How to survive a family cult in the Angeles National Forest, according to a memoir

- Share via

Review

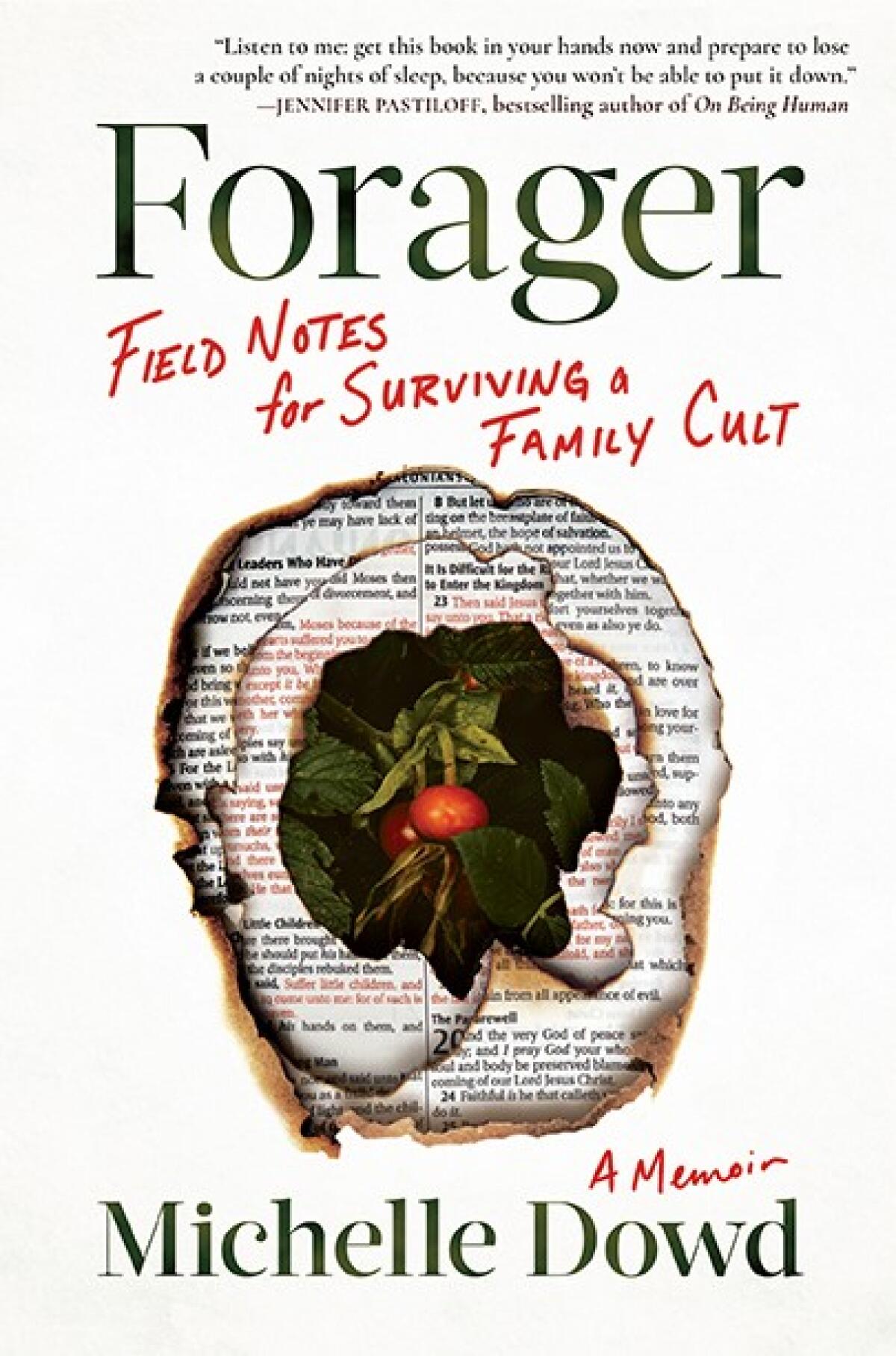

'Forager: Field Notes for Surviving a Family Cult: A Memoir'

By Michelle Dowd

Algonquin: 288 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

To get a sense of the strangeness — and often horror — of Michelle Dowd’s adolescence, you can consult the words she capitalizes in her new memoir, “Forager.” She’s a member of a family cult called the Field, which is committed to saving Outsiders. To do this, she goes on Trips that include tent-revival stops. In this manner, she and her family will be prepared “should the Apocalypse rain down upon us, and the blood rise to the horses’ bridles.”

