- Share via

On the Shelf

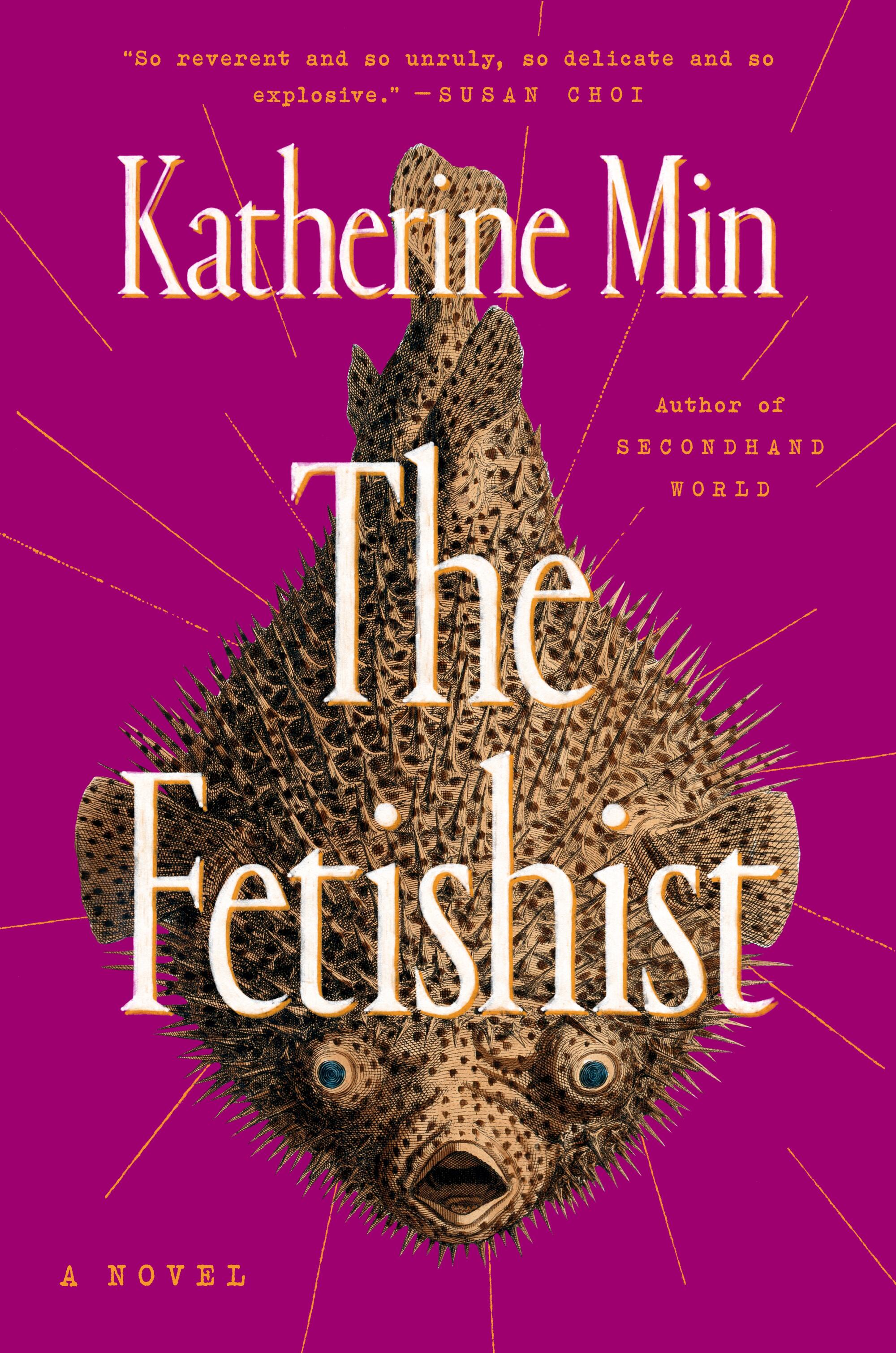

The Fetishist

By Katherine Min

G.P. Putnam’s Sons: 304 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

This is the story of a fabulous book that almost never was. A lush and vicious novel with the pacing and urgency of a thriller, “The Fetishist” revolves around desire and revenge, focusing on the abduction of a classical musician with a history of predatory behavior by the punk-rocker daughter of his former paramour, who had killed herself after being spurned by him. It’s the second novel by Katherine Min and it arrives nearly four years after her death.

Min was a connector, a writer and professor who built communities through residencies, conferences and classrooms. This explains why her posthumous publication will be marked by a substantial book tour (including a Los Angeles stop Jan. 23) shepherded by a legion of friends and former students and helmed by her daughter, Kayla Min Andrews, who recovered the file that became “The Fetishist.”

While I was neither Min’s peer nor her student, I was a devoted reader of her work. In August 2006, I met Min at the MacDowell residency shortly before the publication of her debut novel, “Secondhand World,” at Knopf, where I was then an editorial assistant. Her enthusiastic and unguarded demeanor was refreshing, and I loved her intense but tender novel. Her reading at the KGB Bar in Manhattan that fall struck me as an auspicious launch. Sadly, it was her last book tour.

Why did Penguin decide to reissue a memoir and a novel by Harry Crews, a dead white Southern writer? His influence — and his truths — run deep.

“Secondhand World” was a coming-of-age novel, set in upstate New York in the 1970s, with autobiographical elements of the immigrant experience. But it was also a propulsive, remarkably literary work that burned with complicated longing. Knopf senior editor Victoria Wilson bought the novel for “the virtue and power of its writing.”

