P-22 speaks! A lonely cougar narrates a new novel about the feral side of L.A.

- Share via

Review

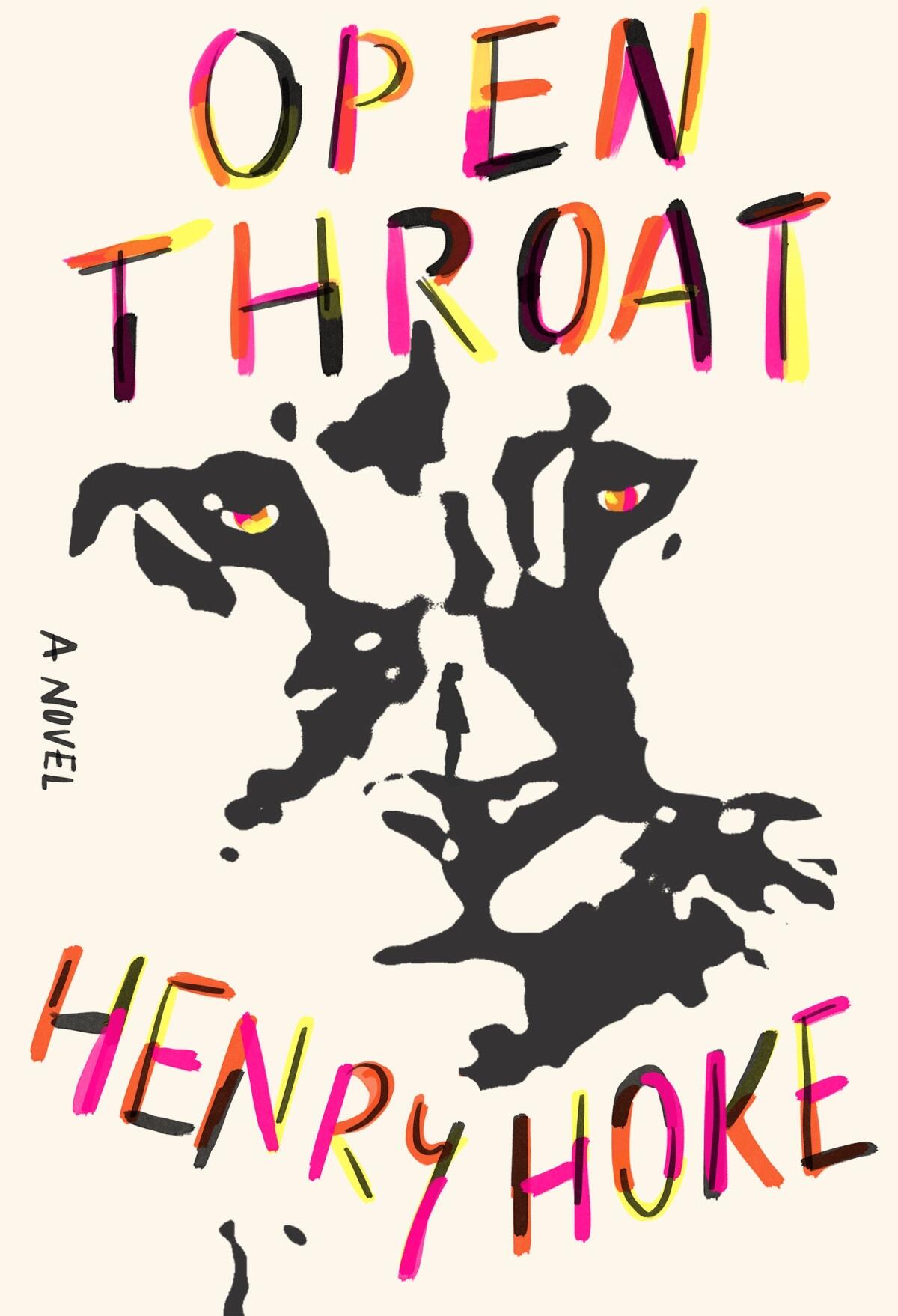

Open Throat

By Henry Hoke

MCD: 176 pages, $25

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

When the venerable mountain lion P-22 died last December — euthanized after a car accident that was at once shocking and all too likely for a creature of the city — he accomplished what all true icons do. He became a magnet for metaphors. The longtime habitué of Griffith Park was a symbol of a ferality lurking under L.A.’s sheen. He was an avatar of rugged individualism. He exemplified celebrity in a city fueled by it, represented border-crossing in a place that knows it well, provided an image of persistence in an environment that sometimes seems determined to undermine it.

