The writer and Princeton scholar on “South to America,” her personal and historical tour of the region, and why so many liberals are wrong about it.

“Their story has long been cherished and studied in academia,” says Woo, who first read their book in graduate school at Columbia University. “But I felt there was a lot more there either that they couldn’t say or wouldn’t say and that I wanted to know.”

In a video interview from her home in Cambridge, Mass., Woo, who calls herself “a recovering academic,” said she consciously took a broader approach. “I wanted to write a book my parents could read and get something out of it.”

Woo initially struggled to find the balance between thoroughness and accessibility. “I’m normally hard on myself, but I felt pretty good about what I’d written and sent this chunk to my editor,” she recalls. “Time passes and I start worrying. Then she sends me a six-page document that begins with something like, ‘Clearly you’ve done a staggering amount of research.’”

The verdict was that the research was weighing down the narrative. “I had to start from scratch and let the story lead,” she says. “I read a lot of novels to see how they tell the story. It’s not like you read Colson Whitehead’s ‘Underground Railroad’ and he’s starting off with a description of how the railroad works. You’re following the characters and then learning about their world through osmosis, and that’s what I wanted.”

Perry considers the effort a success: “She’s an extraordinarily diligent researcher, who finds all kinds of material, but she also weaves a really engaging yarn.”

Even as a backlash brews over teaching America’s racist history, ‘Forget the Alamo’ and ‘How the Word Is Passed’ tell of the full, inglorious past,

That distinction resonates with Peggy Trotter Dammond Preacely, a writer and activist who was jailed for registering Black voters before becoming a Freedom Rider and joining the March on Washington. Preacely attributes some of her passion for the cause to the Crafts, who were her great-great-grandparents.

“My mother taught my brother and me about them,” she says, adding that so much of Black history was only passed down orally because literacy was illegal for slaves. “What’s so wonderful about what Ilyon has done is that she has created a visceral experience. It’s not a dry [academic] book. It’s not a novel, but it reads like one.”

(Preacely has also been consulting on a feature film about the Crafts that isn’t connected to the book; Woo says there may be a second Craft project in development.)

The author has a theory about why this particular story has been mostly overlooked; it “resists closure and an easy ending,” Woo says, and it “implicates the entire nation.” While the Crafts had allies in Philadelphia and Boston who were willing to risk everything for them, there were plenty of Northerners “invested in this criminal system who are committed to bringing the Crafts back to slavery.”

This includes legendary statesmen like Daniel Webster, whose desire to preserve the Union at all costs led him to promote the Fugitive Slave Act as part of the Compromise of 1850 and essentially argue, Woo notes, that there are very fine people on both sides.

Nikole Hannah-Jones talks about power, privilege and ‘The 1619 Project’ in advance of her L.A. Times Book Club visit.

Woo also zooms out to give us a sense of America in that era, starting with 1848, a year in which democratic revolutions erupted abroad while a slave owner occupied the White House (James Polk). She strives not to judge anyone, whether it’s Webster or Robert Collins, the husband of Ellen’s owner (and half-sister). But her fullest portraits of supporting players are reserved for members of the various factions of the abolitionist movement, both Black and white — including William Still, William Wells Brown and Robert Purvis.

“It’s tempting to focus on individual heroes, but they exist in a community and that’s what I wanted to evoke,” Woo says, holding up the book to show that it opens with photos of “this multiracial army of people fighting alongside the Crafts.”

It’s that broader context, says Perry, that makes Woo’s contribution as crucial as the Crafts’ original memoir, providing “a more vivid and complex portrait … that gives us a greater grace with our own political moment.”

In its scope, “Master Slave Husband Wife” offers a sense that there are far more stories left untold than those we have been taught in school. “For every Douglass, Tubman and Craft,” says Woo, “there are people we don’t know who succeeded or tragedies about people whose escape failed.”

But the story of the Crafts — not just their initial escape but their activism and its consequences — is particularly compelling as a lesson for a nation still struggling to come to terms with the implications of its horrific past. “The Crafts’ story makes America look both great and terrible,” Woo says. “It shows us what can go horribly wrong but also what can happen when we do come together.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.