Page to Screen

'American Fiction,' adapted from 'Erasure' by Percival Everett

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

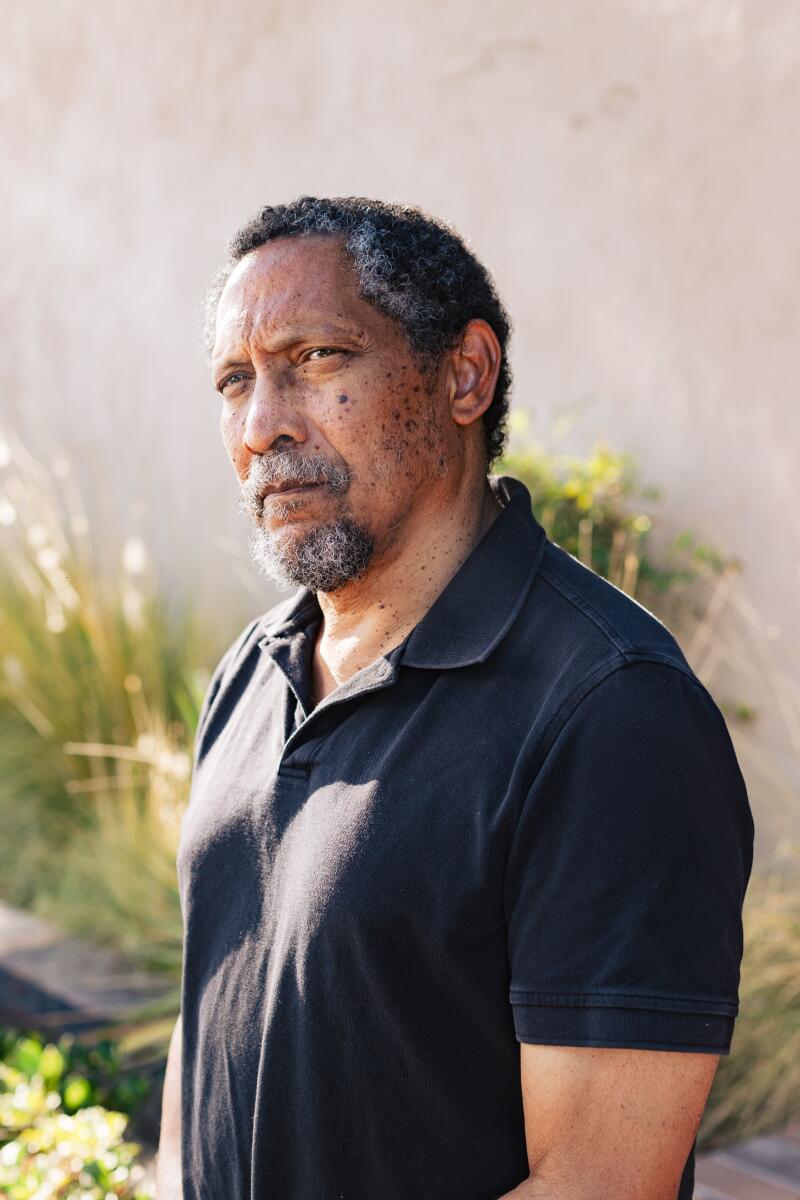

In his award-winning 2021 novel “The Trees,” Percival Everett conjures the family who led the lynching of Emmett Till. Its members are inbred and illiterate, with names like “Junior Junior,” in a parodic reversal of white supremacists’ grotesque imaginings of Black life. It gets wilder; there’s an undead revenge plot. As with much of Everett’s writing, its forceful, unapologetic approach makes it hard to forget.

With the movie “American Fiction,” screenwriter-director Cord Jefferson (a writer on “Watchmen”) adapts Everett’s cutting satire “Erasure” as his feature debut, out this week. Where the 2001 novel was scathing in its look at white racial attitudes, “American Fiction” pulls punches, softening the book’s critique into something widely palatable. The press notes quote Jefferson’s desire to make the film a “big tent” and the producers’ intention that it be “universal.” Indeed, it’s a feel-good movie — albeit somewhat muddled and porous — with strong contributions from cast and crew. But if you’re a fan of Everett’s unsparing truth-telling, you’re likely to be disappointed by this sweetened version of his polemic.

Author and USC professor Percival Everett joins the Los Angeles Times Book Club on Nov. 16 to discuss “Dr. No” at the Autry Museum.

In “Erasure,” Everett picked up other themes from his expansive body of work: family, mindless consumption, uses and abuses of art. In the story, experimental author Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, incensed by the kind of Black stories that sell, formulates a fraud to pay for care of his declining mom. Using the alias Stagg R. Leigh, Monk submits a novella that traffics in ‘hood cliches (original title: “My Pafology”). The publisher fawns; the public adores it; an awards committee takes notice. By embracing sensationalist images of criminality and ignorance, Monk has at last written something “Black” enough to be read as authentic.