In his fifth book, “Open Throat,” Henry Hoke makes a P-22-esque puma his narrator, and from the beginning it is clear the author is mainly on Team Ferality. (First line: “I’ve never eaten a person but today I might.”) Fittingly for a creature with pressing hunger and no time for chit-chat, the big cat’s delivery is terse and prose-poem-like. That makes for a propulsive, one-sitting read, if also a somber one. The creature’s observations about “ellay” tend toward the melancholy — and who can blame him? The natural world he needs to thrive in is disappearing, sometimes flooding and sometimes burning. He hears the word “scarcity” and thinks “scare city.”

Photos of the mountain lion P-22, who lived in L.A. and became the face of an international campaign to save California’s threatened puma population.

Constructed out of loose, brisk chapters with little punctuation or capitalization — the cat is plainly an alumnus of the Archy and Mehitabel school of talking-animal prose — the plot is effectively a series of trials. He despairs of finding prey. The dry climate, and the wildfires that result, leave him scared and trapped. He circulates around a homeless camp and plots his vengeance against some of the cruelty he witnesses there. A girl takes him for a time, tells him about Disneyland. He dreams of riding down Splash Mountain, watching the fireworks and claiming his spot at the happiest place on Earth.

Which is to say that Hoke means to intertwine the cat’s fate and concerns with those of Angelenos. Apex predators — they’re just like us! Of course, every animal story from “The Metamorphosis” to “Charlotte’s Web” strives to do something like that, exposing our humanity by recontextualizing it in the animal world. Here, the cat feels frightened and isolated from living so close to threat. In the process, Hoke suggests that our lives are isolated and precarious too. (“I’m the secret member of town,” as he puts it, but then aren’t we all?)

So even though the narrator is a very cat-like cat, feasting on bats and rattlesnakes and the occasional deer, some human traits creep in. He ponders finding a therapist — the people he overhears chatting about it on their phones make the idea sound so interesting — and pursues a flirtation with another male cat over some carrion. “When you meet a big cat who will share a kill you can’t let go of him easily,” he opines. It’s love, of a kind.

The 14 most essential L.A. poems or poetry collections, including those by Wanda Coleman, Robin Coste Lewis, Sesshu Foster, Bukowski, Brecht and more.

It’s easy to appreciate the playful-yet-serious dynamic of Hoke’s novel on its face, and he’s entering a rich talking-animal tradition, encompassing not just fairy tales and children’s literature but political allegory (“Animal Farm”) and the soberest of memoirs (“Maus”). But even as a one-sitting read, “Open Throat” can feel a little over-long. A cat, even a wily one, only has so much to say about the state of humanity. So the narrative sometimes drifts into simplistic, wry observations about money (“I jump down and pick up the paper in my teeth / I try to taste its importance / nothing”) and climate (“they’re afraid of the dryness like I’m afraid of the dryness”).

The lowercase, clipped narrative tone is meant to project urgency and a distinct style. At times, though, Hoke’s P-22 manqué feels less like a cat and more like a too-earnest Instapoet (“no one sees me unless I want them to”; “it’s nice to be fed and praised at the same time”; “I don’t trust screens to tell me who I am”).

Nevertheless, an overall sense of peril — for the cat, and for us — comes blazing through. The story of Hoke’s narrator, much like P-22’s, is one of constantly avoiding tragedy, often by a hair’s breadth. That’s another thing animal stories are designed to do: remind us of our own lives’ brevity. Without spoiling the story, it’s perhaps enough to say that the climax of “Open Throat” is a very L.A. one, with spotlights and drama. But it’s also a universal one. We all have to make compromises for the sake of getting by; a big cat just has sharp teeth and claws to apply to the task. “It’s a terrible choice but I’m making it,” he laments at one point. “Just like a person.”

“Discovering Griffith Park,” a history-rich guidebook by Casey Schreiner, gives one of the country’s largest, greatest city parks its due.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.