In the early aughts, books that captured the Korean American experience were not so prevalent, much less wildly feted (this was before Min Jin Lee’s “Pachinko” and Michelle Zauner’s “Crying in H Mart”). One fan of “Secondhand World,” Putnam publisher Sally Kim, kept it on a small section of her bookshelf devoted to (the precious few) Korean American novels. She would end up editing “The Fetishist,” but at the time, Min’s debut didn’t find a wide audience.

Speaking over the phone 18 years later, Wilson remembers Min’s intensity, commitment and seemingly limitless promise. Knopf had a crowded list that fall — the season of “The Emperor’s Children,” “Half of a Yellow Sun” and other breakthroughs — but Wilson and others worked hard to bring attention to Min. Publicist Tessa Shanks recalls “cooking up a scheme” with Min to stretch the touring budget toward as many cities as possible. “I believe Vicky was a little taken aback by our excitement for what was a relatively small book,” says Shanks.

“Secondhand World” created a path for Min to become a tenured professor at University of North Carolina in Asheville. It received praise and a nomination for a PEN/Bingham award. Min continued to write at artists’ residencies, working on what would become “The Fetishist.” But when she was diagnosed with Stage 4 breast cancer in early 2014, she shut the door on fiction.

Instead, Min shifted to nonfiction. “It was like a switch was pulled,” remembers her friend, writer Marie Myung-Ok Lee. Min “felt an urgent need to write essays, particularly on her new perspective on life having cancer.” While Lee is pleased by the publication of “The Fetishist,” she also hopes these essays will be published as a collection. “Even through all her treatments and their side effects … she was always writing. That was her way of being.”

Cai Emmons discusses being diagnosed with ALS shortly after finishing the surrealist California novel “Unleashed,” one of two novels out this September.

Min brought the same commitment to this work as to her fiction. “She wasn’t willing to compromise the urgency at their core in order to receive faint praise or recognition,” remembers another friend, writer and translator Geoffrey Brock. When a “well-known journal” proposed “some wrongheaded cuts,” she withdrew the piece and sent it to Brock at the Arkansas International, where he ran it intact. (“An orange I can manage,” runs the darkly funny opening. “This sumo orange, with its pocky skin and bulbous shnozz.”)

“If there was any silver lining to the way she went out,” says Brock, “it was that she did so with that kind of confidence … intact, despite those publishing realities that must have made it hard to maintain.”

The year Min died, her family created a fellowship in her name at MacDowell, where she was an artist-in-residence eight times, which would provide opportunities for Asian American writers. This did much to preserve her memory, but what about her unpublished work?

Initially, the family hoped Min’s essays could be published as a collection. To that end, Kayla Min Andrews approached her mother’s friend, the writer Cathy Park Hong. Hong connected Andrews with P.J. Mark, Hong’s literary agent.

Reached by email, Mark recalls thinking the collection could work — if introduced and properly framed by her contemporaries. But he asked Andrews about any additional material. She mentioned that Min had shared individual chapters from her novel-in-progress before her diagnosis. “I had a sense of the characters,” Andrews recalls of her mother’s manuscript. “I had some sense of the plot, but I had never read the whole draft in order.”

After talking to Mark, Andrews went back to her mother’s laptop which she now used as her own. The files were there — a complete version of the novel, including notes on elements to add or check. It was dated from the end of February 2014, just before Min’s diagnosis. For an ostensibly unfinished manuscript, it was remarkably polished.

In ‘Yellowface,’ R. F. Kuang has traded in fantasy fiction for a wild satire on literary scandals over appropriation and plagiarism. How and why she did it.

“The Fetishist” was Mark’s introduction to her fiction. “I found it hilarious and moving and so contemporary, which surprised me as it had been written some years ago.” Predating #MeToo, the novel directly addresses a generational shift away from patriarchal resignation. In the novel, Min pursues the idea of matching violence with violence, but also explores the gray area of reconciliation and rehabilitation. To Mark, “it felt like a timeless comic fable of revenge and also a modern cultural critique. And even though I had no attachment to Katherine, I felt an urgent responsibility for the book and to honor her legacy, which was an unexpected feeling I couldn’t explain.”

Mark had an ideal editor in mind: Sally J. Kim. He offered her an exclusive submission.

Reading the manuscript alongside the rest of Min’s work felt, to Kim, like having a conversation with Min in her head over the course of one intense week. Kim thought, “What would she think of our world today, which has changed so much since her passing in 2019 — the pandemic, George Floyd, AAPI hate? I wished I could talk to her about so many things. I still do.”

During the editing process, Andrews, herself a writer, stepped in eagerly on her mother’s behalf, working hand in hand with Kim to expand scenes and smooth out loose ends. “There were moments and lines,” Kim says, “that startled me in how prescient Katherine had been about Asian American identity, objectification, desire and how all these things often get tangled up.”

For all of Andrews’ hard work, “The Fetishist” ultimately owes its publication not just to those with a personal stake in her life but to the people who found immense value in her work.

Following the Atlanta shootings, books by AAPI authors including George Takei, Nam Le, Steph Cha and Maxine Hong Kingston offer essential perspectives

“I was never lucky enough to have met Katherine,” says Kim, “but I have such a strong sense of her wisdom, her warmth, her wit, her ferocity. It’s driven me to do everything I can for this book. I’ve been in book publishing for almost 30 years, and in many ways Katherine’s struggles as an emerging Asian American writer run parallel to my own, and there are times that I mourn that fact, for both of us. But it also feels as though I’ve worked my whole career to be in the position to publish this book in the fulsome way that it deserves. This book is a celebration.”

LeBlanc is a critic and board member of the National Book Critics Circle. Her Substack is laurenleblanc.substack.com.

A celebration of Katherine Min’s “The Fetishist” will take place at Village Well Books & Coffee in Culver City on Jan. 23 at 6 p.m.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.