“American Fiction” prioritizes the story of Monk’s family, moving it from Washington, D.C., to the Boston area. Jeffrey Wright stars as Monk. While the book parceled out his childhood memories to reveal the Ellisons’ history, the film summarily delivers a neater version through Lisa, Monk’s ob-gyn sister (Tracee Ellis Ross). Here too, Jefferson’s script is gentler; she’s no longer assassinated by an anti-abortion nutbar. The dynamic between their mother (the legendary Leslie Uggams) and her live-in housekeeper (Myra Lucretia Taylor) is genial rather than strained by class tension, turning one formerly climactic scene of crisis and chaos into a Hallmark moment.

Jefferson improves on Everett’s portrayal of the Ellisons in one way: The book didn’t do justice to Monk’s brother, fresh out of the closet and living a second adolescence. The film allows him full humanity with a more nuanced role — and a glorious performance by Sterling K. Brown.

The story’s central issue was a hot topic in 2001, following the commercial success of “street” books like Sapphire’s 1996 “Push” — adapted into the 2009 film “Precious” — and Sister Souljah’s hit “The Coldest Winter Ever” (1999). Some Black intellectuals indicted these stories for feeding white hunger for ugly pictures of Black life. “Erasure” came out within months of Spike Lee’s film “Bamboozled” (2000), which told a similar story with TV as its subject: A frustrated producer creates a show of literal blackface minstrelsy, and the network and audience devour it without irony. The film flopped at the box office, but it’s become a classic in the years since for its undeniable courage. That movie looms over this one.

When it came time to adapt ‘Eileen’ into an Anne Hathaway-starring film, the ideal writing team was its author Ottessa Moshfegh and her husband, Luke Goebel.

In the framing device of “Erasure,” the novel was Monk’s journal, and as such it was highly erudite and often arcane. Few will miss its more obscure passages here, but “Erasure” also offered “Stagg’s” text in its entirety, painting his protagonist Van Go as a repulsive serial rapist. This is the figure Stagg’s many enthusiasts hold up as a prime example of a real and true Black character, so the racism of their reaction is hard to miss.

The film puts us in a more ambiguous place. All we learn of his story is a scene showing Van Go’s anguished murder of his negligent father. The characters are stereotypes, but without seeing more of Van Go, we’re left unsure of how to interpret the book’s reception. Is the public signing onto a depiction of Black men as serial predators, or as hapless victims of social decay? Is the racism flagrant and virulent, or insidious and patronizing?

The context surrounding Everett’s story has evolved in 20 years, but Jefferson shies away from a meaningful reworking, instead making noncommittal gestures in several directions. Live TV figured big in the book, yet here we see little of online culture, which could have offered rich material. Publishing has changed as well: For one thing, street lit has become its own thriving genre. While it’s been a boon for Black-owned indie publishers and bookstores, the presses are now being subsumed by the Big Five in a reflection of industry-wide shifts. Jefferson’s screenplay doesn’t take into account how all of this might have affected Stagg’s rollout.

BIPOC publishing professionals have worked hard to give voice to more diverse Black stories. Nodding to this, John Ortiz is a highlight as Monk’s agent — no longer just sympathetic, he has some skin in the game. The industry has a long way to go, but if Monk’s tossed-off manuscript were to shoot past the ranks of genre standard-bearers and be anointed by the mainstream establishment, a release this year would be competing with hits by James McBride, Zadie Smith, Jamel Brinkley, Victor LaValle, Brandon Taylor, Colson Whitehead, Bryan Washington and Teju Cole, none writing about thug life or sharecropping — and none recognized by this film.

Victor LaValle’s novel ‘Lone Women’ reinvents the western, adding horror and a Black woman pioneer protagonist — with help from the women in his own life.

In any event, the scenario is unlikely; as a more successful Black author confirms in “American Fiction,” Stagg’s book isn’t good. She points out that Monk doesn’t see the Black accomplishments already there. Watching the film, though, neither do we.

Jefferson adds one crucial element missing from the book, bringing Monk face to face with that author (Issa Rae). Monk has resented her from afar for writing he believes to be exploitative, and now she has a chance to respond. She points out his snobbery, and suggests that he’s devaluing other perspectives in a way that smacks of unchecked privilege. It’s a moment of genuine conflict that could’ve led to deeper engagement, but ends precipitously.

Percival Everett’s 2001 novel “Erasure” had more bite than the new film adaptation, “American Fiction.” (Graywolf Press / Wesley Lapointe/Los Angeles Times)

Later in the movie, we glimpse another promising direction Jefferson might have taken, which could have produced a more logical film. Monk-as-Stagg meets with a hot Hollywood director (Adam Brody) who wants to adapt his book for the screen (in “Erasure,” it’s a crusty producer). He tells Monk he’s working on a movie called “Plantation Annihilation,” perhaps a reference to “Watchmen” and similar genre-fications of U.S. racial trauma (“Lovecraft Country,” “Antebellum” etc.). A subsequent conversation between the men implicates films about police killings in Black death spectacle, but stops short of actual critique — unless the message is something like, “lighten up and cash in.”

Where “Erasure” seethed at injustice, the anachronistic “American Fiction” is most effective at skewering its protagonist. It’s Jefferson’s prerogative to focus his film on tender family moments. But I hope his next outing involves an original screenplay — or material that better suits his goals.

Johnson writes The Times’ Page to Screen column. She lives in Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.