In 1976, when Dowd was 7, her family moved to a 16-acre patch of land in the Angeles National Forest leased by her grandfather, who claimed to be a Christian prophet who would live to be 500. (Spoiler: He doesn’t.) At the Field’s main compound in Arcadia, Dowd’s father and grandfather prepared young men for the end days through Army-style training and rounds of scripture quizzes called Bible Basketball. Girls, meanwhile, were trained in forest survival skills, which included identifying native flora and fending off bears. Her mother is a skilled naturalist, and her axioms repeat themselves in Dowd’s head throughout the book: “Don’t be afraid. Be competent.” “Survive fear. Survive with faith.”

Following the new double-dipping template of memoir and documentary, Pamela Anderson finally tells her own story with remarkable matter-of-factness.

Dowd signals some peculiarities of her preteen existence early on. Girls’ day clothes are repurposed pillowcases; on Trips, she wears a full-body robe called a djellaba “to keep men from looking at our bodies.” On one Trip, the RV catches fire, killing a dog inside, an incident the Field so casually chalks up to God’s will that Dowd’s sister draws a picture of it — which the driver frames. (“It will hang in her house for many years, and I will look at it every time I babysit her children.”) But Dowd purposely keeps the storytelling at a low boil, evoking the way that this severely antisocial existence felt for years like something normal.

Until, inevitably, it stopped feeling that way. Dowd’s change is in part a function of simple curiosity. She was drilled constantly on Bible verses, but as she neared adolescence she began to notice contradictions in the Bible and hypocrisies in the proselytizers. She logs them, along with other observations, in a Sears catalog, the sole secular book she possesses; she hides it under her mattress.

But the constraints and abuses are as physical as they are psychological, and by its midpoint “Forager” fully becomes the trauma memoir only hinted at in the opening pages. The structure of the Field is patriarchal and aggressive, with women expected to be chaste and subservient. When uncles arrive at the Field, she identifies which is which “from the way he twists my arm, yanks my hair, or rubs his whiskers along my inner thighs, along the softest places of my body.”

Barely a teenager, Dowd has been denied the language and socialization to name this as a violation, which makes the story’s impact on the page all the more brutal. All she has is survivalist language: “I don’t know what’s appropriate for humans. When it comes to humans, I know only the identifying characteristics of apex predators and how to appease them.”

‘Women Talking’ novelist Miriam Toews discusses what Mennonites think of the Oscar-nominated film and what she thinks of Sarah Polley’s use of the Monkees.

“Forager” contains more than a faint echo of Tara Westover’s blockbuster 2018 memoir, “Educated,” which recalls a childhood in a separatist family before Westover breaks free to become a Cambridge-minted PhD. Dowd, too, broke away: She connected with former Field members (“Quitters”), was excommunicated, attended college and, of course, wrote this book. But the arc of “Forager” isn’t nearly as triumphant. It’s not, like Westover’s, a tale of seclusion replaced with secularism. Dowd shares only enough information about her post-Field life to suggest that her escape in 1986 was successful — and that, indeed, “escape” is the correct word for what happened.

Because the book is so focused on the 10 years during which she was fully a member of the Field, an atmosphere of ambivalence hangs over the narrative. It was unquestionably a time of abuse and violation, made all the worse because God became a curtain for everybody to hide behind. “Silence is conspiracy, just as it is consent,” she writes. “In our family, we turn quiet when we are lost, and we have been trained to look up, not to one another.”

Yet Dowd’s story surfaces a bitter irony. The wisdom and resolve she required to leave the Field — her survival skills — were taught through lessons designed to keep her there. The book is stronger in some ways for leaving that irony unspoken; it’s a prompt to the reader to consider our own adolescences. The risk of Dowd’s approach is that it neglects those who didn’t or couldn’t leave — who lacked Dowd’s resolve, intelligence or sheer luck. She notes that the Field still exists but is now a “radically different organization.” For better or worse? Knowing how and why it shifted might offer some lessons for what makes family cults — and what might stop them.

“Hollywood Park,” a new memoir from the frontman for the Airborne Toxic Event, recounts his childhood in L.A.’s Synanon cult — and his recovery.

Without that big-picture perspective, Dowd leaves the impression she’s grateful for the knowledge she’s gained, though she wishes she’d acquired it differently. She’s left the Field but is “still my mother’s daughter.”

Every chapter in “Forager” opens with a brief description of a native plant she knew well in the forest: pine cones, succulents, berries, weeds, lichen. Though short, they do some serious metaphorical labor, trained on matters of hardiness and sustenance. The California black oak, for instance, is “strong, sturdy, and self-sufficient” — and, by extension, so is Dowd. She delivers this information dispassionately but with a certain sense of pride, the suggestion being that she thrives just as these plants do, that her traits and nature’s are intertwined and that her knowledge of both is a blessing. Self-sufficiency is a virtue. But it’s no way to run a society.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.